< Previous

NOTTS. VILLAGES

Unusual Origin And Lively Times Of Bingham

By W.E.D.

The market place in Bingham, c.1910.

The market place in Bingham, c.1910.BINGHAM’S history presents two unusual features: the ground upon which it stands was once a lake, and the present township is said to occupy a site other than that upon which it was originally built. Geological experts agree that the alluvial flat known as Bingham Moors was once an extensive mere created by the melting ice of the Glacial Era, now represented by a peaty loam beneath whose surface is a mass of white shell marl or grey shelly clay.

The little hill (on the Scarrington side) upon which stands Holme Farm was an island standing out of the lake which has drained off and silted up. Wiverton Hall was erected on a similar island. The lost village stood a few hundred yards east of the present Bingham, in and about Crow Close, where Mr. Allcroft found no difficulty in tracing “with unusual ease in the grassy surface its narrow lanes and walls and foundations" so precisely that in his “Earthwork of England” he gives a plan of its layout. It was, he says, a mediaeval village, said to have been destroyed by a hurricane.

Ancient Origins.

The origin and meaning of the word Bingham are an unsolved problem of local nomenclature, and whether it arose from a “hollow among hills,” a “heap,” a tribe or a person of some such name as Benning is a mystery. “Ham” means an enclosed homestead, usually associated with some personal name, but beyond this it is unsafe in the present state of knowledge to venture. The discovery of Neolithic flint implements denotes the presence of man here several thousand years before the Christian era. In Ancient British

times this vicinity formed a central part of the territory of the Coritani tribe, and Dr, Adrian Oswald has recently found on Mill Hill an unrecorded mound that he conjectures may be the tumulus (burial place) which Stukeley said, two centuries ago, existed on “an eminence beyond Bingham land.”

When the Romans constructed the Fosseway as their great military frontier road they passed by the site of this village, and if the Samian ware said to have been found in Bingham really relates to the neighbouring Margidunum (E. Bridgford) the probability of the existence of any sort of Roman settlement here is considerably reduced, though the road, as the main artery between Leicester and Lincoln in ancient and later times, has been the making of historic Bingham.

In pre-Norman days the village was the head of the division of the county known as the Bingham Wapentake or Hundred, and in an amphitheatre on the “top of the hill near the most westerly corner of Bingham Lordship,” near the Fosseway, folk from every manor in the Hundred made compulsory attendance at frequent intervals from Danish times onward for the regulation of affairs beyond the jurisdiction of the manorial courts and not

sufficiently important to demand the attention of the shire moot. An Act of 1351 transferred many of the functions of the hundred moot to the Quarter Sessions, but the court in its attenuated form continued to function for centuries and in 1677 Thoroton wrote that “it meets, or ought to sit, in the Moot House Pit, though I think they usually move to Cropwell Butler as the nearest town for shelter.”

Land Reclamation.

By 1066 much land had been reclaimed from the swamps and its soil was so fertile that the parish was assessed to the Geld at the high figure of £10. Domesday records no church though there perhaps was one for the sochmen, villeins and bordars who with their families numbered over 200. There had been three manors, one large, held by Tosti, and two small ones belonging to Hoge and Helga. All went to Roger de Busli who, when founding Blyth Priory in 1088, gave it two parts of the tithe of the Hall “for the building of the place and the victual and clothing of its inmates.” Bingham soon passed to the Paganels (or Painells) who, with others, made various gifts to swell the priory’s interests here, where Thurgarton Priory and Welbeck Abbey also obtained possessions.

Esdaile’s “History of Bingham” (1851) records the discovery of the base of an octagonal tower in Castle Hill field, and this and the field name, suggest the existence of a fortress of some kind of which no annals are known. If there was a castle here it may have been erected by Roger de Busli (a great builder) or (perhaps more probably) by Ralph Paganel, the reputed betrayer of Nottingham Castle to the Earl of Gloucester in 1140, in which case it would be one of the hundreds of “castles” that sprang up during the turbulent reign of Stephen.

Under King John and Henry III the manor more than once changed owners, Fulc Paganel forfeited it by rebelling with the barons, and Henry Baliol, to whom it was then given, similarly lost it. In 1228 King Henry bestowed it upon Nicholas de Lettris, reserving the right to give him compensation elsewhere in the event of Paganel being pardoned and restored, but in 1235 Nicholas was displaced in favour of William de Ferrers, Earl of Derby, whose son sold the lordship to Ralph Bugge, a wealthy woolstapler of Nottingham, who soon acquired the advowson also. He was the founder of the family that took its name from its seat at Willoughby-on-the-Wolds, whence it removed to Wollaton and became ennobled as the Barons Middleton.

First Bingham.

His son Richard made his residence here, adopted Bingham as his surname, and was knighted by Edward I. The last of the line of these local lords was dead by 1388, for his grandson, then a child, seems never to have possessed the lordship. It was probably during their regime that the church (of which the tower remains) was erected, and about 1300 Sir Rd. de Bingham built for himself the Chapel of St. Helen and founded in it a chantry for masses to be celebrated there for his family past, present and future.

Many events of local interest occurred during the sway of the Binghams, One of its parsons turned publican and was so notoriously an evil liver that he escaped deprivation and worse by a heavy fine and promise of reform, and his immediate successor was actually ejected from the living for gross misconduct; and in 1287 fled to escape condign punishment. In 1276 the Knights Templars and Hospitallers were accused of extortion, and a few years later the rector, charged by Blyth Priory with seizing the tithe sheaves of corn growing on its land, agreed to retain the tithe, paying four marks a year for that right. In 1291 Grey Friars were ordered to preach here in aid of the Crusade; in 1299 the market-place was one of the six places in which the lady of the manor of Staunton was to be whipped, her sentence perhaps being the more severe because her paramour had made the ecclesiastical messenger eat the summons he had brought.

An annual fair of six days and a weekly market were established, and in 1311 a grocer of East Bridgford was committed to the Assizes for stealing cloth at the fair. Disputes and outrages were rife, outlawries were recurrent, and in 1347 Rd. Moryn of Car Colston and others were said to have driven away the horses of William Deyncourt and Ralph de Sprotburgh, stolen their goods and so intimidated their servants that they fled into long hiding. The choking-up of the streams constantly caused floods and commissions had to be appointed from time to time to enforce the “scouring” of the brooks and ditches and the repair of highway bridges that had broken down. In 1387 Sir Rd. Bingham had letters of protection for his properties whilst he was on the king’s service at sea, but when it was found that he had retired into Cheshire the protection was withdrawn. Finally, in 1390, an inquisition was held as to the possessions “held by Sir Rd. Bingham at the time of his outlawry” and as the manor was held from the king it was seized into the king’s hands and the interests of the Binghams in Bingham ceased, but the family retained properties at Car Colston and elsewhere.

Rempstone Ownership.

The next owner of the manor was Sir Thomas de Rempstone, one of the county’s great worthies, who figured in Shakespeare’s “Henry IV” as Sir John Ramston. He landed with the future Henry IV at Ravenspur in 1399, helped to depose Richard II, whom, as constable of the Tower, he guarded as prisoner, was admiral of the fleet that guarded the southern and western coasts, and was drowned in the Thames when trying to shoot the rapids at London Bridge. His body rests beneath a floor-slab in the chancel of Bingham Church. His almost equally famous son took 32 retainers with him to share in the glories of Harfleur and Agincourt, but in 1426 when fighting under the Duke of Bedford he was captured by Joan of Arc and heavily ransomed. He died in 1458 and was buried beside his father, his estates passing with the marriage of his daughter to Sir Brian Stapleton from whose descendant in the time of Elizabeth Bingham was purchased by Sir Thomas Stanhope, grandfather of the first Earl of Chesterfield.

Sir Edw. Stanhope was one of the leaders of the royal army which closed the Wars of the Roses and securely placed the first Tudor monarch on the throne by the decisive victory at Stoke in 1487. It may be regarded as certain that Bingham men fought there, for as Henry VII marched through Notts, he commanded the people to arm themselves and join his ranks. Passing through Radcliffe with his army on his way from Nottingham the king spent the eve of the battle here, and it is said that at dawn he and his host were led by a local guide by devious ways from Bingham to the “most bloody battlefield on English soil.”

Account Of Bingham's Development and Decline

IN addition to the already-mentioned Chapel of St. Helen two others are sometimes said to have existed in mediaeval Bingham. One is assumed from the name of Chapel Yard where human remains have been found; the other is supposed to have stood in Crow Close, on the evidence of some foundations, but both claims are doubtful. Mr. Godfrey confessed himself “unable to find references to other religious institutions in Bingham than the domestic Chapelry of St. Helen and the Guild of St. Mary,” which had a guild house in the township and apparently an altar in the south transept of the church.

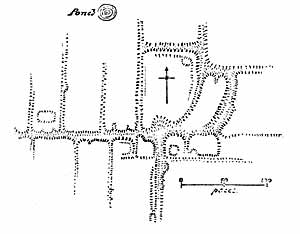

Earthworks in Crow Close, Bingham, by Arthur Hadrian Allcroft (1908).

Earthworks in Crow Close, Bingham, by Arthur Hadrian Allcroft (1908).Thoroton makes passing reference to a Chapel of St. James, which had vanished before his time, but the Chantry Commissioners, who in 1546 noted St. Helen’s, made no reference to any other chapel here, which shows that if such were in being they were devoid of any chantry. The remains discovered in Chapel Yard may perhaps be associated with victims of the frequent plagues, while Mr. Allcroft’s sketch-plan of the foundations in Crow Close indicates something much larger than the site of a chapel. At the Reformation when the monastic, chantry, and guild properties were sold to speculators (who soon made their profit of them) no grants of chapels other than St. Helen occur, and documentary and physical evidence of the existence of such structures are alike wanting.

Famous Fair.

By the 17th century Bingham Fair was renowned enough for its “hogges” to attract purchasers from afar, and Belvoir Castle was not the only house that in October filled its byres with pigs from this source to provide hams and bacon for the coming winter. In 1604 the plague was so virulent in certain neighbouring villages that the inhabitants were debarred from attending either the market or the fair, and in 1636 this parish was itself similarly stricken. Situated in the Vale of Belvoir, between the Parliamentary stronghold of Nottingham and that of the Cavaliers at Newark, skirted by the Fosseway, and the meeting- place of cross-roads, Bingham was the scene of historic events during the Civil War. In 1643 a body of 700 Roundhead troops beaten off from Wiverton Hall took refuge here; in March, 1644, Prince Rupert, making his surprise march for the relief of Newark, bivouacked in Bingham fields ere setting off by moonlight to circumvent the foe and brilliantly succour the “Key of the North,” and a week later he rested here again on his return journey.

At one time or another troops of both sides were here and, indeed, the township was rarely free of them and their perpetual distraints, and when the fighting was over there was an unhappy aftermath. The terms of the capitulation of Newark in 1646 allowed the contestants to quit the town with all the honours of war, but they bore with them germs of the plague and Bingham was quickly ravaged by it. The Stanhopes were Royalists, and as such the victors seized their estates. In 1650 the widow of Lord Stanhope petitioned for the restoration of the rents of her jointure in the manors of Bingham and Whatton, and it was found that “during the wars she abated her tenants of two-thirds of their rent . . . and that many arrears are due.” Her petition was probably granted, and ultimately Bingham returned to the Stanhopes as Earls of Chesterfield. The Earl (afterwards Duke) of Newcastle had property here which was seized and sold, and smaller “malignants” had to lose their little properties or compound for them as best they could.

Religious Troubles.

Under Charles II the local annals largely relate to religious troubles. The fact that the Rev. Samuel Brunsell became rector in 1662, when so many Puritan clergy were ejected, suggests that some “Godly preacher,” probably Presbyterian, then quitted the living. Reynolds, ejected from St. Mary’s, Nottingham, found a refuge here in 1666, and Wm. Cross, who had been Presbyterian vicar of Beeston and Attenborough ministered from 1669 to 1672 when he was licensed to preach at the house of Mr. Porter, but in 1673 the licence—like all others of its kind—was withdrawn. Two of the inhabitants, named Chamberlain, were informers against Quakers, but in 1676 the curate reported that the 326 adult inhabitants included no Papists and only ten who refused to take the Sacrament. Sixty-six years later there was one family of Quakers “and an inmate of the Church of Rome.”

The tide of charity that set in generally towards the close of the 17th century reached Bingham. The widow of Rector Brunsill (who ceremonially laid a ghost in the village) left £5 for the poor, as also did Thomas Porter during the Restoration era, and more substantial benefactions followed. In 1694 Sir William Stanhope founded an almshouse at Shelford for the poor of Bingham and other parishes, and William Tealby, who died in 1722, bequeathed £100, of which the interest on £50 was to be distributed in bread on Christmas Eve, the other moiety to be spent upon teaching poor children. The money was invested in property at Car Colston, and if the proceeds are not still administered, exactly in accordance with the wishes of the testators, they were a few years ago. The teaching charity was not the first of its kind here, for as early as 1533 the rector, John Stapilton, had established a free school or such repute that Cranmer suggested his nephews should be educated there. In 1764 George Bradshaw, and in 1779 his widow, each left £50, invested in the newly-established Bingham turnpike, the interest to be given to the poor on New Year’s Day and Good Friday respectively. Other charities followed, including £80 as the proceeds of a series of theatrical performances given by public-spirited local amateurs in 1784-5. Lands were purchased, and a century ago the Charity Commissioners reported that the funds were being properly distributed. They now produce about £40 a year.

Defoe's Visit.

Defoe passed through Notts, in 1723, but all he could find to say of Bingham was that it “is a small market town noted for a parsonage of great value.” He might have added that in a two-roomed tenement built for the purpose in the centre of the market-place was still confined a chained maniac who had tried to burn down the township in 1711, as he continued to be until death released him in 1739, and that in 1711 worshippers in the church had been scandalised by a drunken visiting parson collapsing in slumber in the act of reciting “O Lord, let me never be confounded.” He was pelted out of the village. Sixteen resident and three non-resident owners then represented the local voting strength, and it is claimed (somewhat doubtfully) that soon after this date Stafford’s printing works were founded. John Wesley, who preached here in 1770, came jaded from Nottingham, and was unfavourably impressed. Two unsympathetic clergymen were among his hearers and most of his congregation “gaped and stared” as if they had “never heard of death and judgment before”; but Methodism had come to stay. Five years later the church spire was struck by lightning and eleven boys who had sought shelter in the porch were injured.

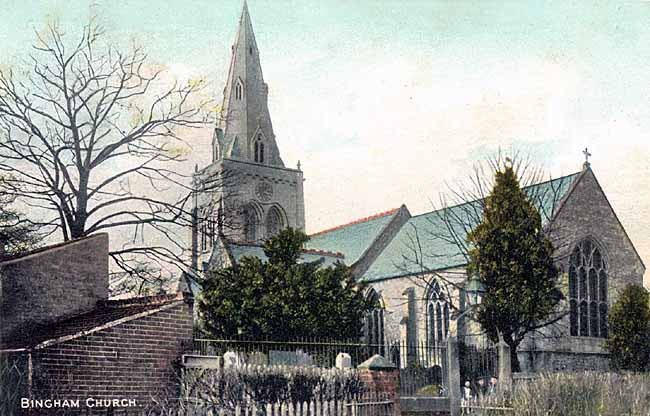

Bingham parish church, c.1905.

Bingham parish church, c.1905.The fine cruciform church, —which celebrated its seventh centenary in 1925, is full of interest of which there is little space here to tell. Its 13th century tower and rather later spire are beautiful exterior features, and, despite ravaging “restorations,” the interior offers much of historic charm. In the south porch stands a Norman font. The arcades, with noteworthy sculpturing, date from about 1300, to which period the piscina, sedilias and some windows also relate. The base of the roodscreen and the east window are nearly 500 years old; the cross-legged effigy in the chantry chapel is believed to represent Sir. Rd. de Bingham, c., 1300, and there are other ancient memorials more or less defaced. A water-colour sketch in the vestry shows how the interior looked before the nave was heightened by a clerestory in 1874, or the chancel was restored in 1845. The chantry chapel was rebuilt in 1874, and Dr. Felix Oswald has suggested the possibility that stone from the walls of Roman Margidunum are embedded in the fabric of the church.

Reformist Rector.

Towards the close of the 18th century the Parliamentary enclosure of the commonable lands took place, though it is thought probable that a smaller private enclosure had been made about the time of Anne. In 1790 a post-office was established, and the construction of a branch of the Grantham Canal marked further progress. The new century found Bingham a busy little market town with five fairs—for cattle and hogs—during the year, a weekly market, that was the central mart for the district produce. It was alive with mail-gigs, stagecoaches and carriers’ wagons, though the Fosseway and the turnpike which by-passed the market-place diverted much of the traffic. In 1818 the rector (Robt. Lowe) achieved fame for himself and the parish by instituting reforms in the grossly abused system of outdoor relief of the poor, which immediately increased wages and reduced crime and expenditure and was widely copied.

In 1850 the population had increased to its maximum of 2,054, but in that year the Great Northern Railway opened its station here, and a steady and persistent decline set in, with the result that forty years later the modern minimum of 1,487 was recorded. With Nottingham, Grantham, and Newark brought within easy reach Bingham’s importance declined and has never been recovered. In 1871 the death of the 7th Earl of Chesterfield without issue left his sister his sole heiress, and she carried his estates, including Bingham, by marriage to the Earl of Carnarvon. The empty market-place gives a misleading air of decay: Bingham is not in fact the “Sleepy Hollow” which a casual glance might suggest, and the place that witnessed the birth of Viscount Sherbrooke in 1811, and the death of James Prior Kirk, the novelist, in 1922. has claims to national remembrance.

< Previous