West Bridgford: then and now

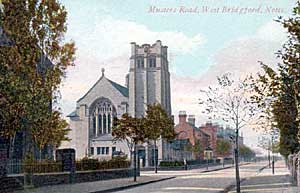

Musters Road, West Bridgford c. 1910.

Musters Road, West Bridgford c. 1910.THE name may be said to contain within itself three allusions to the river Trent. The word "ford" refers to a passage through the river which had from time immemorial served its purpose; the word " bridge " may refer to an improved method of transit over the river adopted a thousand years ago; and the word "West" distinguishes the passage from that at East Bridgford, nine miles eastwardly, where the Romans passed over the Trent on their way from Margidunum to the north of the County.

The Trent was the great highway upon which the Anglo-Saxons came to settle the district, and was at one period the dividing line between the kingdoms of Mercia and Northumberland. When our county was divided for local government purposes into Wapentakes, each of them was framed so as to have direct access to the great water highway. Rushcliffe, Bingham, and Newark hundreds being on the right bank, and Broxtowe, Thurgarton, and Bassetlaw on the left, West Bridgford being the boundary parish of Rushcliffe. The Norsemen ascending the Trent saw the water at spring tides rushing up hill, and attributed its action to their god, AEgir, and to this day the cry of all boatmen in sight is "'Ware AEgir!"—"Beware of the AEgir." At the time of the Domesday book (1086) the Water of Trent was so guarded that "if any one impedes the passage of boats he has to pay a fine of 8 pounds," equal to £240 now; and eight hundred years ago Henry I. committed the care and tolls of the Trent to the Burgesses of Nottingham. "And the passage of the Trent," said Henry II., "ought to be free to navigators, as far as one perch extends on either side of the mid-stream." For many centuries the Trent was the only practicable way of goods being transmitted to or from London. There was a considerable trade done three hundred years ago by coals being sent from Wollaton pits on pack horses (query by Coalpit Lane) to Trent Bridge, to be thence sent to London by boat, the price per ton at the bridge being 6/4, carriage to Gainsborough 3/-, charges there 6d., to Hull 2/-, waste 4d., to London 8/-. "Some all, 20/2." (p. 172 Wol. MS.) The use of the river has long been neglected, but the day may come when that use will be largely extended, for with an improved navigation the trade of the district would be benefited, manufactories established, and the evils of floods lessened. Bridgford and the Trent are inseparable, for at two points the boundary, until recently, entended to the mid-stream, and now to its bank, and the old Trent ran through the parish, as may be seen at the north end of Lady Bay Eoad, where the old course is thirty feet, or so, below the level of Holme Road.

Boundary. A boundary line of the parish may be roughly drawn as follows:—On the eastern side, starting from a point in the old Trent bed, opposite to the western extent of trees in Colwick Park, proceeding southerly by Adbolton Grove to Radcliffe Road, where is a little water course, a little west of Gamston Canal Bridge, and still southerly to the east of Bridgford Covert. There are four fields between that Covert and Meadow Covert, that appear to have been taken out of Edwalton parish. From Bridgford Covert going westwardly by Valley Road, and on until the bend of Wilford Hill is nearly reached; then turning northwardly through the buildings of Willow Farm, and lower down crossing Loughborough Road, going to the west of the houses on that road to the Trent. The line leaves the Lovers Walk, and crossing the adjoining cricket field, it proceeds in front of Trent Bridge Inn, to the north of the houses on Radcliffe Road, but south of the Forest Football ground, by the course of the old Trent, through the railway arch and Trent pools, crossing which, it goes to the river, and returning it follows the course of the old Trent, which may be traced by the willows and the depression, and leaving a big field in Sneinton parish, called The Hook, on the wrong side of the river.

Geology. The principal part of the parish rests upon a terrace of ancient gravel, and river drift, which in some places is twenty feet in depth. What are called Older Gravels extend for three-and-a-half miles to Radcliffe, and "probably belong to the closing stages of the Glacial period, when the rivers were subject to seasonal floods of powerful volume." (Geological Memoirs, p. 8.) The terrace forming Holme Road may be noted. "The thickness of the river deposit on the valley floor has been proved by a well boring near the canal at West Bridgford to be eighteen feet." (Geological Memoirs, p. 60.) The depth of the Old Trent Pool in Boots' Recreation ground is said to be eighteen feet. On the Ladybay estate the old maps showed "Barrow" or "Burrow Hill"; (Query—Had there been a sepulchral ground there?) and the upper strata varied greatly, on Pierrepont Road there being found layers of loam, sand, clay, silver sand, etc., but south-eastwardly there were only a few inches of soil over the clay. The Keuper Marls are below the river deposit, and on the southern side of the parish they form an embankment, best shewn in Mr. Smart's brickyard. In the valley towards Edwalton there is a black soil, peat and alluvial loam, indicating that there must have been, in the days of old, a lake or bog.

Anglo-Saxons. The Anglo-Saxon settlement in the villages on the banks of the Trent is usually assumed to have been about, or before, a.d. 600, and it appears probable that the place now called Bridgford, being so convenient to the Trent, so near to the chief town of the district, with good land, having a fine brook running from a spring on Edwalton hill, and with varied soils, would be among the earliest settled, but we get no reliable information until the time of Alfred the Great, nearly 300 years afterwards. In 868 the Danes occupied Nottingham, and were besieged by Burrhed, King of Mercia, AEthelred, King of the West Saxons, and his brother Alfred, and a treaty of peace followed. In 874 the Danes returned, and conquered Mercia, and governed, by a small exclusive class of military heathen men, from the five boroughs of Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln and Stamford, held down in serfdom the old English and Christian people, and they continued until Edward the Elder, and his sister AEthelflaed, subdued them. In 924 Edward with an army went before Midsummer to Snotinagham, and ordered the construction of a burh, or fortress of earthworks, on the south side of the water, opposite to the other, and a bridge over the Trent between the two fortresses. This provision, with the re-building of the Town Wall, not of stone, but earthworks, and dry ditch to protect St. Mary's hill, would greatly tend to increased security and prosperity. Whether King Edward lived to see the order he gave completed is doubtful, for he died within a year at Farndon, in Mercia, which Professor Oman, in his "England before the Norman Conquest," says was "probably Farndon on the Trent [near Newark] and not the more southerly village of the same name in Northamptonshire." Professor Oman further suggests that "there is some reason to believe that we may ascribe to Edward's last four years of peace the re-arrangement of the territorial division of the Midlands, or at least its commencement. To the towns of Bedford, Northampton, Cambridge, Huntingdon, Derby, Nottingham and Leicester we find appended an "army," and people owning obedience to the town, in most of them a "jarl" is also mentioned. It is hardly possible to doubt that the modern shire simply corresponds to the holding of the Danish "army" which Edward subdued. The casual mention of the chronicle that the lands owning obedience to Northampton reached as far as the Welland exactly describes the modern frontier of its shire. As to the remaining lands of East Mercia, Nottingham undoubtedly bore the same relation to the district around it which now became, as did Bedford, or Derby, to their regions." (p. 511.) We thus see that Edward's work at Bridgford was a part of a general local scheme.

Where and what was Edward's fort ? We must assume it to have been only a stockaded fort consisting of earthworks, timber, etc. The Normans afterwards introduced stone fortifications in castles, and towers, but the Saxons lived more simply, and their defences were more cheaply constructed. Assuming the fortress to consist chiefly of earthworks, supported by timber, it is reasonable to suppose that when the works were discarded as out of date, the soil round about where the fort stood would be left a little higher than the surrounding land. If we thus look out we shall find on the north side high ground, and on the south side the Trent Bridge Cricket Ground was said to be higher than the surrounding land, and seldom or never flooded, and between that ground and the bridge there was sufficient space for the fort, and this may have determined the boundary of the two parishes which here meet.

We are further told that according to Marianus Scotus "Edward did build a Bridge over the Trent and on the other side a little Town over against the old Town of Nottingham now called Bridgeford." This statement occasions a difficulty, because it appears to be probable that a village had long stood where what we call Bridgford now stands, and as suggested by Thoroton, a few buildings at the end of the bridge does not justify the term "a little Town." There is another ancient quotation, "The Trent goes from Clifton to the bridge of Nottingham, called the Trent bridge, and anciently Hethe bothe bridges: at the south end whereof is the town of Bridgeford built by the famous Lady of Mercia, to repress the violence of the Danes, who possessed Nottingham. (Harl. Col. 368, 53.) As Ethelflaed died in 917, seven years before Edward came, the work of the famous lady in Bridgford looks very doubtful.

The name. We have still a difficulty as to the name. What was Bridgford called before there was a bridge? If the Saxons settled here about the year 600, and the bridge was built about 924, what was the name during that three hundred years? Had the place the same name before the bridge was built by Edward? Did a bridge then necessarily mean a raised road over water? Might it not have then included a paved road through a water? Traces of the early oak landing stage on the south side of the river were found in 1871 during the excavation for the foundation of the new bridge. In "British Place-Names in their Historical Setting," Mr. E. McClure, referring to another place, says, "Brige is evidently Briga—Burg or Stronghold," p. 113. "Brugeford," now called East Bridgford, was in the time of Domesday a much more important place than "Brigeforde," now called West Bridgford. There may have been, considering the importance of the passage to and from the Roman station at Margidunum, a wooden bridge at East Bridgford, but there are no traces of it, and had a bridge been built there it seems to be probable that it would have been as substantial as that at Cromwell, and it may be that both parts of the name then meant simply a road across a river. Why is the rock in the water at Filey called "Filey Brig? "All this is, of course, inconclusive, and must so remain. For certainty as to the then name we must wait uutil the Norman Conquest, for apparently the old name is lost.

The bridge itself is said to have consisted of stone piers, and oak beams or framing. It is not unlikely that the stone piers were built upon oak piles driven into the bed of the river. The oak beams would probably be cut from the Coppice Wood by St. Ann's Well, or from other parts of Sherwood Forest.

Domesday. After the Norman Conquest the Manor of Cliftun (Clifton), which had in Saxon times belonged to the Countess Gode, was given to William Peverel, the lord of Nottingham Castle, together with the villages that were subject to that Manor, and these included Bartone (Barton in Fabis), Wilesforde (Wilford), Brigeforde (West Bridgford), Alboltune (Adbolton), Basingfelt (Basingfield), Gamelstune (Gamston), and other places. The Countess Gode must not be mistaken for the Countess Godiva, the wife of Earl Godwin, who was lady of the Manor of Newark, and better known in connection with Coventry. The owner of Bridgford was, according to Dr. Bound, (Victoria History, p. 228) the wife of Earl Ralf, of Hereford, and apparently the gift of the cluster of places round the bridge was a part of a scheme for the protection of the road, and the castle of Nottingham. There is a special entry in Domesday book to the effect that " Over the soc which belongs to Cliftune, (which included Bridgford) the earl ought to have the third part of all customs, and services." As there was then no earl of Nottinghamshire, Dr. Round suggests that these dues may then have been in the King's hands. No value is attached to the entry as to Bridgford, but £16 is put as the value of the Clifton Manor, which sum probably included the value of all the places attached, for that sum would be a large one for Clifton only. (Multiply thirty times for present values).

In Brigeforde there was before the Conquest assessed to the geld, or for land tax purposes, twelve bovates (?180 acres). When the account was taken (1086) there was land cultivated sufficient for three ploughs. William Peverel had then half a plough (land or team) in demesne—that is, in his own hands belonging to his Manor farm. Three sochmen (ordinary farm tenants) would attend every three weeks at their lord's court at Clifton. Four villiens were tenants in a servile condition, who must work part of their time on their lord's manor farm in lieu of rent for the land they occupied. There were also two bordars (serfs who were liable to be transferred with the land). There was twelve acres of meadow, or common pasture. There was a priest and church at Clifton, and a priest at Wilford, who may possibly have served for several parishes, including Bridgford, but this is not likely.