Kinoulton's claims to note

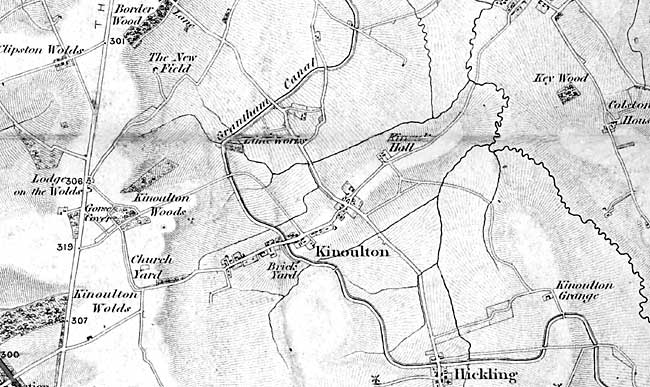

Kinoulton depicted on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey 1" to the mile map dating

from the 1840s.

Few parishes in the county can outrival Kinoulton in the extraordinary interest and variety of its claims to attention.

A notable legend attaches to its early days. Three lost villages existed within its bounds. Like the near-by Colston Basset and Rempstone it has deserted its original hilltop site and reshaped itself on lower grounds.

Ecclesiastically it was a "Peculiar," free of intervention alike by (the archdeacon and Southwell, its vicar having power to hold a civil court for the punishment of offences against his church, to grant marriage licences and to hold a probate court for proving the wills of his parishioners without the consent of other authority. It has had a castle; an episcopal palace has been claimed for it; a village school is noticed in mediaeval annals, and in more recent times it has boasted a spa and is reputed to have served as a local Gretna Green. So much for the menu, and now to the feast.

THE LEGEND.

The bridge over the Grantham Canal, Kinoulton.

In a field at a little distance from the church lay for untold ages, a huge granite-like boulder which, according to tradition, was thrown by the Devil from Lincoln Hill to destroy the sacred edifice which to his disgust he saw rising on Kinoulton Hill, but happily the missile fell a trifle short. Geologists concur with this theory so far as to describe it as an "erratic" boulder, the like of which they have found at road corners by Owthorpe, Hickling and elsewhere, but they unfeelingly account for them as having been brought hither by floes of melting ice of the Glacial Era.

This example may have been larger than usual, but it has long been broken up for building stone, mending roads or other profane use.

The legend was just a bit of folklore that could be matched in many parts of England, and it may be observed that no part of the shire is richer in field-names concerning dragons and the supernatural than the Vale of Belvoir. In virtue of its name, which is said to indicate the "tun" or farmstead of Cynehild, a woman. Saxon origin is ascribed to Kinoulton, which appears in Domesday as Chineltune."

It is one of the comparatively few villages having documentary evidence of existence of earlier than Norman date for a charter of 971 records the grant by Aernketel to Ramsey Abbey of lands in "Hikelinge et . . . Kinildeton" with the services belonging thereto.

The abbey is not credited by Domesday with lands or messuages in either of these parishes but Sir Frank Stenton points out that the grant was apparently of a customary rental "in which hams and cheeses formed a part.”

At the Conquest seven bovates of land and 20a. of meadow in Kinoulton supported nine sochmen and three bordars, and these were granted to Walmer de Aincurt. Azor, a thane, had one bovate and 3a. of meadow, which the Conqueror permitted Azor's son to hold. Its taxable value in 1087 had declined since the Conquest from 10s. to a mere 2s. 8d. No church is mentioned in the Survey and it is apparent that the village was then of little significance.

Newbold—now lost—was more considerable. One manor belonged to the Confessor from whom it was held by the famous Earl Morcar. Here was a priest and a church; it had 13 sochmen, 13 villeins and 3 bordars and its taxable value of £4 in 1066 had increased to £10 by 1086. Morcar had also a manor here assessed to the geld at 50s., and having soc in Lenton. The royal manor was retained by the Conqueror and the manor was granted by him to Wm. Peverel, Morcar probably having forfeited it by rebellion against William who had previously confirmed him in possession of it after receiving his submission.

According to some accounts the site of Newbold is to be identified with modern Kinoulton–a theory which Domesday does not support. Others hold that it was Colston Basset. Its latest contemporary records seem to have been in the reign of Henry III.

Nearly three centuries ago, Thoroton wrote that the last traces of it were well nigh lost, adding that it lay between Kinoulton and Colston Basset. What happened was perhaps that the inhabitants of these two hill-top villages came down to the decaying Newbold and absorbed it between them.

The late Rev. Evelyn Young, who studied the problem for his "History of Colston Basset," states that "the graveyard of the ancient parish church of Kinoulton may still be seen high up on the wolds, and the old chapel of Newbold was used as the parish church until the present church was erected in 1793." In Thoroton's time, the vicar of Colston Basset regarded himself as the parson, and Mr. Young (himself vicar of Colston Basset) added that "even now (1942) part of, the income of his benfice is derived from tithes in Kinoulton, and one piece of the vicar's glebe, known by the name of Gisburn. is in Kinoulton parish."

LODGE-ON-THE-WOLDS.

Another of Kinoulton's shadowy satellites is Lodge-on-the-Wolds, but, in this instance, the site is known, though it is doubtful if it ever achieved the status even of a hamlet. it was probably never anything: more than a lodge end a secluded wayside inn.

Allcroft's "Earthwork of England" informs us that "the name of Lodge Hill is of constant occurrence and seems likely to refer to the existence upon a hill-top of some kind of enclosure or building . . . often, probably, a hunter's lodge," a description of which physically applies here. In the 17th century, it was the property of the Hutchinsons, and witnessed stirring scenes during the Civil War.

GILBERTIAN.

It never had a chapel, nor was it attached to any parish church, and its modern state is of a truly Gilbertian character—as will presently appear.

KINOULTON CASTLE.

Shortly after the death of the Conqueror, Pagan de Vilers, of Crosby, in Lancashire, was also lord of Kinoulton holding it of the Butlers of Warrington, who gave their name to Cropwell Butler. As lords of this manor they made their residence here, being sometimes called "of Kinoulton" and at other times "of Newbold," and to them it belonged into the reign of Edward III.

The Vilers' seat appears to have been a defensive structure of the nature of a castle (not necessarily of stone), in which character it appears in records of 1151. Stephen's anarchical reign was then nearing its end. The Butler overlords of the Vilers fought under Randolph, Earl of Chester, on behalf of the future Henry II. The Earl of Leicester, who supported Stephen, had a castle in the not-far-distant Gotham, and the two warriors made a compact that neither should fortify his castle. Thus in all probability, Kinoulton was spared the terrors of a siege: the castle is heard of no more.

WARBERGE.

Of Warberge, the last of Kinoulton's lost villages, little is known. In 1066, it had two manors, together rated to the geld at only 10s., but by 1087 their value had dwindled by half, and the Domesday clerks noting that here were 10 acres of meadow, described the rest of the land as waste, and recorded that it had been granted to Roger de Busli.

Thoroton found that this hamlet had so utterly decayed that he sought in vain for traces of it. It lay towards Plumtree, but was accounted part of this parish. Possibly the "Warborough Grange," "otherwise Plumtree Grange or Normanton Grange," mentioned in the records of Haverholme Priory in 1540. may indicate its site. Potter's "Tollerton" states that "Warby Gate" in that parish was "the old road to Warborough, now merged in Cotgrave Lane," and it seems possible that these two names relate to Warberge.

DESTROYED AT KING'S COMMAND.

It may have been during Henry's visit to England as Duke of Normandy in 1149-50 that he granted Peverel's great fee, including a manor here, to Ranulph, Earl of Chester, unless Peverel could clear himself of some "wickedness and treason."

To this grant attached the condition that the earl must conquer the extensive fee ere he could enter upon it and according to the old chroniclers William took effective steps to prevent this by causing Randolph to be poisoned. In 1153, the war was terminated by the Treaty of Wallington, which provided that Stephen should retain the crown for life and that Henry should succeed him upon the throne. In the following year, Stephen died and Henry, as king, demanded the destruction of all unlicensed castles and the surrender of such royal fortresses as were held by his opponents. Kinoulton Castle was then probably destroyed or dismantled, but the royal castle at Nottingham was in possession of Peverel who refused to cede it.

JOHN'S FIRST INDISCRETION

As Henry marched to capture it, Peverel sought safety by assuming the tonsure and cowl of a monk in Lenton Priory, but as Henry advanced he fled and his fate is unknown. The king seized Nottingham Castle and the forfeited fee which, in 1174, he granted to his youngest son, John. In 1199, John usurped the throne and committed his first regal irregularity by surmised of a grant by its Peverel imposing a coronation levy to which Kinoulton was assessed. Under the Normans, Kinoulton developed, and, in 1171, was paying well above the average amount of parishes in the deanery of Bingham to the Pentecostal offering at Southwell. By exchange of lands, the Fanecourts acquired the Deyncourt interests here and at the close of the 12th century, they and the Vilers were the two outstanding lay owners, but the inconsiderable share of the parish was passing into ecclesastical possession.

The first monastery to gain a local footing was Blyth Priory, to which its founder, Roger de Busli, gave his Warberge tithes by 1088. In 1316 Lenton Priory was certified as one of Kinoulton's lords in virtue, it may be ?founder. In 1121, Ralph Basset, Chief Justice, bestowed property at Newbold upon Evesham Abbey, and about 1163, Swineshead Abbey received a gift of land from Elias de Fanecourt with more from William de Vilers.

About 1189, Pagan de Vilers made over to the Archbishop of York and his successors the church at Newbold with lands, &c., which the prelate promptly leased out at 48 marks a year in aid of his fund for hospitality.

One of the Fanecourts granted a capital messuage, demesne lands, a windmill, fishponds and manorial rights in Hickling and Kinoulton to Thurgarton Priory.

Subsequently, a prior of Thurgarton granted these back in return for 18s. a year in silver, but meanwhile the Vilers obtained licence to have a chantry in the chapel of their mansion at Kinoulton, subject to the usual condition that the principal feasts be observed in the parish church of Newbold.

In 1264, it was found that the vicar's stipend consisted of the small tithes, oblations and obventions of the altar, in wool, lambs, mortuaries, tithe of mills, a mediety of the tithes of hay, arising out of the right of the York Chapter, Peter's pence, and 20 marks yearly of the archbishop or farmer of the church. As things then went the vicar was doing well.

Alexander de Vilers, lord of Kinoulton (who may fill a gap in Thoroton's list) was a crusader who incorporated the crusaders' badge in his coat of arms. He was with Prince Edward in the Holy Land when Henry III died in 1272, and it is not improbable that he had some of his tenantry in his train. The days of the Vilers as local lords were then drawing to an end, and it may be that the grant by William de Vilers of a messuage and ten bovates of land to Ralph Bugge in 1280 was the ominous shadow of coming events.

The grand was made in return for a rental of 1lb. of pepper and some cummin, and was doubtless the extinction of a previously contracted debt to the woolstapler Bugge, the founder of the families of Willoughby and Bingham, which could not otherwise be cleared. In Sir Pagan (or Payn) de Vilers acknowledged a debt of £100 to Roger Beler and Rd. de Whatton and ten years later he was owing £180 to Ralph Basset. In 1335 he passed his Woodborough manor to Rd. de Strelley, he was the last of his line at Kinoulton, and the homestead most of which traces remain may have encircled his abode.

UNWELCOME RIVALRY.

The registers of Archbishop Romeyn disclose the existence of a school here in 1289, and reveal that it was then of ancient date. The "schoolmaster of Nottingham," had protested against its rivalry, for it was attracting outsiders, to his disadvantage, the prelate decreed that in future "only the clerks of the parish might attend the school which had from ancient times been customarily kept in this parish all other clerks and ... [missing].