< Previous

Two Sneinton men of verse

By Stephen Best

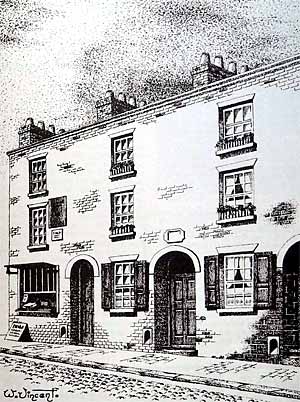

No. 32 WALKER STREET where Millhouse died.

No. 32 WALKER STREET where Millhouse died.Drawing by Bill Vincent based on illustrations kindly provided by Nottingham Local Studies Library

On page 147 of Dearden's Directory of Nottingham for 1834 is a list of 'miscellaneous' residents of Sneinton. These were the people who did not fit into into the usual occupations of bakers, farmers and shopkeepers and comprised largely the gentry, clergy and lawyers of Sneinton. Two names attract attention because of the descriptions appended to them; 'Robert Millhouse, author, West Street' and 'Thomas Ragg, author, Haywood Street'. Largely forgotten today, both men were prolific poets, and Robert Millhouse still has his memorials in Nottingham.

Millhouse was born in St. Mary's Parish, Nottingham, on October 14th, 1788. Research carried out early this century suggested that his birthplace was in Mole Court, off Milton Street, a location blotted out by the building of Victoria Station in the 1890s.

According to his elder brother John, Robert's parents were so poor that they were obliged to put him to work at the age of six and when he was ten to find him employment as a stocking frame knitter. His education was almost non-existent and he learned to read at Sunday School. In 1810, when he was 21, Robert Millhouse enlisted in the Nottinghamshire Militia, and wrote his first poem, 'Stanzas addressed to a swallow', at Plymouth, where he joined his regiment. About this time he asked his brother John to approach the editor of the Nottingham Review to see if he would be willing to publish some of Robert's verses in that paper, and, encouraged by a favourable reception of his work, produced in 1812 the poem 'Nottingham Park'. The Militia was shortly afterwards posted to Dublin, but was disembodied in 1814, when Robert Millhouse returned to his trade at the stocking frame. Three years later he was found a place, as a corporal, on the permanent staff of his old regiment. It is not clear how much security this job represented, since in the years to come he spoke of writing his poetry in the hours when he should have been asleep after sixteen hours at work.

In 1818 Robert Millhouse married Eliza Saxby at St. Mary's Church, and over the next sixteen years he seems to have moved from house to house within the less fashionable parts of Nottingham. Searching in parish registers, the local writer Alfred Stapleton concluded that the Millhouse family lived at various times at Charles Street and Nile Street (near the present-day Huntingdon Street Post Office) and at Mount East Street and St. Ann's Street (at either end of the Victoria Centre). The indefatigable Stapleton traced the baptism of seven Millhouse children between 1820 and 1833, and the burials of three of these same children. By 1833 Robert Millhouse was living on the edge of Sneinton, in Gedling Street, and as we have already seen, he was resident a year later in West Street, at the bottom of Sneinton Road. In 1832 Millhouse had been able, through the kindness of his friends, to give up his framework knitting for a time, but shortly afterwards his wife died, leaving him to look after their surviving children. The writer's friends rallied round once more and Millhouse was found a job at the Savings Bank which kept him in modest comfort. On November 5th, 1835, he married Marian Muir, 22 years his junior, at Sneinton church. Two children were born of this marriage, in 1836 and 1838, by which time the nomadic Millhouse had moved to Walker Street. Early in 1838 the first signs of the poet's last illness (an intestinal complaint), had appeared.

He became very weak and unable to leave his bed for a time, then recovered a little, but catching cold on the day of Queen Victoria's coronation, he never left his home again. The Savings Bank treated him well during his illness, paying his wages, apart from the last three months of his life when he had to subsist on a pension of 4 shillings a week, together with what his ever loyal friends contributed. On April 13th, 1839 he died at 32 Walker Street. To his friend, the writer Spencer T. Hall, he said 'Spencer, my family belong to my country: my fame I leave'.

But what fame did he leave? The fact is that for a time his reputation was very high and his works enjoyed a serious readership. In a way Robert Millhouse was the archetype of the romantic vision of the struggling writer; always on the edge of poverty, if not actually overwhelmed by it, he laboured to produce his verse in the face of weariness, lack of time, and insufficient patronage. Two volumes of poems, 'Vicissitude and other pieces' and 'Blossoms', came out in the early 1820s and for the first of these books Millhouse did manage to gain the support of the Duke of Newcastle. Both books met with a moderate reception and Millhouse can have made hardly anything out of them. In 1826 there appeared 'The song of the patriot; sonnets and songs', which according to one onlooker 'placed him in the first rank of England's 'uneducated poets'', despite the fact that most of the poems had been composed while Millhouse was working at his stocking frame. Some idea of the struggle he was experiencing may be gained from the fact that he was able to find only 77 pre-publication subscribers, and that the majority of these were in London, where Millhouse was comparatively little known. It must have been a great disappointment to him that so few subscribers should have been forthcoming in Nottingham, where Millhouse must have felt he deserved some encouragement. The critical reception which greeted 'The song of the patriot' caused him to believe that he could rely on literature alone for his livelihood, but his health was too poor for him to be able to write for consistent periods of time, and so he was obliged again to take up work at the stocking frame, a course of action which inevitably led to a further deterioration in his health. Of 'The song of the patriot', the Gentleman's Magazine remarked that 'we now behold the fruits of genius', while the Atlas Newspaper considered Millhouse 'a much more genuine poet than many who have made much greater noise in the world'. In 1827 Robert Millhouse published 'Sherwood Forest and other poems'.

The title poem was a theme which had occupied his mind for some time. In it Millhouse expressed his love for the local countryside, his sentiments of patriotism, and his love of God and natural creation. For this volume he was able to attract 91 subscribers, who included some of his staunchest friends in and around Nottingham, such as Colonel John Gilbert-Cooper-Gardiner of Thurgarton Priory, the commanding officer of his old regiment, and Mr. Thomas Wakefield, cotton spinner and sometime Mayor of Nottingham. The affectionate references in the poem to local places caused Millhouse to be tagged 'the Burns of Sherwood Forest', and the fact that he could be mentioned in the same breath as the far greater Scottish poet indicates how highly he was regarded by some.

In 1832 he began to write 'The destinies of man', which was published in 1834. As mentioned earlier, his friends had rallied round in 1832 to make it possible for Millhouse to write without the pressure of having to earn his living at the stocking frame and indeed 'The destinies of man' was regarded as his finest work. Once again, though, the poem did more for his reputation than for his pocket, and literature never remained his sole source of income.

Millhouse's gravestone in the General Cemetery.

Millhouse's gravestone in the General Cemetery.On his death in 1839, Robert Millhouse was buried in the newly-opened General Cemetery, by the Talbot Street boundary wall. For some years the grave remained unmarked but eventually a subscription was opened for the memorial stone which still stands there. It consists of a tablet with an Aeolian harp and laurel wreath above and bears a short verse whose message is that when the Trent stops flowing and the spring fails to bring blossom, then, and only then, will Millhouse's fame die. Some forty years after his death, interest in his work was revived by a reissue of some of his poems, edited by the Borough Librarian, J. Potter Briscoe and it seemed that that was the last that would be heard of Robert Millhouse.

In 1900, however, the contents of the will of Mr. William Stevenson Holbrook, late of Bentinck Road, were put before the City Council. Mr. Holbrook had set aside money for memorials to six Nottinghamshire poets named by him, and for the marking by tablets of places of historical interest in Nottingham. Millhouse was one of the six to be commemorated and some difficulties were encountered as there was no authenticated portrait of the poet in existence. With the help of Millhouse’s youngest son, then living in Philadelphia, a drawing was made, and a bas-relief in bronze made by the sculptor E. G. Gillick. This was placed in 1904 under the colonnade at the entrance to the Castle Museum, and shows Robert Millhouse in profile, with quill pen in hand.

Millhouse's final memorial appeared in 1905 when a plaque recording his residence there was attached to 32 Walker Street. Both plaque and house have long since disappeared, but the poet's other memorials seem safe for posterity.

Perhaps the best picture of the man is in the words of Spencer T. Hall.

'In person of average height, with somewhat grave and striking, but not unpleasant features; a medium complexion, with but little, if any, bloom; somewhat retiring and reflective eyes; an attitude most erect, a stately step, a deliberate utterance and sonorous voice, with now and then a pensive smile'. The Literary Gazette declared that 'From early childhood Millhouse was of an unbending and irritable temper. He considered himself entitled to the sympathy and support of the public, nor would he perform the slightest office that he considered menial or degrading to a man of talent. He was steady and sober, and rigidly honest'. To the Nottingham Review he was 'this ill-fated child of genius'.

Later generations have not judged him so highly. Perhaps the fairest summing up of Robert Millhouse came on the centenary of his death, when a writer in the Nottingham Guardian observed that he could have been a greater poet if he had written in his own vernacular but that he had modelled his style on Shakespeare and Milton, against whom he could only be described as third rate. But, concluded this writer, the acclaim that we have to deny to his poetry can ungrudgingly be given to Millhouse's courage and spirit throughout a life of care and toil.

During Robert Millhouse's last illness, a poetical appeal on his behalf had appeared which ended with the line:

'Nor destitute let Robert Millhouse die'.

The writer of this plea was Thomas Ragg of Haywood Street, the second Sneinton author to be listed in Dearden's Directory for 1834. Born in 1808, he was first employed in a printing office, before being apprenticed to a hosier. He followed this by working at Dearden's bookshop and library on Carlton Street. Dearden's business was taken over by Bell's, the stationers and the building is now the home of the 'Hot Brick' diner. Dearden was of course the publisher of the directory which provides a starting point of this article, and it is a fascinating matter for speculation that Thomas Ragg might have used his post to wangle entries for himself and Robert Millhouse in the Sneinton section of that book.

Ragg began his adult life as an agnostic, or 'infidel', as contemporaries described him, but became fired with the Christian faith. In 1833 he published 'The incarnation and other poems' and a year later produced 'The Deity', a poem in twelve books, considered by The Times 'A very remarkable production, an elaborate philosophical poem by a working mechanic of Nottingham'. The Times went on to say that 'the public should know that the pecuniary means of this gifted individual are so scanty as to make it impossible for him to publish any work at his own expense'.

Spencer T. Hall, a mine of information on both Millhouse and Ragg, tells of an incident at Dearden’s shop, a customer approached the counter and praised Ragg's book in a patronising way to its author. Shortly afterwards, Ragg saw the man in the street and greeted him, only to be snubbed. The pompous customer later told a friend that 'Ragg at Dearden's positively bowed to me in the street, as if we were acquainted'. 'Did he?' replied the other man, 'well, that is very remarkable, considering that when you and I are dead, buried and forgotten, Ragg's name will probably be much more honoured than yours or mine is now'.

If Ragg's name has not come down to posterity, he seems at least to have lived a fulfilled life. After publishing more volumes of verse on a Christian theme, he left Nottingham for Birmingham, where he was involved in the bookselling and newspaper business. In Birmingham, he wrote volumes such as 'Creation's testimony to God', and 'Man's dreams and God's realities'. Thomas Ragg eventually took Holy Orders, being at the time of his death in 1881 Vicar of Lawley in Shropshire, and dubbed 'the adopted poet of the Evangelic muse'.

Spencer T. Hall described him thus: 'Considering that he commenced life so humbly, was self educated and without exception one of the most modest and gentle men I ever met, I have ever regarded his career with wonder, and his character with admiration'. Since Hall himself began work at seven, was labouring at a stocking frame at the age of eleven, and pursued a literary career beset by a frequent lack of money, it is easy to see why he felt such sympathy for Robert Millhouse and Thomas Ragg.

Sneinton can be glad of its association with them both, and they perhaps deserve better than the oblivion into which they and their works have fallen. Though none of their various homes survive, West Street, Haywood Street, and Walker Street all remain to remind one of their literary residents. And one day someone may put a plaque on the 'Hot Brick' in commemoration of Thomas Ragg.

< Previous