It was not destined, however, to bear witness to his greatness for long. With the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the hatred of the Royalists for the Commonwealth party was vented both upon the living and the dead. Ireton's tomb was destroyed, his corpse dragged from the grave and hanged at Tyburn, where his head was afterwards displayed upon a pole.

So ignominiously passed the remains of a great man, one who steadfastly adhered to the principles which he considered right, "stiff in his ways," scorning personal profit, but pursuing the ends of the State ruthlessly, and in that pursuit destroying all who stood in the way of what he conscientiously believed to be the common weal, even unto the Monarch himself.

There is trace of a doorway which in the time of the Iretons gave access from the house to the churchyard, by the west-end Tower door. We will, however, use the South Porch and shall not fail to notice the fine door with its wrought-iron-work or the incised stone grave covers with their ornamental crosses.

But it is for the late Norman capitals of the aisle pillars that Attenborough Church is noted. Those on the north side are the earlier, not so deep, more restrained in character. Their opposites display some extraordinary conceits. A mitred Bishop shares stations with a rogue with teeth exposed in a ferocious grin; a pig-faced grotesque neighbours a "pin-head" with clawed fingers.

A good deal of time can be spent upon these very varied types and on seeing them one cannot fail to ask the old question: "Why did the masons carve these weird creatures; what lesson were they intended to convey?"

The aisle windows are of the square-headed form, typical of much Nottinghamshire work at the end of the fourteenth century. The piscina (or bowl for the washing of the sacred vessels) let into the south wall tells us that this aisle was once used as a chapel, while on the opposite side the steps which originally led to the rood loft bear evidence of the screen which once divided chancel and nave. Though this has long disappeared, there still remain in the choir two of the fifteenth century stall ends, with their carved "poppy-heads," placed one on either side of the priest's doorway.

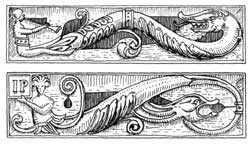

Other interesting pieces of early wood-carving are incorporated in the excellent modern stalls—they are panels of Jacobean time, one depicting a belted horn-player (he is otherwise as void of clothing as the most ardent nudist might desire) charming a great dragon; another portraying a merman with scrolling tail, holding a tablet on which are the initials I P—they are those of John Powtrell, whose arms also occur on a carved wooden shield nearby, dated 1623.

If we peep under the altar cloth there is to be seen a fine, massive table of Elizabethan date; the ringing of the bulbous centre legs has been much chipped, but there are nicely carved lion-head masks on the broad feet.

Much might be said of the various memorial tablets, windows and hatchments, but one simple marble slab on the north wall is of special interest to Freemasons, for it records the interment at Stretton Audley, Oxfordshire, of Admiral Sir John Borlace Warren, Bart., G.C.B. and Guelph, who died on the 22nd of February, 1822. This gallant sailor was Provincial Grand Master of Nottinghamshire from 1802 to the time of his death.

Let us step outside. Here, about the church stand headstones of many fashions; among them the clean-cut long enduring slates, popular a century or more ago, on which are depicted the emblems of mortality and resurrections having something of the flavour of certain "modernistic" art.

Simple and dignified amidst the yews we see a plain square cross, faced with a bronze sword, and beneath the inscription:—

"To the glory of God, and in memory of the men and women who lost their lives in the service of their country in the Chilwell Explosion, July 1st, 1918."

As the memorial window in the north aisle tells the story of those who gave their all overseas, so does this remind us that others were called upon to make the supreme sacrifice in the "home line," and many pages would be required to retail the story of acts of heroism and cool daring which have for their background the terrible catastrophe here recorded.

A more pleasant thought is to dwell on the picture of the Monks of Lenton, who long years ago enjoyed the fishing hereabouts, when the Brook was a more limpid stream. Maybe they loved to tell the same sort of yarns which are still swapped in the snug of "The Bell," tucked away behind the cottages near the end of the path to the river.

The fine specimen of a carp which hangs here was not the trophy of rod and line, however, but was caught by one of the station-masters between the metals of the railway during the floods of 1910.

Attenborough Station Waiting for the 5.8 train. A scene enacted many times each day when the Munition Works at Chilwell were in operation during the War.

Industry has encroached upon Attenborough. As we gain the long platform—extended to unusual proportions to cope with the workpeople who came to the munition works at Chilwell—the incessant seething of the gravel suction plant fills the air. In the great lake now gradually coming into being, the tusk and bones of mammoth have been found. What changes have taken place since these great beasts roamed the Trent Valley. Not many hundreds of yards away lies one of those acres of concrete—a modern by-pass. Yet another has eaten up the pastures.

Let us hope that whatever the fates may yet hold in store for us, the powers-that-be will bear in mind that rural beauty is also reckoned an amenity by those who love the countryside.