< Previous

The Sneinton Strong Man

By Stephen Best

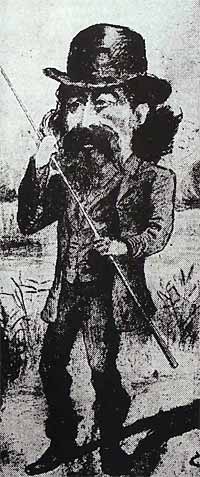

On April 2nd, 1886 a local humorous magazine called 'The Owl' contained a curious cartoon. This showed a man with a luxuriant growth of hair and beard, not unlike the popular pictures of Buffalo Bill or General Custer. He is drawn in the act of catching a sheep with a fishing rod and line in the Grantham canal. This exploit is one of the few contemporary glimpses we get of Tommy Strong, 'the Sneinton Market Samson' Long after his death he was the subject of anecdote and recollection among Nottingham people, and yet hard facts about him are strangely difficult to find. Who was this picturesque citizen, and what exactly did he do that made him such a legendary figure?

Thomas Strong was born in 1847, the son of a Dublin-born coal dealer, after whom he was named, and his Derbyshire- born wife. The 1851 census shows the Strong household at 9 Platoff Street, just about where Pearson's warehouse (the one adorned with the bunch of bananas) now stands adjoining Sneinton Market. Young Tommy was then aged three, and the family consisted at that time of himself, his parents, a younger sister, an older stepbrother and two stepsisters. Later four more brothers and two more sisters were to arrive to fill the little back-to-back house. The family remained here until the 1890s, at either 8, 9 or 10 Platoff Street. Thomas Strong is first listed in a local directory for 1864 as a coal dealer, and by 1883 is described as a coal dealer and goods remover. It seems likely that by this latter date Thomas the younger is referred to, as at the age of 36 he would be far better fitted for such arduous work than his father, who would have been approaching seventy.

Even as a youth Tommy Strong was possessed of remarkable strength and striking physical appearance. The recollections of people who encountered him as a youth suggest that he began his strong man acts by heaving the weights on his father's coal scales. His was a brute strength, without any application of science, and it is possible that he discovered the ability to amuse others simply by larking about in the course of his daily work. It was said that in his early days he was employed in carting away debris and materials from the demolished windmills on the Forest; as the last of these went in 1858 Tommy would have been only 11, a tender age for such muscle building work. In the 1861 census, however, he is described as a 'scholar', so perhaps he merely helped out his father from time to time.

Alternatively, 'scholar' may have been a euphemism for someone who did his learning in the odd moments when he was not required for the family business. The sorting out of fact from folklore is an ever present problem in any attempt to trace Thomas Strong's life, and will be met with again. Quite early in his career he was shrewd enough to recognise the value of a public image, for he boasted that, like Samson, his strength lay in his long hair, and that he would never have it cut short.

In 1928 the Evening Post published the recollections of an 86 year old Sneintonian lady. Her earliest memory of Tommy Strong was of the late 1860s, and suggested a social life more akin to Dodge City than to Sneinton. This was her tale. During Sneinton Wakes, some sort of unofficial fair was in progress on land near one of the pubs on Sneinton Hermitage (probably the White Swan). To this jollification came Tommy, who had only just begun to give public exhibitions, and whose phenomenal strength was not yet common knowledge. Accompanied by a friend, he arrived with his performing mat under his arm. He had no dumb bell weights, and contented himself with lifting anything brought to him, 'such as a donkey, pony, or small cart'. On this occasion he found a visiting heavyweight from Doncaster lifting a 120 lb. bar above his head with one hand, and challenging all comers to emulate him, with a prize of 10/- for a successful attempt. Tommy Strong, without removing his coat, lifted the weight with the Yorkshireman still attached, whereupon that disappointed Hercules declined to pay. up as Tommy had used both hands. Our hero then tossed the bar into the air with one hand, and casually caught it in the other. The onlookers demanded that Tommy Strong be paid, and the pride of Doncaster gloomily turned out his pockets, eventually coming up with 9/4d., which included all the coppers he had taken that day. He attempted to save face by speaking slightingly of the Sneinton strong man's long hair, and suggested a bare knuckle bout to settle the honours of the day. Tommy's friend, a noted performer in the prize ring, proposed that he should fight the Yorkshireman, as Tommy would undoubtedly kill him. The unhappy man did accept this challenge, and for his pains was knocked down by a blow on the jaw which removed a couple of his teeth, striking his head for good measure on one of his own dumb bells. By the time he came to, Thomas Strong and friend had made off with their 9/4d. to the Flaming Sword on Colwick Street (now Brook Street). There the strong man went to earth, surrounded by a crowd of female admirers.

Before long Tommy was to be seen at visiting circuses which performed at Sneinton Market, impressing the crowds by his trick of swinging 56 lb. weights above his head on the little finger of each hand, or by carrying round the arena a heavy iron bar with three 12 stone men hanging from it. Despite his enormous strength and exotic appearance he was of a gentle nature, especially fond of children who, as may well be imagined, pestered him for demonstrations of his physical prowess as he went about Sneinton and the Meadow Platts in the course of his work. Many years later these children were to remember him as looking like a gypsy, a Texas Ranger, or a Mexican bandit. In his early twenties he acted as a model for the life class at Nottingham School of Art, and at about the same time he went away for a while to join a circus, learning to do tricks on the trapeze. It seems to have been a characteristic of his that, whenever trade was slack, he would lay down his mat and perform in the street, or else offer his services to a music hall. A widely told story was attached to one such occasion about 1880 when he was billed to appear at the Royal Alhambra Music Hall. This place of entertainment, formerly the St. Mary's Gate Theatre, was never one of Nottingham's more successful music halls, closing down in 1883, but in its time it attracted such notable artistes as George Leybourne and Sam Torr. Tommy Strong was disguised by the not very subtle pseudonym of 'Thomasio Strongio, the man with the iron jaw', and was practising a new aerial trick, which apparently required him to hang by his teeth from a rope while five 56 lb weights were attached to his body. An assistant was below, watching him with some concern, and called up to ask Tommy if he was all right. Instead of shaking the guide rope in reply, the strong man was incautious enough to open his mouth and answer 'yes'. Down he came, weiqhts and all, without serious injury, but with another legend attached to him. It ought to be added that another source attributes this episode to a public performance at a circus in Sneinton Market: you can never be sure with Thomas Strong. One year he appeared at a circus in the old Cattle Market On Burton Leys, pulling successfully against two cart horses, and ending his part of the proceedings by carrying a donkey out of the ring on his shoulders.

These activities must have kept him in perfect condition for his daily work as a coal dealer and goods remover. He was frequently employed in moving and setting up lace and hosiery machinery, and it was said of him that once he had got his load settled on his back, he would carry five or six hundredweight up or down stairs without assistance. When his day's job was done he would often respond to the requests of watching children by lifting up first the cart and then the horse.

We now come to the incident which gained for Tommy Strong the minor distinction of a cartoon in 'The Owl' in 1886. While fishing in the Grantham Canal he is said to have cast his line too far, and in pulling it back through some reeds to have come into contact with an object which offered great resistance. Whether he thought he had caught a pike, or become entangled with the bed of the canal, will never be known, but what seems to be certain is that a canal official came on the scene just in time to see the Sneinton strong man reel in a sheep, into whose fleece Tommy had cast his hook on the far bank. Pausing only to remark that it was the first time that he had seen anyone fishing for mutton, the canal man made off, doubtless to tell the editor of 'The Owl'. If the cartoon is accurate, by the way, we may take it that Tommy Strong did his fishing dressed in an extremely natty bowler hat.

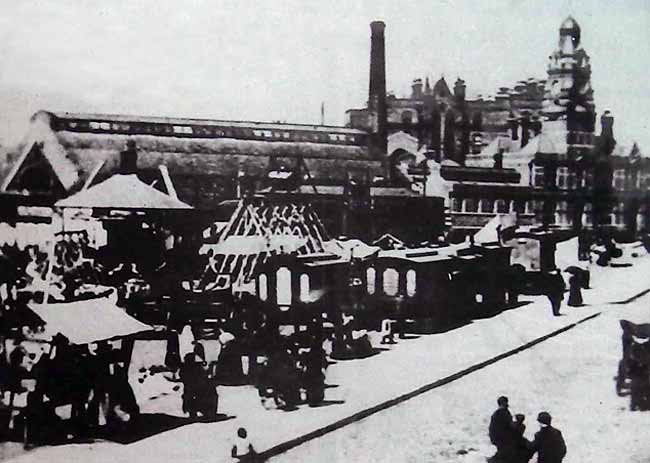

Sneinton Market in the 1890's (photograph by courtesy of the Local Studies library).

This kind of life must have required a man in his physical prime, and it is not long after this that a decline in Tommy's fortunes may be detected. The 1891 directory lists him not as a coal dealer and goods remover, but as a firewood cutter. By 1896 he had moved to 18 Tyler Street, where Sneinton House men's hostel now stands, and after this date he is listed no more. Forty years afterwards an acquaintance recalled the pathetic contrast between the professional strong man in tights and leopard skin, and the hollow cheeked figure with spare frame and grizzled hair chopping sticks in Sneinton Market and pushing them about the neighbouring streets in a handcart.

Tommy Strong's date of death has previously been given as October 4th, 1900, but a search for his death certificate has revealed that he died of heart disease and tuberculosis at Beech Avenue Temporary Workhouse, Sherwood Rise, on October 2nd, 1901.

He was 54 years old, and described as 'formerly a general dealer of Tyler Street'. Tommy's passing was not entirely without notice, since the writer of the 'From Day to Day' column in the Nottingham Daily Express clearly had affectionate memories of him. Referring to him as 'the once picturesque but lately somewhat dishevelled personage known as Tommy Strong', the writer goes on to mention that Tommy’s burial in the General Cemetery was attended by a large number of people, and remembers him as 'Nottingham to the backbone in speech'. The column relates that Tommy had often been seen trudging back home with a hundredweight and a half of apparatus in a sack over his shoulder. 'He pretended that the exercise did him good' concludes the journalist.

The last word must be with the old gentleman who wrote about Tommy Strong in 1932. 'He held an excellent character for honesty, sobriety and industry, and always did his best to oblige those who employed him. Naturally, he was respected for his good character, admired for his strength, and laughed at for his simplicity, which was not devoid of wit'.

Such was Thomas Strong, the Sneinton strong man. He is virtually forgotten today, yet one feels that many a pub has been named after a character less deserving of a place in posterity.

STEPHEN BEST

< Previous