< Previous

Bothamsall has great historic interest

By W.E.D.

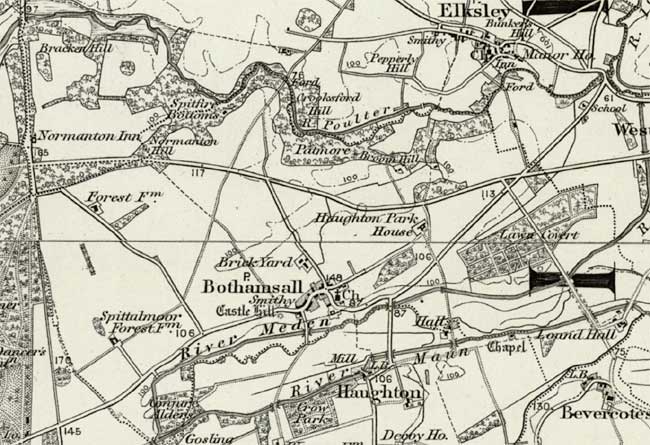

Bothamsall parish in 1899.

Bothamsall parish in 1899.THE parish of Bothamsall has great historic interest. A yet flowing well in the centre of the village is said to be “the spring of the bottom of the valley” from which, ages ago, the place derived its name, though other theories suggest that it means the nook or hall of an unknown Bothelm or some other similar personal name.

Its origin is lost in the mists of antiquity. Mounds by the wayside west of the little village tell of earthworks probably of Celtic construction more than 2,000 years ego, and the discovery of Roman coins may indicate that they were utilised by the Romans. Castle Hill preserves the memory of a Norman stronghold on the site. Lying near the Maun and the Meden on the confines of Sherwood Forest it must have been largely marsh and woodlands in early times, and the first comers chose for their purpose a hillslope and hewed down timber with which they built their huts and a protective stockade.

A Turbulent Earl.

In 1066 its lord was the turbulent Earl Tosti of Northumbria, Harold’s brother, whose support of Harold Hardrada drew the last of the Saxon kings north at a critical juncture with possibly decisive results to English history. Tosti was slain at Stamford Bridge, and when the conquering William parcelled out his new territory he retained Bothamsall for himself, making it one of the five royal manors of the shire— the others being Mansfield (chief of them all), Arnold, Dunham, and Orston, and to this manor were attached lands at Babworth, Elkesley, Normanton, Ranby and elsewhere.

Domesday mentions no church, but there was a mill, 40 acres of valuable meadow, arable land enough for two ploughs, and a population of five villeins and one bordar and their families. To the manorial court here came for centuries those who held lands pertaining to Bothamsall, the reeve of the overlord receiving the dues and preserving all superior rights. Before the Conquest it was valued at £8, but by 1086 this had declined to 60s. Being the king’s property may account for this low figure, but another possible explanation may be advanced.

Bothamsall Castle c.1931.

Bothamsall Castle c.1931.When or why or by whom the castle was built are alike unknown, but it is clear that it was of Norman, type. Mr. Blagg, who investigated the site some years ago, found that its circumference was about 70 yards, with a parapet 70 yards in circumference and 20 yards diameter crowing the top. There is a glacis or sloping bank to the marshes of the Meden below; remains of the moat are still visible, and the high road intersects the bailey or court. He was of opinion that it was a “motte (mound) and bailey” castle of the 11th century, erected to hold down the neighbourhood, and “abandoned when the occupation of the country became more assured.” This is probable enough, for as the king was the sole owner of the manor it could have been raised only by his command, though it may have been built during the anarchy of Stephen’s reign to protect Bothamsall and its berewicks.

Like Nottingham Castle, though on a much smaller scale, it was perched high, and, whenever it was made, it seems probable that the Meden (which flows, as the Leen did at Nottingham, in an artificial channel) was then diverted to strengthen its defences. It is tempting to think that this castle was created about 1068 when William was subduing the district, for Notts, did not readily, submit to him, and his harrying, hereabouts may account for the notably diminished value of the manor at the end of his reign.

The Lady Of Tickhill.

The village grew slowly, for when the Pentecostal offerings at Southwell were instituted in 1171 its yearly contribution was but 10d., and a return of 1325 showed only seven villeins and four bordars. By that time the royal hand had relaxed its local grasp, and the Countess of Augi, as Lady of Tickhill, held the manor from the Crown, and a chapel, owning Elkesley as its mother church, had been erected. The St. Georges and Furnells were established as the local lords, the lands pertaining to the Honour of Lancaster, of which Tickhill was the local head. Near the close of the 12th century Richard de Furnell quitclaimed to Welbeck Abbey his interest in the chapel here. It appears to have been originally a free manorial chapel, founded within the parish of Elkesley, and if not of older foundation it may have been built by one of the manorial lords, perhaps Robert de Furnell, who was a benefactor to Rufford Abbey and Worksop Priory.

The vicar had for his maintenance its altarages, reserving to the rector of Elkesley only the tithes of corn and hay and the demesne lands belonging to the church. The patronage was held by Welbeck Abbey, which was apt to appoint one or other of its monks to serve the cure. John Wentbrygg, sacrist at the abbey, was its vicar or chaplain from 1488 to 1500, and in 1494 he was censured for the irregular cut of his tonsure : in 1500 he was notorious for his disorderly life and the multitude of debts which he made no attempt to deny. He undertook to reform, but as he ceased to function here in that year he was probably replaced by a more respectable priest.

The St. Georges.

An inquisition of 1244-5 found that Robert de St. George had held 2½ caracutes of land in the vill and soke of “Bodmeshill,” with a water-mill and a fishery. He had a capital messuage or manor-house, and his reeve occupied half an oxgang (15 acres) of arable land and a patch of meadow. He had to plough in winter and Lent, mow, carry, and stack hay, and do a day’s weeding for his master every year, give help at Michaelmas worth 3s., pay one hen each Christmas, and take his part in repairing the mill-dam when required. Nine villeins and two cottars held smaller lots in the soke by similar but lesser services and there were freeholders, among them a William de Boulli who may have been a descendant of the Norman Roger de Busli.

The northern boundary of Sherwood Forest ran hereabouts along the line of the Wollen, and at Coningeswath ford at Conjure Alders, where a bridge now carries a road across the Maun, many of the forest perambulations began and terminated. The adjacent parks and woods of Clumber, Thoresby, and Haughton are reminders of the picturesque times of Robin Hood.

Near the close of the 13th century the St. Georges faded out, and in 1397 Richard de Furneus (Furnell) and Rd. de Boselingthorpe held most of the manor of the Honour of Lancaster, doing homage at its court here and rendering 10s. for the watch and ward, of Lancaster Castle and paying each 4s. a year. The value of the manor was then £20 per annum, and as it was held by knight service the two lords had to render corresponding military aid whenever required. Outlying parts of the old royal manor also belonged to this Honour and were held by divers persons under similar feudal tenure, making their homage and suits and paying their dues at the Bothamsall court every three weeks. In 1322 affairs would be somewhat dislocated when the Earl of Lancaster was executed as a traitor and his possessions confiscated, but after being in the hands of John of Gaunt for a few years they were restored to the late owner's brother.

A Furnell Heiress.

Soon after this time the Furnell moiety of the manor passed to Thomas Latimer. He died in 1355, leaving, as his heir Henry de Ravenswath, whose father had wedded a Furnell heiress, and was the last of his line. Thomas did not long retain this part of his inheritance; for in 1386 it passed to Henry FitzHugh. Fourteen years later John de Markham obtained the other moiety, and with its descendants it remained until the reign of Elizabeth. The Markham tenantry may have followed their lord to fight for Edward IV in 1461 at Towton, and in 1487, when Henry VII was nearing Stoke to crush the Simnel rebellion. Sir John Markham led out his retainers to support him. Upon the accession of Edward IV the Duchy of Lancaster was forfeited to the Crown; but Bothamsall was terra regis for only a brief period. It reverted to the Duchy, but in 1487 it was found by a jury that Sir Richard FitzHugh had recently died seized of the manor of which no part was held of the king in chief.

Bothamsall under Tudors, Stuarts, and The Georges

LAPSE of Crown rights was not the only important local change under the Tudors, for the Reformation wrought a distribution of monastic properties here as elsewhere. Rufford’s possessions, including a grange at Foxholes, were granted to the Earl of Shrewsbury. What Welbeck had was sold, with the abbey itself, to Richard Whalley, who secured remission of the £4 a year it had paid to the parish priest. To the Earl of Bedford went a plot of land and a meadow called “Priour’s Dole,” which had belonged to Worksop; even a tiny plot of ground which some pious donor had given to maintain a lamp in the church was seized and sold, and under Elizabeth the rectorial rights were sold to Sir John Holles, ancestor of the Dukes of Newcastle, who became sole owners in the parish. Meanwhile, the parish church was being neglected, and in 1559 its chancel was reported to be “far in decay.”

About 1565 the Markham property here was sold to that enterprising speculator, William Swift, their late owner, whom Thoroton dubbed “the fatal unthrift and destroyer of this eminent family,” having so wasted his substance at Court that all his estates had to be sold. The “Good Sir William” Holles, who died in 1591, directed in his will that “Robert Kirkby, now keeper of my park (of Haughton, adjoining Bothamsall) shall have his office during his lifetime after the same manner and order as he now hath it, and also his house and other the grounds which he now dwelleth in at Bothamsall, in as large and ample manner as he now hath and occupies the same, behaving himself and doing his service unto my heir justly and truly as he hath heretofore done unto me.”

Tudor Lawsuits.

The provision thus made was prudent, as the heir was a grandson, John, who in 1597 was convicted in the Star Chamber for extortion from his tenants and encroachments of the public ways. With the Tudors set in the inevitable lawsuits respecting property, but only one or two call for mention. Swift’s acquisitions did not pass unchallenged; his manor, with its appurtenances, was claimed against him in 1565, but he successfully called Robert Markham to prove his title and remained in possession. He died in 1568, his son was knighted and his grandson became Viscount Carlingford. The various members of the Elwyse family mentioned by Thoroton as litigants were of the Helwys family so prominently associated with the Pilgrim Father movement and their various suits were concerned partly with Lound Hall.

In 1600 occurred an instance of the old custom known as Borough English, to which Notts, was more partial than most other counties, and clung to somewhat tenaciously. Katherine Short in that year willed her grange at Normanton, partly in this parish, with its lands in Bothamsall to her youngest son (and son-in-law), leaving small bequests to her elder children, but they were not to benefit thereby until the favoured heir had been in peaceable possession for two years. The disinherited seniors contested the will, but how it was determined the record does not state. In 1612 the chief owners in the villages of Elkesley and Bothamsall were Sir Robert Swift, the son of Barnabas Williamson, John Marnham, John Beardsall, Robert Brett and several Sharpes, the Williamson portion being that formerly of the FitzHughs’, in cluding Lound Hall.

Under James I.

At the accession of James I there were 24 adult inhabitants with a probable total population of about 100, including children. The vicar returned that they were all orthodox and that there were no recusants, but he probably turned a blind eye upon some of his flock, for in 1516 one Wm. Aldridge of this parish was committed to the assizes as “a Popish recusant who came not to church for nine months past, and receiving books from Roger Bown, lately seduced from the religion established by God in England, to the Romish religion.” Other residents were cited to the courts for adherence to the old religion in the time of Charles I. In 1673 the curate (John Melson) reported 104 inhabitants and that there were none who habitually absented themselves from the church services or refused the Communion. Sixty-seven years later another curate (Wm. Boawre) stated that “there are 28 families, in my Parish; not any of ’em Dissenters, that I know of.”

There was a school here in Elizabethan times, for in 1583 it was recorded that “Martin Thackerory the Scholmaster of Bothemsall ys dismyssed from the schole and (is) to have a lycence to serve as Curat at Walsby.” It may have been the memory of this that in 1688 inspired Henry Walter, steward to the Earl of Clare at Haughton, to found and endow a grammar school in which children of Haughton, Bothamsall, &c., were to be taught reading, writing and “what the master could manage of grammar” until they reached the age of 14. The testator’s intention seems to have been that the school should be at

Bothamsall for he made provision for a feast to be held here every year when the accounts were examined, but the earl gave a site just outside the gates of Haughton Park, and in 1692 was erected the building, which still exists. Walter, who left other charities, was buried at Bothamsall, where for a century, a vestry has covered his grave.

Great Changes.

In 1690 the Earl of Clare married the heiress of the 2nd Duke of Newcastle, and removing to Welbeck left Haughton Hall to decay. He succeeded to the dukedom, and in 1709 had licence to make Clumber Park and include within its bounds “part of Bothamsall alias Normanton.” He also acquired land in Bothamsall from John White, of Tuxford, and his successors in the title continued to acquire properties until the whole parish belonged to them.

In 1743 the then duke was allowing “only £20” a year to the curate, but for this stipend the curate (who also served Kirton and resided there) held divine service every Sunday afternoon except on the last Sunday in each month, when service was held in the morning and at Kirton on that afternoon. The churchwardens of that time were Wm. Wood and Edward Winch.

Great changes in the appearance of the parish took place in the reign of George III. Owning most of its territory the Duke of Newcastle about 1770 began to develop it, and by 1798 had enclosed upwards of 1,000 acres, planting woods and fostering the culture of hops. At Apley Head he clothed 349 acres with trees, and created spinneys of various sizes at Peck’s Farm, Dewick’s Farm, Broom Plantation at Moss’s Farm, Fivethorns Plantation, another on the hill above Ousedale “from Padley’s watering-place (for cattle) to the Normanton coach road gate,” and various others. Some were small, but at Patmour he planted 41 acres and at Crookford 14 acres.

Other waste was turned to cultivation and a series of fields hedged with quickthorn or posts and rails from the thinnings of Clumber Park adorned the landscape and provided labour. The village throve. In 1793 its inhabitants numbered 212, but some of the land was recalcitrant: among the local fieldnames Pining Wong tells of a clearing that refused to become productive. New England is a nickname for an outlying part. In 1797 Throsby scornfully described Lound Hall as “having nothing striking either with respect to magnitude or elegance . . . occupied by what the world now fashionably denominates “a gentleman grazier.”

The Churches.

Bothamsall church from the south-east in 2005. © Copyright Richard Croft and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Bothamsall church from the south-east in 2005. © Copyright Richard Croft and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.The church is variously said to be dedicated to St. Peter and St. Mary, but the fact that the feast was held on the Sunday nearest St. Peter’s Day is proof presumptive that the former was the old name. It was the burial place of the Newcastles, but a hundred years ago it was dilapidated, and the duke thought of restoring it. In 1817 a Norwich architect was called in to advise, and materials for the restoration were collected, but at the last moment the plans were changed and the material went to make a new church at Markham Clinton and a new family mausoleum there, to which the remains of dead and gone Holles were removed. In 1844 the duke erected the present handsome edifice there, largely with stone brought from Worksop Manor, where he had recently purchased the estate and pulled down the great mansion.

The church has therefore no antiquity, but it preserves the font of its predecessor, the paten given by Henry Walter, three old bells, and its register is one of the very earliest, dating from 1538, the year when the keeping of such parish registers were established by law. In 1884 Lound Hall, formerly included in the parish of Gamston, was transferred to that of Bothamsall, and in 1910, when a railway from Ollerton to Retford was projected, this village was scheduled for a station, but the scheme fell through. It is curious that in 1801 the inhabitants numbered 235, and that after steadily climbing to 319 in 1851, an equally steady decline set in, and the census of 1901 showed precisely the same number as that of a century earlier. In 1931 the population was 238.

< Previous