Besthorpe

By JOHN GRANBY.

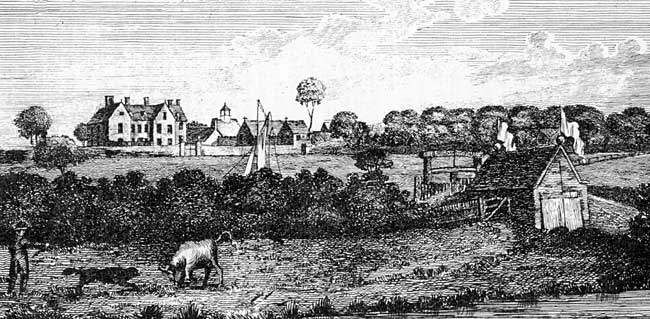

Beesthorpe Hall, "The Seat of Samuel Bristowe, Esq." in 1796.

Nottinghamshire has two Besthorpes, one a hamlet of Caunton, the other some half-dozen miles distant "as the crow flies," between Collingham and Girton. It is with the former that this sketch is concerned, but as both villages frequently masquerade in old records as "Bestorp, co. Nottingham," and collateral clues are often non-existent, it is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to distinguish between them. Dr. Thoroton had little to say of either of the Besthorpes, and other local historians have been apt to ignore one or both of them, while a possible means of differentiation by spelling the name as Beisthorpe or Beesthorpe has been defeated by the application of these forms to them both.

The Rufford Hunt at Beesthorpe Hall, c.1910.

The name itself is, another puzzle; there are plenty of conjectures as to its derivation but no one can definitely say whence it comes or what it means. The Place-Name Society suggests the Anglo-Saxon "beos," which it tells us means bent grass, as the most likely origin, but other authorities favour a personal name such as "Be," "Bes," "Besa," or "Besi" of whom nothing is known. The name of a stream (also unknown) has been put forward, and local folklore has it that the prevalence of beehives, or clearings, in the woods where beasts grazed, supplies the answer, but the only thing certain is that the suffix "thorpe" indicates Danish occupation. The original settlement was doubtless an offshoot from Saxon Caunton, and it was probably a small colony which the Danes, developed, its tardy beginning being due to the environing woods of which 90 acres yet remain.

Time of Conquest.

At the time of the Conquest Tochi, the Saxon lord of Laxton, had land here in socage, as also had the royal manors of Mansfield and Grimston. Some of the soil was held by the Conqueror in demesne, but Tochi's portion appears to have gone with Caunton and Laxton to the Norman Geoffrey de Alselin, who held of the king in chief (as his responsible tenant) in return for the performance of feudal duties. By the middle of the 13th century "the hamlet of Besthorpe with the soke of Grimmeston" had the Lacys, Earls of Lincoln, for its overloads, from whom Jordan Folyot, lord of Jordan's Castle at Wellow (who died in 1299) held it, but smaller holders had established themselves, and some had bestowed various pieces of land upon Rufford Abbey. Thus, early in the reign of Henry III (1216-72), Hugh, son of Richard de Caunton, gave it a small parcel of land of his own and confirmed a slightly larger grant by his father; Thomas de Muskham waived in the abbey's favour his right to 6s. of yearly rent; in 1250 William de Besthorp gave the third part of his property here, and in 1287, at the inquisition post-mortem of Robert de Everingham, the great lord of Laxton, had given to the monks half a knight's fee in Kirketon, Walesby, Willoughby, and Besthorpe, worth £10 yearly, all of which the Abbey got the king to confirm to them. It also secured confirmation of the privileges it had obtained for itself and its tenants, including exemption from secular exactions on all that was bought or sold by them or was conveyed for or by them by land or water, and the right of free warren for the monks throughout their lordships.

A Medieval Life Assurance.

The third part of his land here which Win. de Besthorpe gave to Rufford had been assigned as the dower of his wife, and in making the gift he stipulated that the monastery should provide her with board and lodging for the term of her life. Every day it was to provide her with a loaf of the superior bread such as was supplied to the monks, with one loaf of the kind of bread given to children and another of household bread fit for servants. She was to have yearly three quarters of oats and one of barley, delivered at stated intervals, the latter being doubtless for her brewhouse. This was what was called a corrody, but in this instance it did not entail residence in the abbey buildings, as it sometimes did, for the monks domiciled her in a toft or homestead which they had acquired in the village by gift from Stephen de Besthorpe, and allowed her the use of another toft, perhaps for her servants. It was a common and pious form of medieval life assurance of the endowment policy kind, and after her death the property remained to the monks without encumbrance.

In 1327, Edward III, then a minor in the tutelage of his mother, Queen Isabella, and the notorious Mortimer, issued a "compulsory persuasive" for financial aid for the war. In response, Henry de Venellis (Henry in the Lane) appears to have gathered in the local offerings and remitted 13s. 6d. from "Besthorpe and its soke." Six years later there was an appeal for money for the Scottish war, to which Robt. de Besthorpe contributed 3s. In honour of the knighting of the king's son in 1346, Rufford paid £4 in respect of its two knights' fees at Cratele, Lound, and Besthorpe, and Nicholas de Barnak sent 20s. for the half of a knight's fee he held here.

A Timely Warranty.

A few years before the outbreak of the - Wars of the Roses the manor passed to Richard Bingham—probably the great landowner who, in 1447, became a Justice of the King's Bench, and the deed of its conveyance contained a warranty against any claim that might be made for it by the abbots of Westminster at any time. There is no evidence that any such claim was ever made; perhaps the warranty checked existing aspirations in that direction.

When the great rebellion of the Pilgrimage of Grace broke out in 1536, no one played a more effective part. in its suppression than George. Earl of Shrewsbury. This formidable rising, which for a time threatened, to topple Henry VIII from his throne, was due chiefly to the royal breach with Rome, but there was a widespread belief, in which the inhabitants of Bestorpe may have shared, that a fine was to be paid for every wedding, funeral or christening; that a tax was to be levied on every head of cattle or the cattle would be forfeited, and that "no man should eat in his house white meat, pig, geese, nor capons, but that he should pay certain dues to the King's Grace." There was much smothered sympathy in Notts, with the rebels; Sir John Markharn warned tenants of monastic properties to keep aloof ; the vicar of Newark was executed for participation in the rebellion, and Lord Hussey (who shared a like fate) forfeited his estate at Kneesall by his attaint. Lord Shrewsbury assembled a loyal army at Nottingham, and it was his activity which undid the rebels. His well-earned reward was a liberal grant of possessions of suppressed religious houses, including Rufford with all its properties here and elsewhere. The Cistercians were great farmers, especially of wool, and their lands at Besthorpe would be well cultivated, the pastures being studded with sheep.

Lost Chapel.

Here was formerly a chapel-of-ease, of which no traces remain, and the will of Richard Greve, dated 1535, suggests then it was then too decayed for use as, although he made bequests to the churches of Caunton, Maplebeck, Kneesall, and elsewhere, he left nothing to the old chapel that stood beside the manor house until the beginning of the 18th century, when a Bristowe destroyed what was then standing of it to enlarge his bowling green.

The village had normally a quiet existence, but a few scattered details of minor troubles during the reign of James I have come down to us. In 1616 the overseers, in pursuance of the then new Poor Law Act, were ordered by the magistrates to provide a dwelling for a poor woman who had been evicted by Francis Bristowe from a tenement he owned. In the same year a husbandman was "presented at court" for damaging the village bridge, and in 1618 a reluctant Thos. Bristowe was compelled to fill the office of parish constable, he being "next on the list of those nearest thereto."

Colliery Intrusion.

Among the properties purchased by the Bristowes (who ultimately became possessed of the whole lordship) was Rufford's old monastic grange, which became a dwelling, but in the time of "James the Sixth and First" that family erected a spacious mansion with gables, towers, a central hall, and "very extensive offices," to which the family removed from Elston. Throsby (vol. iii, p. 143) gives a view of it as it appeared in 1796, and states that the village once had a charity school, which has vanished and left no traces. There are yet to be seen remains of the moat that surrounded the old Hall, that was unoccupied a century ago, and shortly afterwards was pulled down. In 1795 the Enclosure Act was passed, with the result that 803 acres of open land were enclosed, the award giving details being now in the custody of the clerk to the local council.

Beesthorpe Hall in 2007. The earliest parts of the house date from the 17th century. It was remodelled and stuccoed 1770-71. The wings were added in the early 19th century.

It was this Besthorpe which, about 100 years ago had its amenities threatened by the intrusion of a colliery. Dean Hole narrated that it was then confidently asserted that beneath its soil was a rich substratum of coal, and Mr. Bristowe was induced by a plausible adventurer to expend a considerable sum in search of it. Many workmen were employed without satisfactory results, and when Mr. Bristowe announced that he would abandon the attempt, the clerk-of-the-works, unwilling to lose his lucrative post, proudly diplayed some small fragments of coal that he declared had just been dug up. Mr. Bristowe scrutinised the sample, and, having discovered unmistakable crumbs of bread and cheese mixed with it, he cynically informed them that "they had made him the richest man in England, for they had not only discovered a mine of coal, but also one of bread and cheese." The clerk-of-the-works had inadvertently blended with the coal some crumbs from his lunch, and the secret was out. Two hours later "there was not a man to be seen on the works."