County Families and Mansions: STAUNTON HALL

By the Rev. G. W. Staunton

STAUNTON HALL—the South-west Front.

SITUATED sixteen miles from the county town of Nottingham, at the point where the counties of Nottingham, Leicester and Lincoln meet, Staunton is an oasis of quiet beauty and historic interest in a locality which most people regard as neither picturesque nor interesting.

Seven miles to the south-east stands Belvoir Castle on its hill overlooking the vale, which for the most part its lords held in fee, and it is only in the past few years that lands adjoining Staunton ceased to pay rent to the successors of Robert de Todeni, on the breaking up of part of that splendid inheritance as an aftermath of the Great War.

The association of Staunton with Belvoir began at any rate at the Norman Conquest, though in Elizabethan times it was held to have begun before; but contenting ourselves with the Domesday record, we find that in 1086 the central manor of Staunton with its appurtenant land in Alverton, Flawborough and Dallington, was held of Walter de Aincurt by Mauger, the ancestor of the present Stauntons of Staunton.

It would seem as though the Norman Lords of Belvoir granted the Manor of Staunton to Mauger on the feudal tenure of Castleguard, and a certain Robert Cade, who seems to have occupied the comfortable post of family bard at Staunton in Elizabethan times, gives the views of his period on this tenure thus. Speaking of Sir Mauger, he says:—

"In Belveor Castle was his houlde That Stauntones Tour is highte, The strongest forte in all ye fronte And hiest to all mens sighte. Unto which Forte with force and flagge The Stauntons stocke must stick For to defend against the foe, Which at ye same could kicke. His lodging large in yt turritte At all times for his ease, He may command both night and day And noe man to displease. And therefore Stauntons maner now Which in Staunton doth stand, Of Belveor Castle is now helde By tenure of the lands."

As verse Cade's efforts are deplorable enough, but he, we know, had access to documents since lost, and we may be grateful to him for recording the inscriptions on all the Staunton tombs then existing, many of which, in the troublous times of the Civil War, and the later but no less destructive restoration of Staunton Church in 1852, were removed or otherwise disappeared.

This association with Belvoir was not always to the advantage of Staunton. Thrice, between 1582 and 1612, the owners of Staunton, being minors, became wards to the Earls of Rutland, by tenure of their land.

The marriage of Anthony Staunton to Frances Palmer arose from a game of bowls at Belvoir, when one Dallington, to whom Roger, then Earl of Rutland had assigned the wardship, wagered it, and lost it to Matthew Palmer of Southwell. As a consequence Anthony Staunton was married to Palmer's sister and during the minority of the young heir, and also that of his son, Matthew Palmer administered the revenues of Staunton, with results, satisfactory possibly to himself, but decidedly not advantageous to the estate.

These wardships came to an end with the Restoration of Charles II, but the ancient tenure of Castleguard is still commemorated in the Staunton Tower at Belvoir Castle, the golden key of which is presented by the head of the Staunton family on the occasion of the Sovereign paying a state visit to Belvoir Castle; and in the provision of a bell rope to Bottesford Church in order that, when Belvoir was threatened, aid might be summoned from the inhabitants of the Vale.

From the Conquest downwards the descendants of Mauger have continued to hold the Manor of Staunton, their possessions in other manors waxing and waning in accordance with the thrift or extravagance of the owner, or the vicissitudes of the times.

After the Civil War they lost all except a few acres, but the manorial rights were preserved, and after years of careful living and saving every acre in the parish was regained in 1830 with the exception, of course, of Church lands.

There were two manors in Staunton, the second one being Staunton Haverholme, an appurtenance of the Priory of Haverholme in Lincolnshire. On the Dissolution of Monasteries this manor—now known as Staunton Grange—was granted to Sir Thomas Tresham and George Tresham, and shortly after came into the possession of Jerome Brand who married the daughter of Anthony Staunton. Their son, Robert, sold the manor to William Staunton, in whose family it continued until the troubles of the Civil War caused Col. William Staunton to sell the land in order to pay the fines and levies made upon him by the Parliament; but the manorial rights were retained by the Stauntons.

Until these two manors were united under one lord there were continual disputes between the several tenants. While the Priors of Haverholme were in possession they seemed in general to come off best, but after the dissolution things changed and Robert Brand, the new owner of Staunton Haverholme, had to take the second place though most unwillingly he did it. The Court Rolls bear witness to the heat developed on both sides at the Manor Courts and the Staunton papers reveal frequent but unavailing attempts by Robert Staunton (d. 1682) to come to terms with his brother-in-law.

Mention has been made of the Staunton documents, and it may here be stated that probably no family in this country possess a more complete set of documents relating to a property possessed by them from Norman times. Preserved from 1190 downwards we find charters running well into thousands relating to properties in Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire and as far afield as Suffolk. Saved, somehow, when Staunton Hall was occupied by the soldiers of the Parliament, when all the furniture was looted and sold; saved again time after time when individual possessors regarded them as useless lumber, they were used by Dr. Thoroton in his history of Nottinghamshire, and were laboriously transcribed by Charles Mellish of the Hodsock family, 1775 to 1796, in some fifteen volumes of manuscript, while since then, from lawyer's offices and lumber rooms, at least as many again have been gathered, though these later discoveries are of less interest than the original collection.

Nevertheless among them is included the long lost note book of Robert Staunton containing 130 pages of manuscript, begun in 1561 and ending in 1580, which gives details of his family, his rentals, of his seventy-three god-children with the christening gifts he presented to each, and much more of interest.

This book is frequently alluded to in the marginal notes of Dr. Thoroton's history of Nottinghamshire, and provided him with much of the material used in his records of Staunton, Alverton, Kilvington and Flawborough, all of which places were in Robert Staunton's possession when he died.

Anything that Robert Staunton considered of importance he noted in his book, for instance, when he built the Porch at Staunton Hall he records the amount paid to each tradesman, while in 1568, after detailing some additions he had made to the house, he finishes the entry thus: "Bought a bed-sted for myself which was XIIIs IIIId. I thank God."

In 1567 he records that while he and others were ringing the Church bells for Evensong, the great bell fell and passing between the ringers fell to the bottom of the Church tower without injury to anyone. He describes the repairs he had made to the tower, and the inscription he caused to be placed on the new work.

Perhaps the least satisfactory of his notes is the one where he tells how he sold the chalice and patten from the Church, and invested part of the money in a book of Homilies which is still in the Church chest.

Nevertheless, Robert Staunton was a man typical of the spacious days of Good Queen Bess, and the number of his god-children alone would serve to show the esteem in which he was held by all his neighbours, rich and poor.

He consolidated his estate by a threefold exchange negotiated between him, Robert Markham of Cotham, and Anthony Thorold of Marston, by which the Markham property in Kilvington, Alverton, Flawborough, and Staunton, passed to Robert Staunton, who in his turn made over his lands in Bassingham, Quarrington, and Sleaford to Anthony Thorold, who passed his lands in Claypole to Robert Markham.

While this exchange was most expensive to Robert Staunton, who paid more than the others, it suited his purpose well, leaving him, as it did, the sole owner of Staunton and its neighbouring villages, with the exception of Church lands and a small property in Kilvington belonging to his relations, the Brooksbys. But he parted with the Lincolnshire lands in Bassingham, Quarrington and Sleaford which had come to his family by the marriage of Sir William de Staunton to Athelin, daughter and heiress to Sir John de Musters, Lord of Bassingham, three hundred years before.

But while recording the happy rediscovery of Robert Staunton's note book we have come too far down the centuries and must retrace our steps to the time of the Crusades.

In one of Mark Twain's books we read that he travelled through Spain and Portugal by deputy, but this easy method of seeing the world appears to have been discovered by Sir William de Staunton in 1189.

This was the time when all England was in a fever of preparation for the Third Crusade, in which Richard Coeur de Lion took the most prominent part. Sir William de Staunton desired to proceed to the Holy Land with his King and took the Cross in his own person. For some reason, however, which is not recorded, he remained at home and sent in his stead Hugh Travers, a villein dwelling on the Alverton portion of the Staunton estate, first emancipating him and his brother John. The original charters—four in number—relating to this transaction are preserved among the Staunton documents and are probably the earliest records of the kind subsequent to the Norman Conquest.

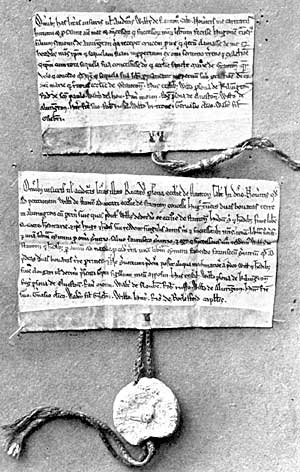

Manumission of Hugh Travers, 1190.

TRANSLATION.

Manumission of Hugh Travers, 1190.

To all men who shall see or hear this writing William de Staunton sends greeting. Know ye that I, for the sake of charity, and for the safety of my soul and of the souls of my predecessors and successors, have made free Hugh Travers, son of Simon of Alverton, because he took the cross in my place, and that I, as regards myself and my heirs, have quit claimed him and his family for ever from every earthly service and exaction, and that I have granted him with all his family to God and the church of St. Mary of Staunton. Wherefore I will and grant that he and his family remain free for ever under the protection of God and St. Mary and the rector of the church of Staunton. Witnesses, William parson of Kilverton, Ralf de St. Paul, Walter del Hou, Ranulf Morin, Roger parson of Elston, William of Alverton, Henry his brother, Robert Russel, William the Breton, Gervase the clerk, Walter son of Gilbert.

To all men who shall see or hear this writing, Richard parson of the church of Staunton sends greeting in the Lord. Know ye that at the request of William de Staunton, patron of the church of Staunton, I have granted to Hugh Travers two bovates of land in Alverton with their appurtenances which the said William has given to God and the church of Staunton, to be holden by him and his heirs freely, quit, and hereditarily. Also the same Hugh and his heirs shall render each year to me and my successors one pound of incense and one pound of cummin, in lieu of all service except service to the King (forinsecum servitium), and I and my successors will render for the same land to William de Staunton and his heirs, each year at Christmas, one pound of cummin, doing (also) the service to the King which belongs to the said two bovates of land. Moreover, lest by any craft the said service may be extorted or withheld from the said William and his heirs, I have set my seal to the present writing. Witnesses, William parson of Kilvington, Roger parson of Elston, Ranulf Morin, Walter of Flawborough, Robert Ruffus, William of Alverton, Henry his brother, Gervase the clerk, Walter son of Gilbert, William, Henry, Richard of Bottesford, chaplains.

It is interesting to note that from the Staunton collection the history of the Travers' family can be traced for about 260 years subsequent to 1190.

This same William de Staunton confirmed to William the Fowler one bovate of land in the territory of Staunton to hold for him and his heirs for ever by the office of Hawking, and the said William the Fowler to be at the table of William de Staunton between the Feast of St. Michael and the Feast of Easter. And of his own property he should make and repair all Nets of Hawking, and everything which belongs to the office of Hawking except a Horse, a Boy, and Mews for the Crane Hawks.

Charles Mellish remarks that William de Staunton must have been very fond of the diversion of Hawking, and that his establishment for his Falconer was very magnificent for a private gentleman in the time of Richard I, the expense of keeping Hawks, even in the reign of Edward I being enormous. The maintenance of one Hawk per day was, if at Court 1½d., if Hawking 1s. This last is worth probably in these post-war days £1 per day. If then William de Staunton kept several Hawks the expense was probably equal to the present cost of keeping racehorses.

The Rent Roll of Thomas Staunton, dated 1440, shows that the Fowler family had died out and their bovate was then held by one Roger Sutton who paid 6s. annual rent for it.

And the same document shows that the two bovates in Alverton, granted by William de Staunton to Hugh Travers at a rental of a pound of frankincense and a pound of cummin, were, in 1440, held by Robert Brydgford and his wife at a similar rent.

John Hopkynson, also an Alverton tenant, paid one pair of shoes at Christmas, while William Aschewell of Flawborough holding a messuage and a bovate and five acres of the Demesne paid yearly 7s. rent, and a goose at Michaelmas, and a shoulder of mutton at the second court after the Feast of the Passion.

Several of the tenants were bound to ride into Scotland in the autumn whenever the Lord of the Manor should ride there himself.

One would like to linger on these ancient tenures but space forbids and we can only refer to the Court Rolls as late as 1807 to show that at each Court the Travers' rent of frankincense and cummin was demanded though never apparently paid; while the Countess of Oxford was shown as a defaulter for £313s. or 220 pairs of gilt spurs, which she and her predecessors should have rendered at the rate of a pair of spurs or 8d. each half-year for land in Alverton known as the "Golden Spur Land."