< Previous

NOTTS. VILLAGES

Attenborough: an ecclesiastical parish only

By JOHN GRANBY

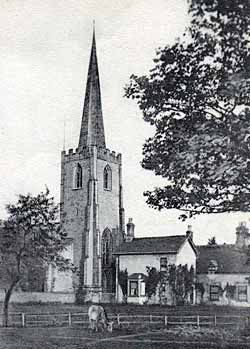

Attenborough church and Ireton's house, c.1910.

Attenborough church and Ireton's house, c.1910.Attenborough is something of a curiosity, for although it is an ecclesiastical parish as a civil parish it has no existence. Its church, churchyard, and the so-called “Manor House” are in the administrative bounds of Toton and its other lands are in Chilwell. How it has befallen that so fine a church is to be found in such a small and isolated village is not known with certainty, but it is supposed, that it was once larger and more important than Chilwell or Toton, and that the Trent in one of its meanderings changed its course and swamped the ancient settlement.

The village name derives from a person named Adda, probably of early Saxon times, but its history goes back to the Roman era, when there was a burh or fort that guarded the passage of the Trent. The settlement became known as Adda’s-burh, and it was not until the 17th century that the double “d” gave way to the double "t" and the spelling assumed its modern form.

Relics of ancient ford

When the Trent runs low in times of drought, vestiges of wooden piles disclose the ancient ford which linked Attenborough with Barton. There was a British camp at Brent’s Hill and a Roman villa (and probably more) at Barton. On the south side of the river a road came up from Leicester via Stanford, whilst on the northern bank a Roman road, now known as Coventry-lane, struck off to the north, skirting Sherwood Forest, and an easterly branch, represented in part to-day by Hassock-lane, led through Lenton to Nottingham. Relics of Roman occupation have been turned up here from time to time, but the earthworks have gone—maybe washed away or buried under the bed of the river.

Nothing is known of the Saxon history of Attenborough, and as it is not specifically mentioned in Domesday it may be assumed that by the time of the Conquest it had dwindled to inferiority in comparison with Chilwell and Toton, each of which had “half a church,” the two halves being moieties of the church here, of which scanty fragments remain. One of the moieties belonged to the fee of a Norman knight, Ralph Fitz-Hubert whose tenant, Odo de Boney, bestowed it, with the consent of his overlord, upon the priory of Lenton shortly after its foundation. The other half was of the fee of Peverel, and passed to the Greys of Codnor, whose forty- year lawsuit with that priory respecting the living was terminated by the arbitration of the Archbishop of York in 1240. To “avoid the effusion of blood” he ordered that 40s. be paid to Lenton yearly “in the name of a simple benefice of that moiety to which the chapel of Bramcote was attached, and that the other part should remain with the Greys, the prior to pay 1lb. of frankincense yearly at Attenborough Feast.” The Greys granted their share to Felley Priory in 1337, and within a few years the rectory was consolidated by an annual payment. When Felley was dissolved, in 1538, it was still receiving 106s. 8d. as a pension from its foregone tithes from this parish.

Missing cross

In an unpublished portion of his “Hundred of Broxtowe,” Major A. E. Lawson Lowe records “a local tradition that a market was held at Attenborough in ancient times, arid the stump of an old cross, standing at a short distance to the north-west of the church, in ‘Lady Cross Field,’ is pointed out as having been the market cross.” The base remains but the shaft has gone, and forty years ago Mr. Stapleton saw at Chilwell the shaft of a mediaeval cross serving as a gatepost, which he suggested might have been taken there from the Lady Cross Field. This cross was known as St. Mary’s— which seems to imply connection with the church—and it is said that around it formerly clustered numerous dwellings, of which all traces have long disappeared.

St Mary's church, Attenborough, in 2004.

St Mary's church, Attenborough, in 2004.The church, dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, offers much of interest including examples of many of the architectural orders. It has a (rebuilt) Norman doorway; its lofty arcading is Transitional, of the last quarter of the 12th century; two of its notable slabs are Early English, and to the Decorated period pertain most of the tower, the chancel arch, south doorway and font. The beautiful spire has been ascribed by Mr. Harry Gill to the period just before the terrible Black Death of 1349. and that authority further states that it was the work of the skilled band of York masons who produced much fine work in this county and were responsible for the chancel at Barton and the spire of St. Peter’s in Nottingham but others date it a century later. Two square-headed windows on the south side of the chancel are of the time of Richard II and are of a pattern almost exclusive to Notts. There are three two-light Tudor windows, some nieces of ancient glass in the central light of the south side of the chancel, and other windows are “richly dight” with modern coloured glass.

A striking feature

The westernmost bays of the arcade have been cut in half by the intrusion of the tower, and the carving on the piers of the arcading is noteworthy on account of its curious figures, but the striking feature is the flying buttresses which pierce the building to support the arcade when the widened aisle developed an ominous bulge. There are two tall carved bench-ends of the 14th century near the priest’s door, on the north side, the altar-table is Elizabethan, and four Jacobean panels are preserved in the choir-stalls. The porch has the rare feature of an outer door, made of solid oak planking held together and hung by large and spreading strap-hinges. Mr. Gill says it may be “one of the oldest church doors in the county, dating back to the reign of Henry II [1154-89],” and that there are porch doors similar in age and style at Selston and Laneham. He adds that as this is obviously an intruder in its present position, it may have been removed from the built-up Norman doorway and fixed here for preservation when the porch was rebuilt in 1860.

In 1840 the church was re-pewed and a gallery added, and the whole building was restored in 1857. It was probably then that the rood-stairs were blocked up and the decrepit old pulpit displaced. For centuries the tower had five musical bells, of which two were undated and the others marked 1631, 1733. and 1749, but when these were partly recast in 1894 it was discovered that the tenor was a pre- Reformation bell of the late 13th or early 14th century. A sixth bell has lately been presented by Lieut.-Col. Pearson, of Bramcote, in memory of members of his family, of whom two sons perished during the war of 1914-18. The parish has more recently still been fortunate in another respect, for in 1937 Mr. Nevil Truman presented to the vicar and churchwardens the lost churchwardens’ account-book, which he had recovered and caused to be cleaned and repaired.

Inescapable lawsuits

The annals of a place which Thoroton described as “rather to be called a church than a village” are inevitably sparse. Until 1343, when Felley Priory acquired the advowson, the church was served by rectors, but thereafter by vicars, of whom some at least would be monks from that priory. In 1301 Thomas de Blockley, then rector, had a dispute with his parishioners of Bramcote respecting the repair of the chancel of the chapel there, which was dependent upon Attenborough church—for this singular parish included not only Toton and Chilwell, but part of Bramcote also. Another record tells that in 1430 Sir Nicholas de Strelley beaueathed 100s. for the poor of Strelley, Chilwell, Attenborough, &c., debarring from its benefits any who played unlawful games or frequented taverns at unlawful hours by night, unless they swore to reform. Sir Nicholas had acquired property here from the Cokfelds in 1405, and was looking after the welfare of his tenants.

In 1466 licence was accorded for the Prior of Lenton and the rector of St. Peters, Nottingham, to marry John Delves, Esq., of Donington, to Elizabeth, daughter of William Babington, Esq., of Attenborough, in the private chapel of the manor house at Chilwell. This wedding was not without local significance, for the Babingtons and Delves, together with the Strelleys, appear to have divided most of Attenborough between them. In 1501 Sir John Babington died, and his estate here, as well as his manor at Chilwell, descended through the Delves to the Sheffields, Elena Delves bringing her inheritance to Sir Robt. Sheffield by marriage about 1504. When Sir Robert died, in 1531, his property in this village was valued at £39 3s. per annum, and it was complained that the Earl of Shrewsbury under some pretext or other was holding it back from the heir.

There were the inescapable lawsuits, which then abounded everywhere, and from 1533-38 Sir Nicholas Strelley was suing Sir John Markham, son-in-law of John Strelley, for detention of deeds. John Strelley had died in 1501 leaving four daughter co-heiresses, and in 1535, when a family division of his large estates was made, Thomas Poutrell, heir of Margaret, second of these heiresses, chose for his portion Chilwell manor and possessions, here valued at £10 a year, held of the Greys of Codnor. The Poutrell memorials are among the notable features of Attenborough church.

Attenborough, the birthplace of a great man

IN 1538 the little priory of Felley was suppressed and its lands and buildings at Attenborough were purchased by Wm. Bolles. Out of its income of £61 4s. 8d. no less than £18 came from this parish, and by an economical arrangement the ex-prior was sent to the vicarage here, which had formerly been served by canons of his house, the Crown thus pocketing his pension of £6 a year. Darley Abbey had possessed “lands and a fishery in the Trent at Chilwell, Bramcote, and Attenborough,” which went to the Sacheverells of Barton, and in 1553 Sir Jas. Foljambe, grantee of other monastic properties, obtained the rectorial tithes and advowson for payment of £18 a year.

These sweeping changes yielded a fine crop of lawsuits, writes John Granby. Bolles at once claimed the plate and ornaments of the church; Richard Whatley, who had purchased Welbeck Abbey, and had a fine eye for the main chance, sued Bolles, and Godfrey Foljambe, who gave part of the tithes to Chesterfield Grammar School —which still retains it—had to fight for his rights against Sir Francis Willoughby, the builder of Wollaton Hall. The echoes of this litigation had scarcely died down when the district was ravaged by plague, which carried off whole families of “the parish of Attenborough-cum-Bramcote,” as well as in Chilwell and Toton.

An eminent native

Under the date of 1632 the vicar, Gervase Dodson, recorded the settlement of a warm dispute with his flock “about the buying of bread and wine for the communion,” by the arbitration of Sir John Stanhope, lord of Toton. Sir John directed that every farm should pay 8d. a year, each cottage 5d., and communicants 2d. It required some persuasion from the knight to induce the vicar’s assent, but he ultimately agreed upon the understanding that the parishioners should “be ready in all courtesy to fetch his fuel, coals and wood, and other commodities, and to do for him all neighbourly kindnesses, which they did all fairly promise.” In 1631 the harassed parson had been charged with others with making a “riotous affray,” but the differences were now composed, and the scale of payments was continued into the 19th century.

Henry Ireton by Jacobus Houbraken, published by John & Paul Knapton, after Samuel Cooper line engraving, published 1742 (1741) NPG D19476

Henry Ireton by Jacobus Houbraken, published by John & Paul Knapton, after Samuel Cooper line engraving, published 1742 (1741) NPG D19476© National Portrait Gallery, London.

Attenborough is one of those villages which have become famous through being the birthplace of an eminent man. Stratford-on-Avon is the classic instance: Aslockton is notable because of Cranmer; here it was Henry Ireton whose baptism is duly recorded in the parish register on November 3rd, 1611—the year of the first publication of the Authorised Version of the Bible.

When the Rev. John Mather held the infant at the font he would perhaps regard it with but little favour, for only two years had passed since its mother had been cited to the ecclesiastical court for refusing to be “churched” according to the rites and ceremonies of the Church of England. He may have been aware of the religious leanings of its parents, but he could not foresee that the child was destined to become one of the most influential forces of the Puritan Revolution. It was his successor, Dodson, who lived to see the Civil War and the prominent part his parishioner took in the conduct of public affairs. Ireton was the drafter of the famous Declarations of the Army, and was known as its “best prayer-maker and preacher.” More than any other man he influenced Cromwell, whose daughter Bridget he married; he was perhaps the finest military commander the county has produced; as a regicide judge he signed the death-warrant of King Charles, and having taken a prominent part in battles on English soil, he died in 1651 after a brilliant campaign, at the siege of Limerick, holding the office of Lord Deputy of Ireland. In life he had declined honours and pensions, but in death these were accorded, provision being made for his family in Attenborough, while his body was accorded a State funeral in Westminster Abbey and a noble monument erected over his grave. Seven, years later the Lord Protector was laid beside him, but at the Restoration their bodies were exhumed, hung for a day on the common gallows at Tyburn and their heads were struck off and impaled upon staffs over Westminster Hall.

Birthplace still exists

There is a tradition that Cromwell visited his daughter and her husband at Attenborough, and that during his stay his horses were stabled in the church. The former statement may well be true, but the latter may be doubted, for the number of churches (including Southwell Minster) reputed to have been thus desecrated is equalled only by the improbable multitude of country-house beds in which Queen Elizabeth is said to have slumbered.

John Ireton, Henry’s brother, who was born at Attenborough in 1615, was of lesser note. He settled in London, where he made a fortune, identified himself with the Parliamentary party, became Lord Mayor in 1658, was knighted, and at the restoration found himself excluded from the amnesty, but, escaping the worst punishment, was banished to the Scilly Isles. He lived to see the Revolution in 1688, and died in the following year.

Ireton's birthplace.

Ireton's birthplace.The Ireton birthplace still exists on the west, side of the churchyard, and enjoys the courtesy-title of “Manor House,” though there never was a manor here. The house to which Henry Ireton took his bride, on the other side of the church, has gone, and its site is now marked only by a few mounds. Its last occupant was named Morgan, and the place where it stood is now known as Morgan’s Close. Until a few generations ago the Manor House preserved several relics of the great Puritan, but they came to an untimely end when a busy housewife destroyed them as useless lumber.

Peace in religious troubles

Throughout the religious troubles of the reign of Charles II, Attenborough enjoyed unusual peace. Under the Commonwealth it had “a godly preaching minister and well disposed to Parliament,” but in 1662 the Rev. Wm. Crosse, who was also vicar of Beeston, was ejected, and the ritual of the Established Church restored. In 1676 the curate reported that the parish had 224 adult persons, including several popish recusants, but there were no Quakers, although there were some parishioners who persistently defied the law by refraining from attending Sacrament. This population of 224 included Chilwell, Toton, and part of Bramcote, for at that time Thoroton was writing that the village itself had “but few houses and no fields.” Enclosures had, however, been, made, and 1,332 acres had been converted to pasture here and at Toton. Dairying on a large scale had begun, and in the 18th century much of its milk was being converted into cheese.

The oldest Attenborough charity appears to have been that left by the generous Henry Hanley, of Bramcote, who, in 1646, left. 20s. a year for the poor here and at Toton, but a century ago this village was deriving no benefit from it, for Toton was taking 15s. and the balance went to Chilwell. A few months after the abdication of James II. Thos. Charlton, Esq., of Chilwell, bequeathed 20s. yearly for the vicar to preach an annual sermon on November 5th, in memory of “the nation’s deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot.” At the close of this service bread worth 6s. was distributed at the church doors in accordance with the will of Thos. Hallam, who had taken pains to ensure its continuance by providing a rent-charge to that amount out of a close at Bramcote.

Derwent navigation

In the early part of the 18th century strenuous efforts were being made to render the Derwent navigable, and Nottingham, fearing that through traffic would injure its trade, stoutly opposed these efforts and induced Attenborough and other places to petition Parliament against it, arguing that the price of corn would fall and farmers would be unable to pay their rents. Successive Bills were thus defeated, but in 1719 these local efforts failed and an empowering Bill was passed.

According to a terrier of 1777, the church was then “kept in very good order, having five very fine Bells, a good clock and an elegant singing Gallery.” Its “Silver half-pint Wine flagon” weighed 8½ ozs., and there was also a large pewter flagon. The folio Bible and Prayer Books were in good condition, but the scarlet plush cushion and cloth of the pulpit, “fringed with silk, and mark’d E.C. and M.C., the Gifts of Mrs. Elizabeth and Mary Charlton, are very ancient and much decayed,” as they might well be, having been presented in 1720. Hedges of quick shut off the churchyard on its eastern side, Robt. Holbrook’s house, barn, and thick walls enclosed it on its north and west, and to the south it was bounded by a wall and the brook. The parson appointed the parish clerk, an office which was monopolised for two centuries by six generations of Days, one of whom has a stone with an unctuous epitaph in the “God’s acre.”

The village, shut in on three, sides by the Trent, the Erewash, and the railway, remains somewhat isolated and small, although for some decades suburban homes have been established in it, without, however, impairing its quiet charm, and the Trent hereabouts is an excellent fishery, as it was in the days of the monks.

< Previous