< Wollaton | Contents | Places >

Worksop Manor

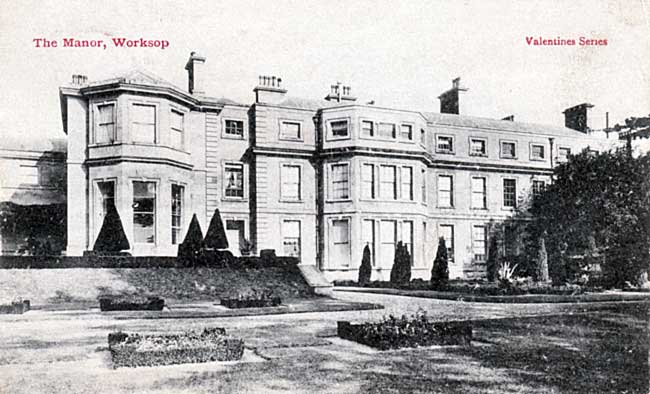

Worksop Manor, c.1910.

MR. William Isaac Cookson, who has occupied Worksop Manor since 1874, belongs to a family, whose estates lie in a county, which a popular novelist tells us, with painful iteration, has gloomy forests, bleak shores, and wild uplands. He is a Northumbrian, and his connection with this county commenced when he came to Worksop Manor. It has been my custom in this series of articles, from such particulars as I have been able to gather, to give some account of the county families, and the space that, from time to time, has been devoted to these accounts, represents the most difficult portion of my task in connection with these visits to the Great Houses of Notts., because the materials I have been able to gather in the course of a brief conversation, even in cases where these have been supplemented by information in black and white, have been necessarily somewhat imperfect. As Mr. Cookson does not represent a Nottinghamshire family, I am spared much of this trouble in noticing his interesting residence. It may not, however, be out of place to mention this much concerning him, that he is the third son of Mr. Isaac Cookson, J.P., who was once High Sheriff of Northumberland, that he is himself a magistrate for this county and for Northumberland, that he formerly resided at Benwell Tower, in the last-named county, and that he was born in 1812. Mr. Cookson has been twice married, and has a family large enough, with some twenty servants, to occupy the suites of rooms, which go to make up this very large house. One of his sons, who is in the army, and was engaged in the Zulu campaign, has contributed some very interesting things to the Manor House collection of curiosities. In the billiard room, where some of the books are kept, there is a cupboard full of articles from Zululand—assegais, charms, shields, and other instruments of warfare and emblems of peace. In another part of the house a large number of weapons, more easy to name than those of the dusky savage, belonging to the same collector. These were picked up at Sedan, and have been arranged in a design on a crimson shield. Mr. Cookson has no famous pictures to show his guests. The walls of staircase and gallery are not taken possession of by grim and silent personages, representing the ancestry of families who have been connected with the Manor, nor do the rooms, with their elegant modern furniture, contain much of the painter’s work. In the dining room there are one or two good landscapes, and a figure or two, which are of Spanish or Portuguese extraction; and ever the mantelpiece is a portrait of the father of the present occupier of the house. A number of engravings, of more than ordinary merit, adorn the walls of the billiard room, and the other part of a choice collection of this class of art work is displayed on the walls of a small room, which is used by Mr. Cookson for business purposes. The subjects of these prints are of several classes; the original of one of them belonging to that part of the collection, not on the walls of the billiard room—Bolton Abbey in the olden time—is in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire. In a house, which had been owned and occupied by the representatives of the premier dukedom in the English peerage, and had subsequently been the principal residence of the head of another noble family, one would almost expect to find some traces of former ownership, and a few things, either in the way of pictures, furniture, or books, which would serve to identify the house with those families, who had formerly made it their head-quarters. The Manor House of to-day is destitute of anything of the kind. There is nothing that belonged to the Howards and the Foleys, who lived there for thirteen years, left not a wrack behind, save a solid oak table in one of the kitchens, which, being unstamped with coat of arms or coronet, loses its identity, and it is only guesswork to say that it was formerly the property of the late Duke of Norfolk, or that it was introduced into the house by the late Lord Foley. The house had been empty some time when Mr. Cookson left his Northumbrian home to come to this big unfurnished mansion in Nottinghamshire, and the handsome furniture, with which it is filled, has none of it been in the house for a longer period than that which is represented by the interval between 1874 and the present date.

Worksop Manor, large as it is, only represents, as it were, the shell of its founder’s original idea. If that idea had been carried out, it would, perhaps, have been the largest mansion in England. Until the early part of the seventeenth century, Worksop Manor formed part of the ancient estates of the Talbots. About that time a daughter of the seventh Earl of Shrewsbury married one of the Howards, who was Earl Marshal of England, and by this tie the Dukes of Norfolk became possessed of the Manor of Worksop, together with other property belonging to the Talbots. For many generations it was retained by the Norfolk family, until 1839, when it was sold to the then Duke of Newcastle, who took down part of the house, and divided the park, which was eight miles in circumference, and contained over a thousand acres. This park, which once formed part of Sherwood Forest, it is said, had many unusually fine trees, one of which was 182 feet from the extreme end of its opposite branches, covering more than half an acre of ground.

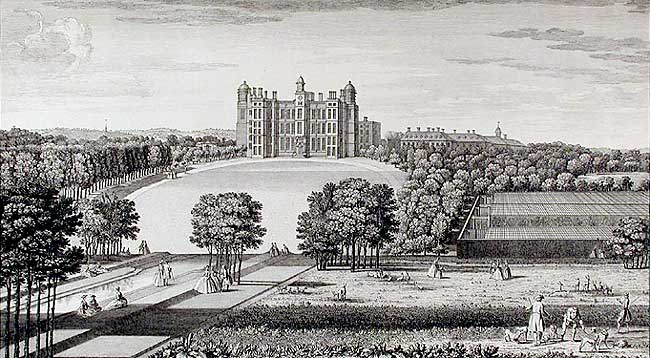

Worksop Manor in the mid-18th century. This house was built in the late 16th century for the sixth Earl of Shrewsbury, and probably designed by Robert Smythson. The building burnt down in 1761.

In the autumn of the year 1761 the original manor house, which contained about 500 rooms, was destroyed by an accidental fire, and damage to the extent of £100,000 was done, a large number of valuables, including paintings, and some of the famous Arundelian treasures, being destroyed. Worksop Manor, Kelham Hall, Thoresby Hall, and, lastly, Clumber, in this county, have all been destroyed by fire at different times. The fire at Worksop occurred at a time when the house was undergoing alterations, which cost the Duke of Norfolk about £22,000.

Worksop Manor in the 1830s. James Paine was commissioned to build a replacement for the Elizabethan mansion. However, only one wing was completed and work stopped on the house in 1767. The wing was demolished in the 1840s.

The building that was designed to replace the one, which the fire had destroyed, was of magnificent proportions. At the Manor I saw a volume of the plans of Mr. Paine, the celebrated architect, with letterpress description of the many noblemen’s residences, for which he had made designs, and among them are the engraved drawings from which Worksop Manor was to be built. It would be difficult to imagine anything more gigantic or elaborate, in the way of house building, than the structure which, according to the plans, was contemplated, and, if death had not interfered, Nottinghamshire would probably have been able to boast the largest nobleman’s residence in the kingdom. Even when a fourth part of the design had been completed, the house was one of the largest in the county, and in this condition it was inhabited. It had a stone facade 303 feet long, in the centre of which was a Corinthian portico, supported by six columns. Some idea of its beauty will be gathered from the following description, which I take from an excellent guide to Worksop and the neighbourhood: —A light and elegant balustrade surrounded the edifice from the tympanum to the projecting part of the ends, which marked the terminations in the style of wings, upon this were placed a series of beautiful vases, executed with great taste. In the centre was a sculptured pediment, on the three points of which were statues ‘Virtue,’ ‘Peace,’ and ‘Plenty.’ The sculpture has been described thus: ‘The three animals denoted some of the well-known ancient alliances of the Norfolk family. They were emblematical the lion is an emblem of strength and courage, the horse of generous ardour, and the dog of fidelity and vigilance. On the west side of the principal group was a distant view of the old Manor House, which, with all the furniture, and the rest of its contents, was consumed by fire, in October, 1761. The evening sun, the broken columns, and the shattered trees, were expressive of the devastation occasioned by the calamitous accident. On the east side, the whole appeared to be unhurt, or restored to its former beauty, which is expressed by the flourishing oaks, the sheep feeding, and the ploughman pursuing his labours. In the foreground of this part was represented the plan of the subsequent building, and some of the instruments employed in erecting the edifice.' The sculptured pediment here referred to, which is of gigantic proportions, stands at the present time in the farmyard attached to the Manor House. It is still in a fairly good state of preservation, and the carved figures are clear and well defined. Something less artistic would have served to keep the poultry within the bounds of the farmyard; but it would be a difficult matter to suggest what should be done with such an unwieldly piece of masonry. The three huge statues, which were formerly placed on the three points of this pediment, now stand in the pleasure grounds in a not altogether perfect state of "repair." Even in its unfinished state the Manor must have been a masterpiece of house architecture, and it is said that some of the finest points were suggested by a celebrated Duchess of Norfolk, under whose superintendence the building was erected. In these days high-born ladies have other ways of spending their time, and architectural enthusiasm can hardly be catalogued amongst their weaknesses. The building has been described as one not unfit for a royal residence, although it has only one side of an intended triangle, which with two interior courts would have completed the plan. The apartments are numerous, elegantly furnished, and many of them very spacious. The furniture and other decorations were all in the ancient style of magnificence, with hangings and beds of crimson damask and sky-blue velvet, and there was a rare collection of tapestry.

The Manor of to-day, though it does not convey any adequate idea of the proportions and design of the Nottinghamshire seat of the Howards, is a building of considerable magnitude, and a convenient residence for a country gentleman who has an income sufficiently large to enable him to keep it up, and a family sufficiently numerous to occupy the many and excellent rooms which it contains. When the Duke of Newcastle purchased the property some forty years ago he caused, as I have said, the greater part of the house to be pulled down. After the lapse of some considerable time it was rebuilt, such portions of the old building that remained being converted into a good residence. For fourteen years the Manor was occupied by Lord Foley, formerly captain of the corps of Gentleman-at-Arms. ‘This nobleman and his amiable lady are still remembered in the neighbourhood of Worksop, and there was a general feeling of regret when they left the country. In front of the house at the present time there is a piece of ornamental gardening which was planned by Lady Foley. It is designed in the form of the Prince of Wales’s feathers, and it is an accurate and elegant bit of model gardening, which is best seen from the windows of one of boudoirs on the second storey. On the removal of Lord Foley from the neighbourhood, the house remained unoccupied for about four years, and then Mr. Cookson became its tenant, introducing bright furniture and a variety of pretty things into the rooms, so that Worksop Manor continues to hold its place among the great houses of this county.

The grounds of the present Manor House are certainly very fine, and no doubt they preserve some of the characteristics which charmed the eye of those who were fortunate enough to have access to them in the Duke of Norfolk’s time, when the house was a centre of princely hospitality and refined festivity. There are some noble trees in the park, and on the lawn in front of the house there is a cedar of right royal dimensions, the diameter of its bole being fully five feet. The lawns are large enough to accommodate half-a-score sets of tennis, and they are kept in splendid order. In the gardens there is always plenty of colour, and from an abundant range of stove houses the Manor is kept constantly supplied with excellent fruit. The vanilla is here grown in as great perfection as, perhaps, it can be grown in England. The pods are of large size and of perfect shape. The kitchen gardens, too, are extensive, and their maintenance requires no small amount of labour and attention. Among the objects of interest to be noticed outside the Manor are four large and beautiful owls—one pair of the snowy variety, and a pair of great eagle owls, beautiful-eyed, large, and ferocious, such as haunt the gloomy pine forests of Norway. They are in excellent condition, their plumage being bright and closely set, and they took perfectly happy in their prison, which is attached to one of the wings of the house. Though they breed here, Mr. Cookson tells me they invariable destroy their young. The stables, coach-houses, and other conveniences connected with this department are built in the form of a quadrangle. A blank wall, about a hundred yards in length, embattled at the top, extends from the house to the gardens, and from the distance looks like a terrace. It is part of the old building, and viewed from the park, its effect is to make the house look larger than it really is. With regard to the mansion itself one is, perhaps, impressed with the idea that with its long corridors, into which so many rooms open, its ample range of offices, which do not represent part of the restoration, and its extensive ground floor, it would be desolate indeed in an unfurnished state. But filled as it is with handsome furniture, and occupied by an English county family, there is no room for such an impression. Perhaps the two brightest rooms in the house are the drawing room, which is furnished in the best of taste, where the effect of a singularly handsome mantelpiece of sculptured marble has not been spoiled by the character of its moveable surroundings, and a boudoir upstairs, which is appropriated by the lady of the house. This room is full of pretty things and on its walls are a number of excellent water-colours, several of which are Mrs. Cookson’s own work.