The Reformation.

A few years later, however, as one result of the Reformation, the Bishop surrendered to the Crown all his rights here, but before doing so he granted to Forster "for his faithful service and counsel rendered and to be rendered," a lease of "the manor of Balderton, with the lands, meadows, feedings, and pastures belonging to its demesne," for £4 a year. To John Pickering went the parsonage (but not the right of presentation to the living), with its appurtenances, but from this lease were exempted "all manner of trees" and the right, to dig for "stone or chalke playster and earthe for the makeyng of brycke." The prebendary of Farndon and Balderton was to undertake at his own cost the "great reparations"—the "principal timber, stone, tiling, and leading of the church, houses, barns and other buildings of the prebend," and Pickering was to rebuild within two years any prebendal premises that might be destroyed by fire through default of the tenant, and to do all minor repairs. He was to underpin "wallys, studdyng, wyndvng, eight foote high, also the thatchyngs, ditchyngs, and hedgyng" at his own charges and was forbidden to cut down the woods.

It is possible to delineate much of the appearance and daily life of Balderton at that time, 400 years ago. Its overlord until 1547 was the Bishop of Lincoln under whom the Bussys held the manor, the prebendary also having properties and rights. Its venerable church was being shorn of some of its old ritual; there was a manor-house, a grange, parsonage, half-timbered thatched cottages with mud walls and plaster floors, a village cross and, perhaps, the present dovecote which is of Tudor date. The rearing of sheep for wool was declining, but the culture of grapes for wine continued, and in addition to farming the local industries were making ropes and bricks, quarrying, and the growing of flax, which had recently been made compulsory in every parish. Old feudal customs were dying harder here than in some other places, for the Bishops of Lincoln had obtained the right of holding courts and of sentencing offenders to the gallows or tumbril or taking fines tenantry. These had doutbless lapsed so far as criminal punishments were affected, but Anthony Forster was complaining that the sheriff was interfering with the rights he had obtained to exact view of frankpledge (by which neighbours were made responsible for each other), to assize of bread and ale, seizure of the goods and chattels of condemned felons and fugitives from the manor, and waifs and strays—all of which he claimed to himself. The "old order" was passing and with the accession of Elizabeth in 1559 a new era was to dawn.

A YEAR after the accession of Elizabeth, Balderton Church was falling into ruin through lack of repairs, and there was no resident parson. Soon afterwards a John Beswicke was found to be serving the cure without authority. It was difficult at that time to find suitable Protestant clergy, and Beswicke appears to have stopped the local gap by intruding himself. At the Archdeacon's Court he admitted the charge and prayed to be officially admitted, but was probably ousted, Church troubles continued, and 25 years later the vicar was accused of failure to administer the Sacrament, when he defended himself by claiming that he was not compelled by law to administer at the times complained of, and that bread and wine were not provided for such use.

In 1559, also, the lease of the Grange and possession of other properties descended to Robt. Markham and thence to his son, another Robert, a courtier, whom the Queen dubbed "Markham the Lion," but whose extravagance caused Thoroton to describe him as "a valiant consumer of his estate." He exchanged his lands here with Anthony Staunton, and had so completely wrecked his fortune that at his death his inheritance had to be sold to liquidate his debts. It was during this reign that the Bussy heiress carried the manor by marriage to the Meeres, and a series of new owners commenced.

Agriculture.

Apart from such events, the annals of Elizabethan Balderton relate chiefly to agriculture. In 1566 one farmer was fined and had to do double penance in church for cutting barley on a Sunday and making exceedingly uncomplimentary remarks about the Archbishop of York, while another "was detected repairing "Swenton's bridge" on the "Saboth daye," and churchwarden Spawton had to pay 20s. for trying to hush up the offence. The parish lands were unenclosed; transgressors who destroyed landmarks, ploughed beyond their limits, or in other ways broke the field laws were constantly under correction. In those days, as in these, the country was long in imminent peril of invasion, and the musters were often being drilled, the village arms and armour had to be kept ever ready for service; a sharp look-out was maintained for

warning beacon-fires, and when the Spanish Armada threatened and public-spirited Notts men were contributing money for the defence of the realm, Christopher Newcombe, of Balderton, was among those who subscribed £25. In 1599 the law courts upheld the feudal custom which compelled farmers of this parish to send their corn for grinding to Newark mills, but the decision did not pass unchallenged, and the practice gradually ceased.

Plague.

The Stuart era was ushered in by a plague of such virulence that collections were made in other churches for the relief of the inhabitants here, and by the creation of overseers, under the first Poor Law (1601), which threw upon them the onus of preventing poor strangers from settling in the parish, setting the poor to work, and punishing vagrants. Fines were imposed upon occupiers who failed to take their turn at scouring the ditch between Balderton and Newark or shirked their obligation to mend the local roads. A recent law forbade the erection of dwellings with less than 4 acres of land, but in 1610 the Justices condoned some unlicensed cottages on the ground that they we're built for "diggers of stone in the quarries."

When the Civil War broke out in 1642, Balderton found itself in parlous plight with Newark cavaliers making forays while the town was besieged and Parliamentary troops all around. Early in 1644, Sir John Meldrum. commander of the latter, hearing that Prince Rupert was approaching for the relief of Newark, took possession of the Dowager Countess of Exeter's mansion, here, but Rupert deftly side-tracked this stronghold and marched through Coddington at dawn.

So cheerily at midnight blew Prince Rupert's bugle horn.

And old Newark rose before them, as rose the early morn.

They are seen upon the hill-top, all dark against the sky;

They are sweeping down the hill-side to death or victory;

They have burst upon the rebels, and Newark heard the hymn—

None ever sounded sweeter—" For God and for the King."

As a detachment of Parliamentary Horse was advancing to its Balderton quarters after a melee in which the Cavaliers had the best of it, they were intercepted by a body of Royalists, who, taking them by surprise, put them to flight, took their colours, and carried 200 prisoners off to Newark.

Final siege of Newark.

In December, 1645, when the final siege of Newark began, this village was occupied by Col. Rossiter with a force from Grantham; a fort was erected, and it must have been a relief to the inhabitants when Charles surrendered in May. The Parliamentary Commissioners made their headquarters here, for Newark was plague-ridden and still held out despite royal orders to capitulate, and here they awaited the delivery of the king's disguised companion, Dr. Ashburnham, who had been specially exempted from all terms of mercy. From London, the Deputy Sergeant-at-Arms came to take charge of the captive, but while the English and Scots were haggling about King Charles, the captive made good his escape. When Newark at last reluctantly obeyed the King's behest and capitulated, the plague quickly spread here with devastating effect, and in 1646 there were 129 burials in its churchyard compared with 19 in the previous year. The distress continued long, and as late as 1691 the county justices ordered inhabitants of neighbouring villages each to contribute 6d. a week towards the relief of the poor of this parish.

As a reward for its sufferings during the war the "Merry Monarch" placed Balderton, Coddington and Winthorpe under its governance, and conferred other privileges upon that faithful town; he also granted the manor of Newark with its appurtenances here to his neglected queen. In 1676 the vicar reported that his 256 adult parishioners included no Dissenters of any kind, but he must have turned a blind eye upon Thomas Baggot who four years later was fined for "keeping a conventicle in his own house." Sixty-seven years later the parish had 60 families and there was a solitary Quaker.

Interesting church.

St Giles church, Balderton, c.1910.

The church in which those people worshipped still stands, looking much as it then was save that its clerestory has gone. It offers much of interest inside and out. Its two Norman porches are among the finest in the shire and are of Late Norman work. That on the north side was rebuilt 700 years ago and is notable for its ornamentation and its two doors. The outer one was originally at the inner end. Both are fine specimens of early woodwork, and the church is one of the few which can yet show ancient images in niches over the doorway. The chancel is Early English, as is the arcading on the north side and probably the north aisle, but the deep three-light window in the south wall was an insertion of the 15th century to improve the lighting. The lower portion of the tower was commenced in the early part of the 14th century, and its base suggests that a taller structure was designed; its completion may have been stayed by the Black Death (1349), and when its erection was resumed a century later, the tower was left low and provided with its spire. The beautiful carved oak screen dates from about 1475, and if (as is alleged) the pulpit is of the same period it must rank with that at Wysall as the only two pre-Reformation pulpits in Notts. Space forbids recital of other notable features, but passing mention must be made of the 42 old benches of 15th century workmanship, whose "poppy-heads" have carvings of couples of hares or rabbits hung head downward.

Benefactions.

In 1609 Agnes Newcome left 6s. yearly for poor widows of the parish and under the first two Georges came a spate of benefactions. In 1724 Gabriel Alvey bequeathed 40s. a year to be given in bread at the church door on the Sunday following each quarter-day, and he also gave improving property, then yielding £8 per annum, for the education of poor children. From Benjamin Gibson came in 1727 a house and homestead for a Sunday school, and in 1812, aided by subscriptions, a school-house was erected and a flourishing school ensued. The Wigglesworth charity provided twelve small loaves for poor households every Sunday and a recurrent distribution of coals. Other charities are recorded on a tablet in the church.

Modern developments.

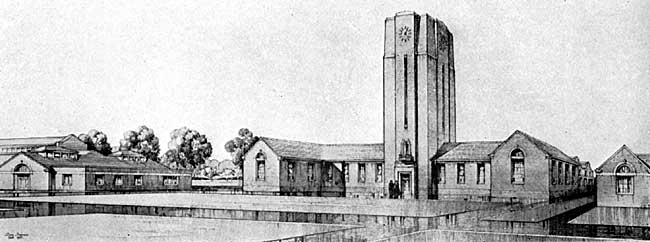

Balderton mental hospital.

In consequence of frequent disputes respecting the open fields a scheme was mooted in 1692 for enclosing them, but it proved abortive, and it was not until 1768 that the enclosure was actually made. Soon after that date the oats grown here were of so superior a quality that experts could distinguish them from all otter growths. At the close of. the 18th century, the parish comprised a hundred dwellings. In 1836 the manor of. Newark with its valuable possessions here were sold by the Crown to the Duke of Newcastle, and three years later the village suffered severely from the great storm, most of the church windows being blown in. In 1840 was built the "New Hall," which, exactly a century later, the County Council was enlarging and converting into a mental hospital at a cost of £250,000. The Newark isolation hospital had been erected in 1906, and Balderton, is now a populous village, suburban to Newark, with a population of about 2,900, of whom some 500 are employed at engineering works famed for the manufacture of ballbearings, and in New Balderton it has a berewick-like offshoot of its own.