Haughton to the verge of its splendour

The remains of the north arcade of St James' chapel, Haughton (photo: A Nicholson, 1982).

Although it is true that Haughton now ranks as one of the diminished villages of the county and that its great days were limited to about a century-and-a-half when the opulent family of Holles were its resident lords, it has an interest distinctively its own and some historic ruins, fortunately well preserved.

NO vestiges of remote antiquity are associated with the parish, and the history of its early days is a matter of speculation. It was established in a sequestered situation five miles distant from Tuxford through which passed the track which was to develop into the Great North Road, but whether the invading Saxons approached the village site from that highway or penetrated inland from the Trent by rowing along the Idle can only be guessed at. The origin and meaning of the name is similarly indeterminate. Its earliest known form is "Hocton," thought to be a compound of "Hoh"—the Old English for a heel or projecting ridge of land, and the familiar "ton" from which our "town" derives, and a variant form of the prefix is "haugh." The personal name of Hoc has been suggested for the fore-part, while the O.E. "halh," which indicates a flat meadow by a riverside, seems appropriate until it is remembered that the vowel "a." does not appear in the name till the 14th century, previous spellings of the name invariably having an "o." Inasmuch as Domesday mentions a church here, and as "Hoctun" was taxed to the geld at 60s., it was a fairly valuable part of the grant the Conqueror made to his follower Roger de Poitou, but by 1086 its value had fallen to 20s. It may not be without significance that many of Roger's other manors in Notts, had similarly declined, and the great survey records of Haughton's soc in Walesby that "It is waste." The Norman owners repaired or rebuilt the Saxon church, and in 1191 it was, as part of the Chapelry of Blyth, given by the future King John to Rouen Cathedral. By that time the Matterseys had lands, Ranulph de Mattersey bestowing a meadow upon his son "Robert the carpenter," and his son Ralph, giving some land here "with all the water of the Yddil" (Idle) to Rufford Abbey.

In 1258 the church was constituted a rectory annexed to the vicarage of Walesby, whose parson was to have the great tithes. It was ordained that he should understand English and cause the church (a chapel) to be honestly served, and he shared with the Chapter of Rouen in the charges for the maintenance of the building and the provision of books, vestments and other appointments of the altar. In 1470 the Bishop of Dromore was licensed to consecrate this Chapel of St. James—which may then have been partly rebuilt—of which some interesting ruins still remain.

By the close of the 13th Century, "Hoghton" pertained to the Duchy of Lancaster of which it was held with many other properties by the Matterseys by rendering homage and suit at the Bothamsall court every three weeks and contributing 20s. yearly towards the guard of Lancaster Castle and paying 8s. common fine. In 1316 Bothamsall and Haughton formed one official vill and Thomas Earl of Lancaster was its overlord, but in 1322 the earl, after checking the evil career of Edward II. was captured and beheaded, but the rights then forfeited were soon restored to his brother at whose death they were granted by Edward III to his son John of Gaunt, Shakespeare's "time-honoured Lancaster " and his wife Blanche, who was Chaucer's patron.

The Matterseys still held land of the vill but in 1298 the manor had descended to the Chauncys to pass by 1352 by an heiress of that line to the Monboucher family. At that period John de Longvillers had here two messuages with half-a-caracute of land, 10 acres of meadow and two watermills, for all of which he rendered a rose yearly to Nicholas Monboucher. In 1384 the widow of Sir Nicholas Monboucher was possessed of "the manor of Hoghton upon Idell and a wood there called Lound," but shortly after that date the manor was in the hands of John de Longvillers, the village becoming known as Haughton Longvillers, on account of this connection, to distinguish it from Hawton near Newark.

QUESTION OVER AN HEIR.

John de Longvillers was succeeded by his brother Thomas whose daughter carried the manor by marriage to Robert Maulovel of Rampton, and by the marriage of their grand-daughter it was conveyed to John Stanhope, the son and heir of a Newcastle burgess of note, the progenitor of the famous race of Stanhopes destined to become Earls of Chesterfield.

The Stanhopes quickly increased their Haughton possessions. By marriage to the sister and co-heiress of John de Longvillers Sir Reginald de Everingham of Laxton received a portion of this village and his death without issue raised a difficult point as to the next right heir, a legal enquiry awarding the disputed share to Richard Stanhope.

It would almost seem that in the 15th century the manor was divided, for though it is generally understood that the lordship was held by the Stanhopes throughout that period yet contemporary records tell that in 1417 Matilda de Kevermond, "the last of the Monbouchers," settled the Monboucher manor here upon William Foljambe and others, and in 1464 Margaret Cokefield held that manor for life with reversion to Thomas Thurland. In 1493 it was returned by a jury that "Hoghton" Manor was held by John Stanhope from the heir of the Monbouchers and it is supposed that it was this John who built the Hall of which the tower long displayed his arms.

FROM STANHOPE TO HOLLES.

Although the Stanhopes took an active part in the Wars of the Roses, they appear to have remained in possession of their manors unmolested of account of their adherence to the Lancastrian cause. There are no records of the forfeiture; of their properties though a debt due to Henry VII may possibly refer to an unpaid fine imposed by the victorious Edward IV. Richard Stanhope who fought for Henry VI lived well into the reign of King Edward and his son and heir attended that monarch as a personal attendant in his war with France. In 1487 Edward Stanhope was one of the commanders at the battle of Stoke which settled the Tudors on their throne, and ten years later he and his archer retainers fought with such distinction at Blackheath, where the Cornish rebels were crushed, that he was knighted on the battlefield.

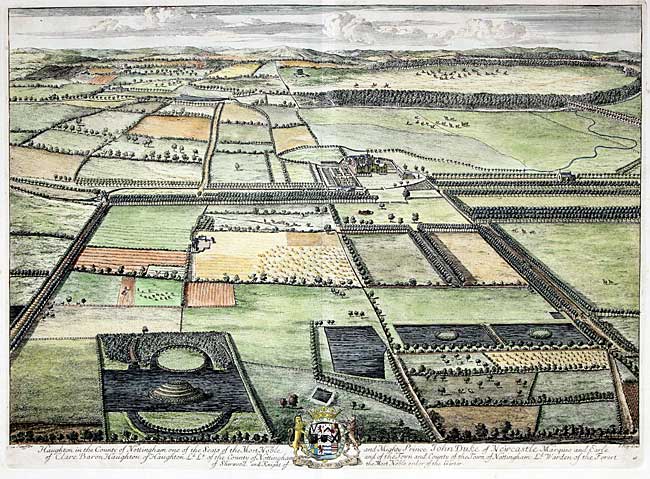

Perspective view of Haughton Hall and Park by Knuyff and Kip, 1709.

It was this warrior who in 1509 enclosed 200 acres of his pastures and 40 acres of arable land to form a lordly park. Land enclosures were then giving rise to such concern that a commission was appointed to investigate the matter. Its report with regard, to Haughton was that, the land so imparked was fit for tillage, but that Sir Edward "keeps it for rearing wild animals." The animals would be deer and it is not improbable that some depopulation resulted through soil falling out of cultivation, labourers being rendered workless and their domiciles destroyed. The inhabitants, probably never very numerous, numbered in 1676 only about 70, including children.

DIED AT THE BLOCK.

Whether Sir Edward Stanhope was encumbered by an Edwardian fine or had overtaxed his resources by enlarging the Hall, or in other ways, is not certain but in 1506 Henry VII, being seized of this and other manor of his, granted them to him to farm out for 15 years at £40 a year to Dame Katherine Ratclyff and £70 per annum thereafter "until his debt of £600 to the King is fully satisfied." This lord of Haughton died in 1511 leaving two sons—Richard and Michael—of whom the latter purchased Shelford, etc.. upon the suppression of its priory and in 1652 shared in the ruin of his relative, the Protector Duke of Somerset, and, like him, perished at the block. Haughton fell to his elder brother Richard, whose only child, Saunchia, a great heiress, wedded John Babington and from them the manor was purchased by Sir William Holles who had amassed a considerable fortune in London, it is said as a baker. He was probably a wool-stapler.

Leland, writing at that time, observed that all over the kingdom there were springing up those handsome dwellings which later generations have known as "gentlemen's seats." Every considerable landowner had his "paled park," and as a result of the increased wealth following upon the Renaissance, citizens who had accumulated fortunes were throughout the realm purchasing properties and settling down in the country as local magnates. It was a policy approved by the Tudors as a counterpoise to the old and often rebellious baronage, and Sir William Holles, having been an alderman and Lord Mayor of London, followed the fashion. Possibly the "paled park" attracted him; in any event he acquired the hall and manor with many other local estates, and his coming heralded the great days of Haughton.