< Previous

More or less of a market...

The colourful tale of Nottingham's best-known market

By Stephen Best

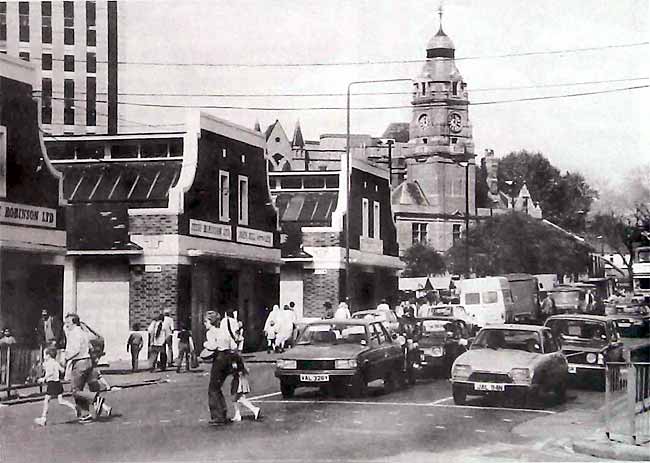

SNEINTON WHOLESALE MARKET with the Saturday market beyond.

SNEINTON WHOLESALE MARKET with the Saturday market beyond.For something that has grown into one of Nottingham's more cherished institutions, the origins of Sneinton Market are surprisingly obscure.

In 1853, the Borough Treasurer's abstract of accounts shows the expenditure of £195 in 'levelling and forming the new markets near Burton Leys and near the Baths and Washhouses', so it is likely that Sneinton Market was first held around this time. In September 1853 the Chamber Committee laid before the Borough Council plans for ranges of shops one storey high, to be erected round a piece of land between the baths and Carlton Road, and proposed that the centre of this area should be left as an open market. Alderman Reckless informed the Council that, as originally put forward, the plan was to enclose the market with a wall and palings, and to provide a house for the market superintendent.

At a further meeting of the Town Council on November 28th, Edwin Patchitt, secretary to the Enclosure Commissioners, indicated that the Commissioners had stipulated that building development in the area must preserve an open space here. He thought, however, that the use of the land for a market would meet this requirement.

By 1858 the market superintendent was reporting to the Council that he had drawn up a scale of charges for market traders, and had arranged for a policeman to collect them. The receipts for the previous eleven months amounted to £9 13s. 4d. A little over a year later it was recorded that cash received for 'market stallages, tolls and standings' at Bath Street market over the last 14 months had totalled £24 4s. 6d., a clear sign that business was on the increase.

Jackson's map of Nottingham, surveyed between 1851 and 1861, and published in the latter year, shows the market established in a triangle of land bounded by Bath Street, Gedling Street, and Wood Street (just about where Freckingham Street now is), and marked as 'New Market Place'. In its early days there was a market every day, and this arrangement was still in force in 1873 when for the first time its existence was noticed by the Nottingham Red Book, a compendium of useful local facts and figures. 'Sneinton Market, so called, is held on an open space of ground on the eastern side of the Borough, near to the Baths and Washhouses, and more or less of a market is held daily, but the principal one is on Saturday'.

The market was a considerable forum for local opinion, and in the Evening Post of October 8th, 1878 there appeared a most aggrieved letter from a writer signing himself 'A lover of the day of rest'. As his nom-de-plume suggests, this gentleman was commenting not on the mercantile aspects of Sneinton Market, but on the Sunday goings-on there. Painting a vivid picture of the breakdown of law and order the writer warmed to his work. 'This place is the resort of some hundreds of men of the lower class, who find pleasure in listening to the 'leaders of the people', whose aim it is to set the dupes that follow them against those in authority, and, in many cases, to defy the law of the land'. The letter went on to allege that 'the language used is most blasphemous and beastly, not only from the mob but the platform of the 'Reformers' or 'teachers''. What had caused the writer to pick up his pen, however, had been a meeting of the Commons Protection League, during which one speaker laid about him freely, abusing 'the Government, employers, landowners, and all classes save sugar boilers'. A young man in the audience queried the epithet 'thief' used by the speaker in connection with a respected Nottingham citizen, whereupon the orator turned on him in such inflammatory terms that 'the mob rushed at him, handling him rather roughly'. Another young man was also set upon, struck in the face, and kicked, and the writer was glad to note that two of the assailants had been arrested. He remarked that such nuisances had been suppressed in Derby and in London, and did not see why he had to put up with rowdy assemblies under his own windows. 'If they must meet', he concluded his letter, 'let them go on the Forest'.

It seems, however, that the crowds continued to gather at Sneinton Market, and if our letter-writer was still alive a dozen or so years later, one piece of Nottingham Street literature would have done nothing to set his fears at rest. This was the manifesto of none other than the Nottingham and District Social Democratic League, a group engaged in 'this great and important struggle for the emancipation of the workers from the vampires of the social anarchy of today'. In a document calculated to make 'A lover of the day of rest' break out in a cold sweat, the league set out its proposals for improving the lot of the worker. Beginning with nationalisation of land, mines and railways, the introduction of equal pay for women, and an eight-hour working day, it continued in a fine crescendo of reform by demanding proportional representation, free school meals, the setting up of a National Bank, abolition of the standing Army, and the disestablishment of the Church. A note at the foot of the manifesto informed interested parties that 'public meetings for propaganda are held in Sneinton Market every Sunday morning at 11 o'clock', so our friend's wish for a peaceful Sabbath must have gone unfulfilled. He would have had one small crumb of comfort in that the Sunday evening meeting was held, not at Sneinton Market, but at 248 Alfred Street Central. According to the Nottingham Street directory, this was Miss Mary Agnes Nunn's Refreshment Rooms, but on the Social Democratic manifesto it was disguised under the ringing title of the Liberty Cafe.

An impression of the character of Sneinton Market at the end of the 19th century may be gained from two articles by William Kiddier, the Nottingham artist, author and businessman. These appeared in a short-lived weekly called 'City Sketches', which came out in 1898 and 1899. Kiddier described some of the more colourful traders, like Michael Angelo Bartelli, an Italian ice-cream vendor, who aspired to making a fortune and returning to Italy to spend it. This gentleman's earrings and red kerchief were evidently a source of wonder to his customers.

Near him stood 'Mr. Brummagem', a jewellery seller resplendent in top hat and starched shirt. He claimed to have been lately in the Klondyke, where gold was so cheap that he had filled not only his bag with it, but also his teeth. His affluent image suffered when he was obliged to ask the stall-rent collector to call again when he had taken in some cash.

William Kiddier also saw a Dutch auction, where the items for disposal included such disparate wares as a pair of skates and a dog muzzle. Kiddier's fine illustrations to his own articles show a rich variety of things on sale; wallpaper, eggs, apples, window-frames, old pots and pans, and second-hand books.

Another character of the Market was Polly Potter, known as 'Watercress Polly', she was a lady of such size that the phrase 'as big as Polly Potter' gained a widespread currency in the area. Tommy Strong, the Sneinton strong man, and others like him, were often to be seen round the Market, which was also a place of entertainment. Down—at—heel circuses and travelling theatres were frequent visitors here. The writer's uncle has told him of his earliest dramatic memory; a man with a ferocious waxed moustache leaping on to a dray, pointing to the Bath Clock, and uttering the compelling words, 'Behold yon lighthouse tower:' Thus began the melodrama of The Lighthouse Keeper's Daughter.

In 1900 the whole aspect of Sneinton Market was changed by the arrival there of the Wholesale Market. This had been held for centuries in the Great Market Place, but when it became necessary to alter the Square to accommodate the new electric trams, it was obvious that another site was needed. To say that the choice of Sneinton Market was unpopular with the wholesale traders would be an understatement. Although the market was only half-a-mile distant from the Great Market Place, it was a good deal less accessible than it is now, and potential customers had to thread their way through an area of slums known as the Bottoms. Economic catastrophe was prophesied, but nonetheless the traders moved; wholesale fruit, flower and vegetable dealers and fish, game and poultry merchants. Along with these came local market gardeners, who sold their produce direct to retailers and large users. They made up the Country Produce section of the Market.

CORNER FEATURE OF FYFFE'S WAREHOUSE.

CORNER FEATURE OF FYFFE'S WAREHOUSE. Sneinton Market still occupied its old site, stretching down Bath Street from Gedling Street to Southwell Road and bounded on the west by Gedling Street and Finch Street (formerly Wood Street), just to the east of the Fox and Grapes pub. Not long after the removal of the Wholesale Market to Sneinton an article appeared in the Nottingham Evening News of 27th August, 1902. This was very critical of the inadequate facilities at the Market, a failing grumbled about by the wholesalers for the next thirty years. In particular the writer stated that the poor conditions at Sneinton would kill the banana market at Nottingham, and that local fruit merchants would have to seek these delicacies at Leicester and Birmingham. The wholesalers' sheds and stalls shot up on the Sneinton Market site, and remained there until the 1930s. Many were rough and ready buildings, and the wholesale market not only made few concessions to advanced ideas of hygiene, but also squeezed the retail market into the adjacent side streets and such corners as the traders could find to set up their stalls.

The Monday and Saturday retail markets continued to attract what the press described as 'trophies from the ragman's trail' and 'mixtures that have defied time and the dustbins of a go-ahead city'. Louis Mellard, writing in the Evening Post in 1925 picks out a few plums; old clothes, soap, boot polish, old washstands, oil paintings, garden seeds, a harmonium, a broken lawnmower, a fireman's helmet, and a first edition of Sir Walter Scott's 'Ivanhoe'. Indeed Sneinton Market became something of a mecca for the book collector. One writer remarked on the poignancy of examining a pile of books, finding in them the signature of a recently-deceased local personage, and reflecting that what had meant a great deal to their late owner meant nothing at all to his relatives. A bookseller especially well remembered was Jimmy Meakin, who habitually wore an old black morning coat, pin-striped trousers, a white shirt with no tie, and a bowler hat. On occasions he completed this resplendent turnout with a pair of white cricket shoes.

In 1934 the City Council at long last got the opportunity it had been seeking to improve the Wholesale Market. A slum clearance scheme provided for the demolition of six streets of back-to-back houses running from Gedling Street to Southwell Road. Accordingly Nelson Street, Pipe Street, Lucknow Street, Brougham Street, Sheridan Street and Finch Street were razed to the ground. On their site was built the new Fruit and Vegetable Market, consisting of four blocks of covered stalls with open avenues. The Fish, Game and Poultry Market, of three blocks, was built at right angles to this on part of the existing Sneinton Market site. Much was made of the modern hygienic features of the new market, such as the roof glass, 'of a kind which reduces the sun's heat and is also a deterrent to flies'. The Fruit and Vegetable section was opened by Alderman Freckingham, Chairman of the Markets and Fairs Committee on June 16th, 1938; the Alderman's part in the planning of the market was recognised by naming one of its avenues Freckingham Street.

During all this time of redevelopment the future of the retail market was under review. It was eventually decided that the Monday and Saturday markets would be accommodated on the Country Produce Market, where they are held to this day. The Fish Market opened in June 1939, followed in the following October by the Country Produce section. After the war the whole of Sneinton Market embarked on a period of expansion, and the committee's annual reports record the milestones. In 1947/48 it was noted that 'consignments of fresh fruit for the Market are flown from the continent to Nottingham Air Port', and three years later it was remarked proudly of the Fish Market that 'many of the tenants have had refrigerators installed in their standings'.

Shortage of space in the Wholesale Market resulted in negotiations with the Post Office for a joint site on Gedling Street, and in 1956/57 the ground floor of the telephone exchange went into market use on a 99 year lease.

It is possible for a disinterested observer to detect a change in official attitudes toward the Retail Market over the post-War years. In the report for 1947/48 the tone is distinctly sniffy; the retail market, we read, 'continues to serve a useful purpose to certain classes of the community in the disposal of both new and secondhand articles'. The following year sees it described as 'in fact, a Petticoat Lane type of market', and by 1951 it is 'recognised as one of the best trading centres of its kind in the country'. The annual report of the Markets and Fairs committee for 1965/66 notes a shift in emphasis from secondhand to new goods. The 1972/73 report logs the increasing popularity of the Retail Market, and expresses regret that room for expansion is not available.

Sneinton Market continues to be an indispensable feature of Nottingham life, and in 1979 achieved the unusual distinction of being the setting of a television play, 'All along the watch-tower' by Stephen Lowe. It is all a far cry from 1873, when 'more or less of a market' was held here. That Sneinton Market is not, and never has been actually in Sneinton, is a trivial detail which bothers nobody.

< Previous