< Previous

'A very distinct acquistion':

The Dale Cinema

By Stephen Best

The first article in a series on Sneinton cinemas

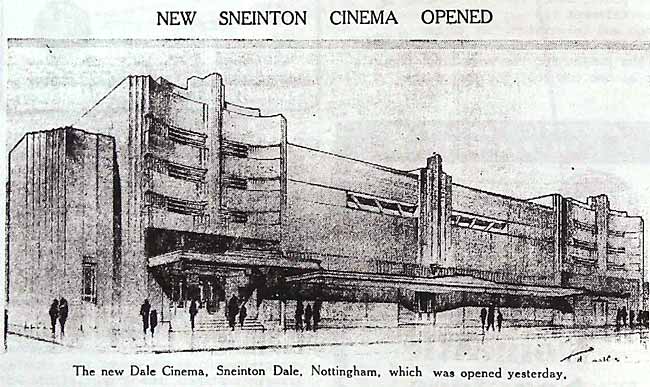

On Boxing Day 1932 there opened in Sneinton a building which, according to the local press, gave 'every indication of being a successful and appreciated addition to the city's houses of entertainment.'

The Dale Cinema was launched with much optimism and a good deal of style, and proprietors and patrons alike would no doubt have been dismayed and astonished had they been told then that its active career as a cinema would last only a little over twenty-four years. Built on 'a valuable site at the junction of Sneinton Dale and Hardstaff Road', the new cinema was not only a boost for Sneinton's morale in the dark days of the slump, but also a distinct contribution towards the economy of Sneinton in particular and Nottingham in general. As the chairman of directors stressed at its opening, almost all the labour used in the building of the cinema was obtained in Sneinton, and four-fifths of the money spent on the construction and equipping of the Dale was 'British and Nottingham money', with numerous local firms carrying out the work. At a time when local unemployment figures were approaching 18,000 (over 15% of Nottingham's workforce), this emphasis on the involvement of local employers and local workers must have had considerable relevance for Sneinton people.

The cinema's architect, Mr. Alfred J. Thraves of Nottingham, had plenty of experience in designing places of entertainment, having already been responsible for the New Empress on St. Ann's Well Road, the Majestic at Mapperley and the Tudor, West Bridgford. In addition to designing these local cinemas Mr. Thraves had remodelled the Plaza cinema, Trent Bridge, and had been the architect of that other magnet for Nottingham pleasure-seekers, the Palais-de-Danse. Later in the 1930s he was to be the designer of such imposing cinemas as the Astoria,

Lenton Abbey and the Forum, Aspley Lane. In those pre-television days of 1932 Mr. Thraves felt able to design the Dale Cinema with a capacity of 1,500. Clearly its directors were expecting a clientele that went beyond the boundaries of Sneinton, as the provision of a free car park for patrons indicated. 'This amenity' remarked the press 'will no doubt prove useful to picture-goers in the Mapperley and Colwick district. They now have a first-class cinema close at hand, with the advantages of being able to leave their cars and motor home in comfort.'

What other facilities were the directors offering to this latter-day carriage trade? Mr. Thraves had, according to the Nottingham Guardian, conceived the Dale Cinema on the most modern lines 'without embarking on fantastic design.' The entrance was described as 'a notable part of the building, carried out, as it is, in solid polished terrazio, inlaid with golden mosaic.' Thought was also given to those who, underestimating the popularity of the new cinema, might arrive too late to get even into its distinguished circular foyer. 'Right along the side of the cinema is a glass canopy, for the convenience of queueing. When the house is full, everybody outside will be able to wait under cover.' While waiting to become one of the fifteen hundred in the audience, the queueing patron would have been able to admire the striking lines of the Dale. Darkness would have been no obstacle to architectural appreciation, as both floodlighting and neon lighting were installed 'on the latest plan'. Revealed by the lights, Mr. Thraves's exterior design was there for all to see, in red sandstock brick with variously coloured facings. Certainly the Dale Cinema must have been the most modern-looking building in Sneinton in 1932.

Once inside the cinema the picture-goer would have noticed that there was no balcony in the auditorium. 'For this reason alone', explained the Nottingham Guardian, 'the acoustic properties of the building are perfect.' In accommodating his audience the architect had striven for cosiness 'achieved without cramping design'. The screen was placed behind a wide stage and, said the paper, 'in order to ensure that patrons in every part of the cinema shall have perfect vision, several rows of seats have been sacrificed'. This feature was doubtless greatly appreciated by film fans accustomed to emerging from some older Nottingham cinemas with necks stiff from gazing up at the screen from a cramped front row. The safety and comfort of paying customers were indeed given maximum consideration, with the latest fire-proofing system then available, and with more exits and lavatories than were required by the local authority. One feature of the Dale that patrons were unlikely to see in operation was the vacuumcleaning installation, 'so arranged that the building can be thoroughly 'spring-cleaned' in a few hours'. The Dale Cinema was of course equipped for sound from the outset, with 'the latest type of Western-Electric talking apparatus'. Sound engineers had in fact been involved in planning a 'perfect auditorium' with the architects before even the foundations had been laid.

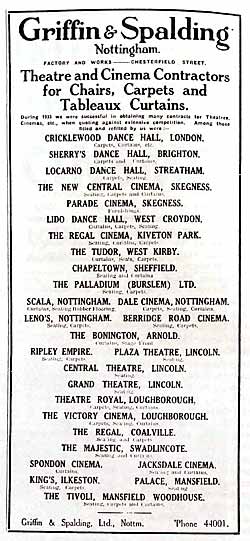

Among the local firms collaborating in the building and fitting out of the Dale were several names still familiar in Nottingham today. Some of them couched their advertisements in words which showed that cinema work was a line worth specialising in between the wars. The actual builders of the cinema were W. & F. Che11 of West Bridgford, who also carried out the joinery and woodwork. Their advert bore the neat line 'Chell built - well built:' The electrical installation and lighting was done by Attenborough & Turpin of Goldsmith Street, while L. V. Pannell of Sherwood Street supplied and erected the neon signs. Heating and ventilation was undertaken by Goodacre, Glover & Butler Ltd. of London Road, who declared that the Dale was the twenty-first cinema in Nottingham that they had worked on. William Bee & Son of Lammas Street likewise described themselves as 'high class decorators and cinema specialists'. To the modern reader, perhaps the most surprising firm associated with the Dale Cinema was Griffin & Spalding Ltd., here announcing themselves as 'theatre and cinema contractors'. Their advertisement went on to say that 'The whole of the chairs, tableaux curtains and curtains for the Dale Cinema were made, fitted and designed by us. We have also supplied, made and fitted the whole of the theatre with hair carpets'. Clearly Griffin & Spalding were proud of their work in the Dale, as a half page advertisement in the Nottingham Journal carried a large, if rather murky illustration of its auditorium. The press referred to Griffin & Spalding's 'manufacturing triumph' in the production of cinema furnishings, remarking that the company turned out 60,000 cinema seats in a year. Apart from Sneinton, places which had received the benefit of their expertise included such improbable centres of entertainment as Swadlincote, Coalville, Walsall and Blaenau Festiniog. The local press stressed that all the seats were made in Griffin & Spalding's Chesterfield Street factory here in Nottingham, and brought in one delightful period touch: 'the fact that they are perfectly silent tipping chairs is an appreciated asset, and one of the novelties introduced is a place for the hat'.

The Nottingham Guardian felt that Sneinton readers would like to know 'to whom they are indebted for the erection of the Dale Cinema', and proceeded to mention the directors of the company. They were the same gentlemen who had opened the Tudor Cinema at West Bridgford and re-opened the Plaza (formerly the Palace) on Trent Bridge. Indeed the application for planning permission for the Dale had been in the name of Tudor Cinemas Ltd. The architect, Mr. Thraves, was one of the directors, as was Mr. W. Chell, the builder.

Other local businessmen on the board included Mr. Sam Graham, formerly Midlands representative of First National and Warner Brothers, the American film syndicates, and Mr. Bertram D. Edwards who, by the time of his death in 1970 was a director of fifteen companies and a hotel owner. The chairman of Dale Cinema Ltd. was Mr. George Herbert Cooper of West Bridgford, who had a closer link with Sneinton as Managing Director of William Lawrence & Co., the Colwick furniture manufacturers. Mr. Cooper had worked for Lawrence's since 1883, when he started as a clerk. On his death in 1937 the Evening Post's obituary of Mr. Cooper revealed an interesting and unexpected side of him. As a young man he had been a fine athlete, enjoying such experiences as swimming in a race against Captain Webb, taking part in a pony race with Fred Archer, the celebrated Victorian jockey, and once bowling out W. G. Grace in a cricket match at Cheltenham College.

In a short speech Mr. Cooper greeted a packed house at the opening performance on Boxing Day afternoon, expressing the hope that local residents would patronise the new venture, and congratulating the builders on their speedy work in erecting the cinema on what had been, only five months before the opening, a piece of waste land. Mr. Cooper told the audience that the directors had received goodwill telegrams from Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, United Artists, Fox Films, and other picture-producing companies. A telegram had also arrived from Johnny Weismuller, of whom more later. Also present for the first performance was Mr. Fred Poulter, the newly-appointed Manager of the Dale Cinema. Mr. Poulter was no stranger to Nottingham, having been for some years assistant manager of the Empire Theatre here. He too addressed the patrons, assuring them of his determination to keep the Dale 'in the forefront of Nottingham's picture houses'.

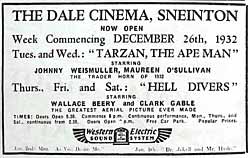

The new cinema opened its doors at 2 p.m. on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays for continuous performances beginning at half-past-two. On the other weekdays the doors opened at 5.30 p.m. for a six o'clock start; there were of course no Sunday performances at this date. Evening patrons paid 7d. or 9d. for a seat in the stalls, and 1/- or l/3d. for the grand stalls; 'the two parts of the house' noted the press 'are entirely distinct'. Cheap matinee prices were available before 4 o'clock on early opening days.

As may have been guessed from the telegram sent in his name, the Dale's inaugural film starred Johnny Weismuller. This was 'Tarzan, the ape man', co-starring Maureen O'Sullivan. (On the day that I write this comes the announcement on BBC news of Johnny Weismuller's death.) For the second half of the opening week the feature film was 'Hell divers', billed as 'the greatest aerial picture ever made', with Wallace Beery and Clark Gable. Other films screened during the Dale cinema's first month included 'As you desire me', starring Greta Garbo, 'Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde', with Fredric March', 'Letty Lynton', with Joan Crawford and Robert Montgomery, and 'Jack's the boy', starring Jack Hulbert and Winifred Shotter.

Thereafter the Dale settled down to the typical routine of the suburban cinema, its history marked only by the programme advertisements in the evening papers. A dip into the files of the Nottingham Evening News revealed that the Dale signalled its tenth anniversary (had it but realised it) with three days of 'Old Mother Riley's circus', supported by '40 minutes of circus variety'. 1943 was brought in by Gene Autry in 'Down Mexico way' and Wendy Barrie in 'Public enemies'. The following Sunday's performance (Sunday cinema had reached Nottingham in 1940) featured 'It's in the air', starring George Formby, and the classic wartime documentary 'Target for tonight'. January 1943 offered such varied fare as 'Woman of the year’, with Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, and Albert Modley and Wally Patch in 'Bob's your uncle'.

Ten years further on, the night of December 27th, 1952 saw the Dale Cinema fighting off the threat of television with Forrest Tucker and Vera Ralston in 'Thunder across the Pacific’. The first Sunday of 1953 had Tyrone Power and Joan Blondell in 'Nightmare Alley', with episode 1 of 'Superman', while the following week saw what was surely an attempt by the Dale's management to offer something new as a counter-attraction to t.v. This was a 'Grand Talent Show: 60 minutes non-stop variety', performed once-nightly. As well as enjoying the cream of the local talent the audience were able to see a feature film. The first half of the week offered John Wayne and Susan Hayward in 'The fighting seabees', changed on Thursday for 'Outcast', with Randolph Scott. Sunday seems to have been old favourites' night, presenting as it did 'Old Mother Riley overseas' and 'Meet Sexton Blake'. On January 16th patrons were regaled with Bob Hope and Jane Russell in the newly-released 'Son of Paleface'. It was, however, all to no avail.

The Dale managed to carry on for a few more years, beset like all cinemas by entertainment tax and the twin enemies bingo and television. On Easter Saturday 1957 though, its doors closed to the public for the last time. So far as one can tell the end of theDale cinema went unremarked by the local press, only its absence from the following week's cinema adverts betraying its passing. At least it ended on a high note with a double bill of 'Doctor in the house', starring Dirk Bogarde, and 'Genevieve', with John Gregson, Kenneth More and Kay Kendall. The reason for the press's indifference to the Dale's closure is not hard to find. It was the eighth local cinema to shut down in a little over two years, following into limbo such varied places of entertainment as the Queen's, Arkwright Street, the Cosy, Netherfield, the Palace, Bulwell (which had all gone in 1955), and the two Hyson Green cinemas, the Boulevard and the Grand, which ended their days in 1956. 1957 had already seen the last of the Imperial, Wilford Road and the Bonington at Arnold, and on April 27th, just a week after the end of the Dale, the Odd Hour Cinema on Parliament Street was to go. In circumstances like these the closure of yet another cinema just was not big news. The Dale was the second of neinton's cinemas to be built and the second to close. The Palace on Sneinton Road had finally shut down in 1945, while the Rio (not opened until November 1939) was to linger on until 1959.

The old Dale Cinema building did not lie disused for very long. In 1961 Wireohms Universal Ltd., makers of electric elements, moved in. Wireohms began in 1932 on Castle Gate, Nottingham, and before moving to Sneinton Dale had also occupied premises at Stoney Street, Peas Hill Road and Bunny. At Sneinton the firm still remains, and the erstwhile cinema survives too. Its sleek lines have suffered from the removal of the tops of the stone decorations at either end and the middle of the facade. Similarly, the insertion of utilitarian windows has played havoc with the striking horizontal impact of the building, and the loss of its canopy has not added to its beauty. Nonetheless the building is still emphatically a former cinema and could not really be mistaken for anything else. Perhaps we should not be too sad about it; the Dale provided employment for Sneinton people during its construction, and in its present guise it no doubt still does so. In between times, for nearly a quarter of a century, it fulfilled the Nottingham Journal's prophecy that it would be 'a very distinct acquisition to the amenities of the Sneinton district of Nottingham'.

THE OLD DALE CINEMA AS IT IS TODAY.

THE OLD DALE CINEMA AS IT IS TODAY.

< Previous