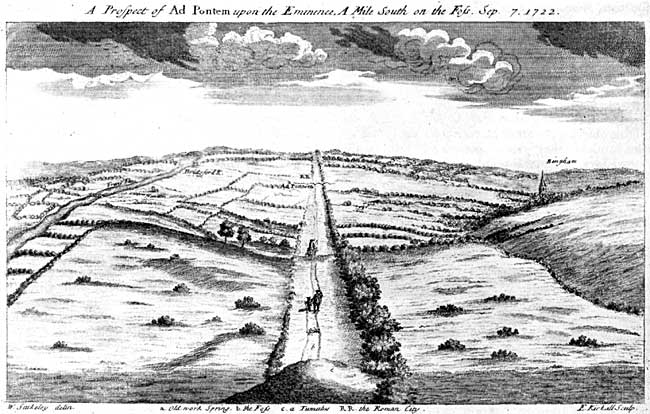

AD PONTEM, from the drawing by Dr. Wm. Stukeley, 1722.

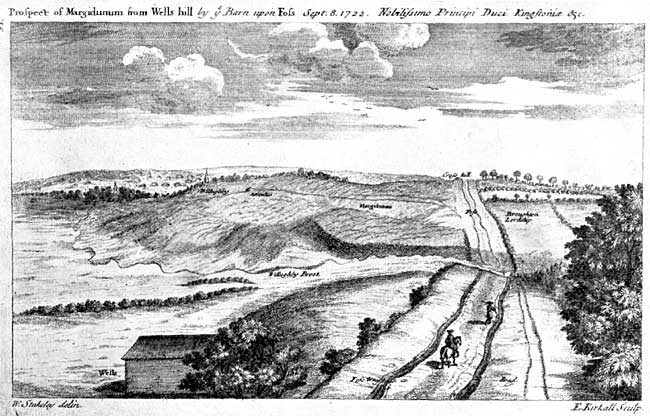

MARGIDUNUM, from the drawing by Dr. Wm. Stukeley, 1722.

With regard to other roads of Nottinghamshire which may be Roman, we enter upon a field of extreme doubt and uncertainty; for it is easy to pick out a straight line on an Ordnance map and to rush to a hasty conclusion that it indicates a Roman road for which, in point of fact, there is no justification. It must be remembered that about two thousand years ago a large part of Nottinghamshire was covered by dense forest, harbouring red deer and wild boar and, no doubt, infested with wolves, whilst the north-east corner consisted of swamp and marsh. The Trent Valley and the Vale of Belvoir would be almost the only inhabitable and cultivated areas, although on the western borders of the forest (of which Sherwood Forest is the remnant) there were Roman villas at Mansfield Woodhouse and Styrrup. These villas must have been situated on roads having communication with the main Roman roads, but clear traces of Roman roads in this area are very problematical and depend for the most part on the dubious authority of eighteenth century authorities. Any attempt to trace out roads in this area is very uncertain work and very little evidence is as yet available. Efforts have been made to establish two Roman roads traversing this part of the county; the first is supposed to run from Bawtry through Blyth and Worksop and along Leeming Lane to Mansfield, proceeding thence perhaps to join the Rycknield Street near Littlechester at Derby. This is pure theory, and is based on finds of Roman coins at Blyth, Worksop and Mansfield, the presence of a Roman villa at Mansfield Woodhouse, and the name Leeming Lane on the Ordnance map. All this is unsatisfactory evidence, since coins in any case are not presumptive of more than a mere pathway. The only proof of a road is visual evidence of a raised and continuous embankment coupled with actual excavation. Packhorse trackways are very different from the carefully constructed Roman highways under consideration.

The other track that is presumed to be Roman is supposed to run from Blyth and perhaps Bawtry through Ollerton in the direction of Nottingham. This is certainly a very old track and in places is still known as the "great way" or the "great street"; where it passes near Rufford Abbey is bordered by a very wide and deep ditch of considerable age. This is mentioned in early records as "the ould dyke." Numerous hill forts of British origin lie on or near this track. It is very straight from Bilby Gate to Ollerton and thence not quite so direct as far as the fork to Oxton. Near this Oxton fork a raised embankment can be traced, running parallel with the present road, and may possibly be Roman, but it needs to be excavated. With a little imagination the line can be carried on to the presumed Roman camp on Cockpit Hill. Mr. Herbert Leman has drawn my attention to the fact that an old thirteenth century map of Bestwood Manor, preserved at Belvoir Castle, refers to this road as the "street in Rumwood " and also marks "the streets in Lambley Wood " (the word Street usually signifies a Roman road). This may be taken to indicate the straight road on the high ground of Mapperley Plains leading to Nottingham and the Trent at Wilford. Here Roman pottery has been found in association with stone slabs in the bed of the river, probably indicating that there was a stone-paved ford across the Trent in Roman times, and thence a road probably led to the Roman villa at Barton-in-Fabis ("Barton among the Beans"). If this trackway through Sherwood Forest is of Roman origin it probably belongs to the later period, e.g., the late second century or the third century, when the majority of Roman villas were constructed. During nearly 400 years of occupation there must have been many trackways and minor roads in the country, but until definitely proved by excavation they are largely the product of guesswork. There have been finds of mosaic pavements at Southwell, indicating a civil settlement, hoards of coins at Epperstone and Calverton, an inscribed ingot of lead from the Lutudarum mines in Derbyshire ploughed up in Hexgrave Park, etc., indicating perhaps a transverse road through the Forest from the Fosse Way to the villa at Mansfield Woodhouse and thence into Derbyshire.

Unless there was impenetrable forest in this district at the commencement of the Roman occupation, it is difficult to conceive why a detour should have been made from Leicester to Doncaster via Lincoln instead of a direct south to north route through the forest. If such a direct route had been possible, it would have been of such importance to trade as to render the existence of the Fosse Way unnecessary at the time when the "Antonine Itinerary" was compiled, viz., at the end of the second century.

With regard to possible Roman roads in other areas there is only one which seems fairly certain, namely, the road which runs from Margidunum through Granby and Plungar to join near Branstone the highway running from Saltersford (near Grantham) to Six Hills. This latter road is admittedly known to be Roman and it is probable that the road to Margidunum would be used for the important purpose of bringing iron ore from the Belvoir Ridge to be smelted in the camp itself, as my excavations have shown. This road has been definitely traced on the east side of Margidunum, whilst a Roman altar has been found at Granby as well as some coins.

On the west side of Margidunum a road, still called Bridgford Street, issued from the western gate of the camp and ran in a straight line down to the Trent at Gunthorpe Bridge, where there was a ford. There is, however, no definite evidence for its continuation on the west side of the Trent, either as a causeway across land liable to flood, or otherwise, but river-gravel was certainly brought up to the camp and the Fosse Way by means of this road.

Much less is known with regard to other roads branching from the Fosse Way. The remains of a bridge supposed to be Roman have been found near Cromwell, and this discovery would naturally lend itself to a road running from Crocolana in a westerly direction across the Trent. It has been taken for granted that this bridge is Roman on the score of its construction, but there is no evidence in the shape of pottery or coins in favour of a Roman date. Moreover the very slight construction is in itself an argument against a Roman date, since the Romans, when they built a bridge, favoured solidity and permanence. There is no trace of any road of Roman character leading to the bridge, and the very fact that on an important and main artery such as that from Lincoln through Littleborough to Doncaster it was considered sufficient to cross the river by a causeway or paved ford instead of by a bridge, seems to militate against the possibility of Cromwell Bridge being Roman. Until more definite evidence is forthcoming, judgment must be reserved. It may indeed have been constructed at the time of the Civil War, in the course of the military operations around Newark; and an old copy of a plan made at that date shows a bridge with stone piers across the Trent, to the north of Winthorpe.

Another road, which may be Roman, can be traced as a ridge through the fields to the north of the railway between Bingham and Radcliffe. It runs from the Fosse Way as far as Radcliffe towards the ferry, but it would seem to alter its direction so as to proceed to the south of the village in a south-west direction towards Barton. Examination of a section of this definite embankment failed to show any indication of a gravel basis, although it was definitely composed of made soil. Either the paving or gravel had been removed or else it was a trackway made from merely the upcast from drainage ditches on either side.

There is a definite Roman road running from Littlechester, near Derby, to Sawley, where it seems to vanish. It is a matter of doubt whether it crosses the river and continues in its line of direction to Vernemetum, but investigation has up to the present failed to show any such continuation.

It may be said in conclusion that in the study of Roman roads in Nottinghamshire there is much yet to be done, but it must be done with the spade and in the field and not with the imaginative methods of eighteenth century antiquarians, an Ordnance map and a ruler. Any trouble taken in this direction, besides providing healthy exercise, is a very real and valuable addition to the construction of the picture of life in Roman Britain.