Further Notes on our Topographical Prints

By Alfred Parker

MY article on Topographical Views has brought a request that I should say something more under this heading, particularly as regards the subjects rendered by Thomas Allom.

As stated last month, Allom was trained as an architect, and turned his attention to Topographical work while travelling to enlarge his knowledge in his chosen profession.

We must consider ourselves fortunate that he did so, for he has left records of scenes which are not only valuable historical records but are charming in their pictorial sense.

He toured England extensively, for we find views by him taken in most parts of the country. There are no less than eighteen relating to Nottinghamshire in the volume dealing with the Midland Counties, published in 1836. To these plates descriptive matter was supplied by T. Noble and T. Rose, and the title page gives some idea of the scope of the work in a verse of Charles Hammond's:—

—"Castles 'mid princely parks are there, While hill and valley, rich with flocks and herds, Embank the meadows where the rivers flow, And industry in towns and hamlets shouts; There cities rear their learned halls, and marts With varied fabrics crowd the wealthy ports."

It was at one time a habit of dealers to destroy many of these illustrated volumes in order to get the best price possible for the plates which, distributed, commanded a better price than did the book as a whole. Thus one frequently meets with these engravings divorced from their original binding.

Naturally the great houses of the county figure prominently, thus we have Clumber, with a lively group of figures, a rather intimate touch being given to the scene by the introduction of a chair, upon which a plumed hat has been thrown, standing on the terrace with its array of sculptured urns.

Rufford, seen across the lake, looks a rather severe and uncomfortable building, but is relieved by two fishermen in a punt.

Allom's figures are usually well placed, and frequently are intended to convey some historical allusion, such as in the view of Newstead Abbey from the terrace. Here peacocks strut, while the young Lord Byron and his mother are attended by the poet's faithful dog Boatswain.

Another view of Newstead portrays the lake as a foreground, across which a boat is being rowed by four oarsmen, while the coxswain, in Naval attire, points out the features of interest to the two passengers. It must be admitted that the swans which confront each other in the foreground have a very "Christmas cardy" sort of appearance; birds were evidently not Allom's strong point. In contrast the sportsman who is having a shot at a hare bolting for cover, in the view of Southwell, is full of vigour; sport, too, is suggested in the Worksop Manor which, with its classical facade, lights up the background to an equestrian group, beyond which is seen a pack of hounds crossing the spacious lawn.

Welbeck Abbey is set in its well-timbered park, deer are studded about the open and beneath the trees with their carpet of bracken, but Wollaton Hall, one of its towers shadowed by a passing cloud, is the most pleasing of the "houses."

Market Place, Nottingham, by Thomas Allom.

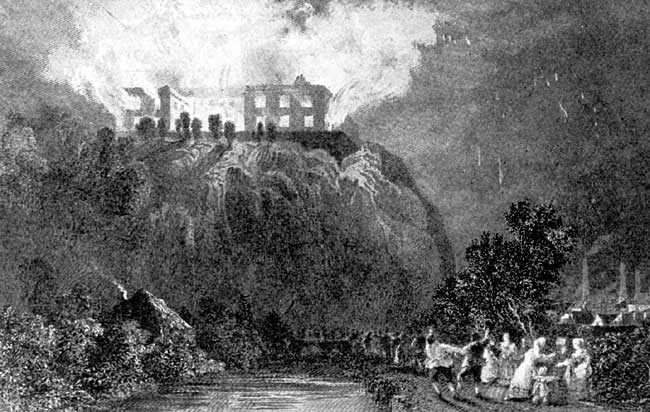

Nottingham Castle, by Thomas Allom.

Nottingham provides four subjects:—

From the summit of Carlton Hill we gaze up the Trent Valley, pass the sails of the Sneinton Mills to the town on the right; in the middle distance the London Road is marked by Trent Bridges and the flood arches, while further still the bluff's of Clifton and Chilwell face each other. In the foreground a ploughman, pausing at the end of his furrow, stands in conversation with a man and woman. The whole scene is flooded by the soft light of a sinking sun. How different the lighting here from that in which we see the Castle blazing as a result of the incendiarism of the Reform Rioters. Sparks fall, boys rejoice to view the lurid flames, and a mother turns protectively to shelter her child, awed by the sight.

The Market Place with its bustle of folk and cattle, its stalls grouped before the old Exchange, preserves for us a picture of the place as it was before the present classical facade and dome dwarfed the open mart.

Radford Folly, the local Vauxhall of those days, now swallowed up in the bricks and mortar of a closely built industrial neighbourhood, speaks of care-free hours spent in open air pursuits or in dalliance with the fair.

There is also an imaginative rendering of the entry of Edward III and his supporters into the Castle by way of the rock passage, which ended in the capture and ultimate death of the Earl of March. The scene depicts the party at a bend in the sloping passage where the wall has fallen away and glimpses of the country beyond are seen through the openings. As this incident supposedly took place at night, and in the fourteenth century the rock sides would have been intact, this venture into the sphere of historical painting is somewhat misleading. How well the artist could appreciate the dramatic possibilities of artificial light may be gathered from the "Monument of Lord Byron, Hucknall Church," where a group of visitors, under the guidance of a verger, stand gazing at the mural tablet, while through the east window the full moon casts a cold light.