Vicissitudes and romance of Bole

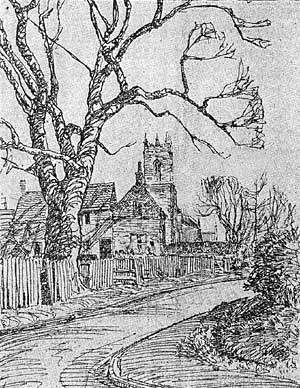

THE little village of Bole, distant one mile from the Trent, almost opposite Gainsborough, has received but little attention from local historians. Thoroton devoted a few lines to it and his successors have not added much to his account, while others have altogether ignored it. Yet, it has not been without strange vicissitudes or romance.

Its early history is unknown; its name is not illuminating and guesses at its meaning have confused rather than cleared the issue. A bole or tree-trunk, a smooth rounded hill, a plank bridge or a dwelling-house have all been advanced as explanations, and perhaps the first is the most probable solution. “Bole” is a Saxon word, and the latest theory is that Saxon marauders here found some elevated ground rising out of the environing morass and made their abode amid the trees. That the village existed before the Norman Conquest is certain, for the Domesday record notes its church, but the rest of the entry in that survey presents a problem for its Compilers mixed up Bole with Bolham under the name of Bolun, and, as Thoroton found, it is difficult always to distinguish to which of the two villages the details relate.

It tells us that “Bolun” then had two mills—of which one was almost certainly at Bolham—meadows a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide and a much larger wood, and the 17 socmen and bordars may have represented a population of 70 or so. Torvert, who was lord of Bolham held land in “Bolun” where Ulmer had a manor, but at the Conquest both places passed to Roger de Busli, who retained part for his own purposes and installed one Geoffrey as his “man” or reeve to protect his interests.

Hubert De Burgh.

The Busli family soon died out, but before that time many of their estates passed to the Lovetots, and when (about 1130) Wm. de Lovetot founded Worksop Priory he gave as part of its endowment “the mill of Bole with the waste of Aspley and all the grain as it is enclosed by the foss, namely 100a. of waste with one measure of an acre beyond the. foss.” The church belonged to the Archbishopric of York, and for long ages the prebendary of Bole in that minster has been one of the chief owners of the parish wherein he exercised manorial rights. The Duchy of Lancaster had possessions here as of its Honour of Tickhill, which later passed to the Crown, and Bole was in various ways associated with Saundby and Scrooby and the archbishops’ great soc of Laneham.

One of the most distinguished of local proprietors was the great justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, who, as Earl of Kent, was virtual ruler of England following upon the death of King John. In 1278 Philip de Boulton, surgeon, released to Edward I his yearly rent of ten marks here which he had by the gift of the then Earl of Kent, a lineal descendant of the justiciar. In 1379 John of Gaunt (Shakespeare’s “Time-honoured Lancaster”) charged Sir Philip Darcy with ravaging his property at Bole. Darcy had accused men of this parish of breaking into his close at West Burton, taking game in his warren and destroying his corn. It was apparently a common poaching affray and, taking the law into his own hands, he had mustered a party of knightly friends and retaliated by attacking the village.

Some of its inhabitants were beaten, some compelled to pay money or have their goods taken, and many were so terrified that they fled into the woods. As the Duke of Lancaster was uncle to the king he would doubtless obtain redress.

Hotspur Plot.

Shakespeare’s “King Henry the Fourth,” Part I, Act 3, depicts the rebel leaders, Hotspur, Mortimer and Glendower studying a map upon which they had sketched out a division of the kingdom between them when they had overcome the king. The southern part from Trent to Severn was to go to Mortimer, Earl of March, that west of the Severn was to be Glendower’s, and the northward remnant, lying off from Trent was to be the fiery Percy’s portion. But Hotspur demurred:

Methinks my moiety, north from Burton here,

In quantity equals not one of yours.

See how this river comes me cranking in,

And outs me from the best of all my land

A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out.

I’ll have the current in this, place damm’d up.

And here the smug and silver Trent shall run

In a new channel, fair and evenly:

It shall not wind with such a deep indent

To rob me of so rich a bottom here.

The Trent between West Burton and Bole now flows in a straight line, but the ordnance map shows the dried up bed of the river which once ran in two ‘‘huge half-moons” between the two villages, and the passage above quoted is generally understood to refer to them. The description fits them exactly, but a claim has been put forward, on behalf of a somewhat similar meandering near Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire. In any event, the discussion was a case of counting chickens before they were hatched, for the battle of Shrewsbury (1402), in which some famous men of Notts. fought and fell, was fatal to the conspiracy, and “Harry Hotspur” was among the slain.

Nearly four centuries later the Trent adopted Percy’s proposal when, in 1792, it ignored “Bole Round” and straightened its its course to Burton where a year or two later the “half-moon’’ suffered a similar fate. The channel then made included land in Lincolnshire which is now reckoned to be in Notts.

The famous pluralist, Thomas Haxey, who after being rector of Laxton included among his preferments the prebends of Barnby, Farndon-cum-Balderton and Rampton; who was also treasurer of York Cathedral and the reputed builder of the chantry-priests’ house at Southwell, in 1415 founded in the minster there a chantry and endowed it with properties in Bole. He had an adventurous career, having been sentenced to death in 1398 for recommending economy to the luxurious Richard II. Another parcel of local land passed to the Church in 1398, Richard Rothwell then giving 8a. of land and 6a. of pasture tor the augmentation of the vicar’s stipend.

The Patent Rolls of 1474 reveal that Robert Marshall, a husbandman, of Bole, had been outlawed in connection with a perjury case. He had surrendered himself at the Fleet Prison in London, and now was pardoned, but in 1482 he again figured in legal records, when order was issued for his goods to be distrained upon for nonpayment, of his share of the parish contribution for the maintenance of the lengthy Leen Bridge at Nottingham. of which part was kept in repair by the county.

Lean Times.

Early in Tudor days the village fell on evil days. The great woolstaplers required more wool, and local land-owners were laying down arable lands to pasturage for sheep. The practice was becoming common, and the Crown issued edict after edict to check it on the ground that it depopulated districts and wrought desolation and ruin. In 1504 three freeholders here were charged with disobeying the statutes by “enclosing arable and ceasing to grow grain thereon,” and a transcript of the evidence was forwarded to the Exchequer in order that effective action might be taken.'

Chancery Rolls disclose that during the 15th, 16th, and early 17th centuries there were more than the accustomed number of lawsuits for a village of the size of Bole, but few of them are of interest. One of about 1440 was a dispute between members of the family of Thurston, which gave its name to a local meadow, and a case of 1535 resulted in Oliver Shaw, vicar of Markham, being compelled to deliver title-deeds to John Dressy, clerk. Lascelles, Babington, Nightingale, Hamerton, and Bland are some of the names of persons concerned in these litigations, and among others occurs the curious surname of Coswynsoswys.