< Wiseton | Contents | Worksop >

Wollaton

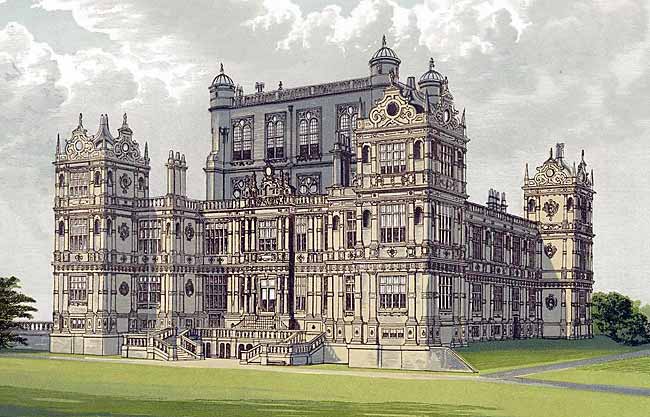

The north and west fronts of Wollaton Hall. The hall was built between 1580 and 1588 by Robert Smythson on behalf of Sir Francis Willoughby. It has been described as the most Elizabethan house in the county and one of the most important in England.

WOLLATON Hall, one of the stateliest mansions in England, has been without an occupant for long intervals during the later years of its dignified existence. It is one of five seats belonging to Lord Middleton, the head of the Willoughbys, and as his lordship cannot well be in several places at one and the same time, he is driven either to the necessity of letting certain of his houses, or of leaving them to the care of servants during most, if not all, of the year. The late peer seems to have preferred one of his Yorkshire seats to any of the four other’s in Nottinghamshire, Warwickshire, or Ross-shire in the North. Probably he was influenced in this choice of residence by sporting considerations; possibly he deserted this county because Wollaton may have been, to his thinking, too near the smoke and busy activity of a large manufacturing town. For this splendid house is now only removed from the borough by a narrow slip of country, and from its topmost places you may almost see what is going on in the heart of the town. But in spite of the near approach of the municipal boundary, Wollaton Hall preserves its county identity amid its baronial individuality. Within its beautiful park, full of noble trees and grassy undulations, the deer roams in as perfect security as do his fellows in the unfrequented recesses of Sherwood Forrest ; timid wild animals feed within the shade of its massive masonry, and the cry of the pheasant issuing from one of the little plantations in the park, or the whirr of a covey of partridges returning from neighbouring stubbles, are sounds and appearances more suggestive of complete rustic retirement and security than of the near-proximity of a busy centre of commerce. Few places that I know, have, or appear to have, advantages equal to those possessed by Wollaton. Here is a house of superb proportions, displaying in its imposing outline all the architectural beauty of a celebrated period, of which but few really noble specimens remain; provided internally with splendid suites of rooms and magnificent staircases, which have been decorated within forms of beauty by the trained and skilful hand of a Verrio; spacious park and extensive pleasaunces, quiet and private; and the life and attractions of a fine town within easy walking distance. But Wollaton Hall was unoccupied at the time of my visit, except by the family portraits, representing, in voiceless array, a long and illustrious ancestral line. For a considerable number of years during the lifetime of the late Lord Middleton, Wollaton Hall was occupied by Mr. Henry Ackroyd, one of a wealthy Yorkshire family, and afterwards by Mr. Douglas Lane, whose tenancy was of short duration. Then again the mansion was empty, it halls silent, and its park unfrequented— Deserted rooms of luxury and state,

That old magnificence had richly furnish’d

With pictures, cabinets of ancient date,

And carvings gilt and burnish’d.

In 1580, in the twenty-second year of the reign of Elizabeth, Sir Francis Willoughby determined to spend some portion of his wealth in building a mansion which should not only serve himself and his immediate successors, but which should remain a magnificent ornament to the landscape, and a great house of the county after the lapse of centuries. In those days the erection of a solid stone mansion suited to the requirements of a man of large estate and of exalted position, was a gigantic undertaking, and the building of Wollaton hall was spread over eight years, much of the time being occupied, I should imagine, by the bringing of time stone from Ancaster, by means of the somewhat imperfect resources available at that period in the history of locomotion. This stone was obtained in exchange for coal, which the estate has always furnished. The superintendence of the undertaking was entrusted to John Thorpe, a celebrated artist of the time, who is said to have died during the execution of this, the last of his important works. It is related that Sir Francis himself was the designer of the plans. The outward features of the building are familiar to many who will read this article. It has repeatedly been described as square with four large towers adorned with pinnacles ; and in the centre the body of the house rises higher, with projecting coped turrets at the corners. The front and sides are adorned with square projecting Ionic pilasters, and at intervals appear niches filled with busts of philosophers and other distinguished personages. Upon what information Camden stated that the building of this magnificent house sunk three lordships it would perhaps be impossible to discover, but it is pretty certain that the immense cost of the mansion must have proved a rather heavy drain upon the large resources of Sir Francis Willoughby, during the eight years over which its erection extended. The work, three centuries ago, was done with such completeness and within so adequate a view to the requirements of successive generations of a distinguished family, that very little in the way of alteration has been effected during that long period of time. The great hall has been altered to suit the taste of one of the Willoughbys, but in its general aspects the building is pretty much what it was when, on its completion in 1558, Sir Francis Willoughby went out into the park to get an advantageous view of its imposing proportions.

The Great Hall at Wollaton Hall, pictured in the early 20th century.

The great hall is celebrated throughout the county no less for the beauty of its architecture and ornamentation, than for the masterpieces of art which are ranged upon its walls. I am informed that the pictures at Wollaton only represent a portion of Lord Middleton’s collection, though they are probably not the least valuable. Let us glance at a few of those in the great hall, and then take a hurried look at some of the pictures which adorn the walls of other apartments in this unoccupied mansion. In the great hall, with its beautiful screen supported by Doric pillars, and rich in ornamentation, the masters are represented. On these spacious walls which are so liberally lighted that none of the painter’s art is lost to view, are three of Snyders’ masterly compositions, representing various stages of the boar hunt, and showing all the life and spirit which that great artist put into his animal creations. At the end of the hall opposite the gallery and organ, flanking a large painting of Diana and her nymphs, which has been recently introduced, hang Neptune amid Amphitrite, and Jupiter and Europa, the work of Luca Giordano, the disciple of Spagnoletto, who deceived the ablest connoisseurs by his unrivalled powers of imitation. This clever Neapolitan had a weakness for mythology, and these two pictures are perhaps as good examples of his surprising freedom of hand and agreeable tone of colour, as is his rendering of the contest between Perseus and Demetrius which once adorned a Genoese pelazzo. The Boar Hunt, by Abraham Hondius, which has a place in this part of the collection, illustrates the universality of this painter’s art, landscape or animal life being equally easy to him, and is worthy of the great Snyders himself. Here, too, are three admirable examples of the genius of Philip Roos, better known in the world of art as Rosa da Tivoli, who once painted a picture of sheep and goats in less than an hour to win a wager for his patron, an Imperial Ambassador, and received a considerable portion of the proceeds as a reward for his rapidity of manipulation. These three pictures are a herdsman and his flock, showing that skilful grouping for which the artist was noted; horses and cattle, and the well-stocked interior of an Italian kitchen. A large and very fine picture in another part of the hall, of lions disputing the possession of prey, is attributed in the catalogue to Rubens. Three of the great hall pictures, two pastoral scenes, and one named "Hunting time Wolf," are evidently the work of a master brush. They were purchased by the fifth Lord Middleton, and are supposed to have been brought from Italy by a person of distinction and judgement. The large picture of Charles the First is not by Vandyck, but it is a copy of that master and a striking portrait. Several of the pictures in the great hall possess a local interest. There is an excellent picture of Lord Howe’s action, presented to the seventh Lord Middleton, who was first-lieutenant on board the "Culloden" in the celebrated action off Ushant; there is another bearing the date 1695 depicting the beautiful landscape about Wollaton and signed by Sibrects, and over the fireplace is a portrait of Sir Francis Willoughby who built the house, and whose portrait by Zucchero hangs in the adjoining saloon. In this smaller saloon one gets an introduction to some of the earlier members of this old family, and is able to learn something of its lineage. Among this goodly company is Bridget, eldest daughter and co-heiress of Sir Francis Willoughby, who married Sir Percival Willoughby of the house of D’Ersby, and brought to him the greater part of her father’s large estates. I do not know whether this is the same Sir Percival whose portrait looks at one from these walls and is backed by a strip of paper stating that its subject was "Lost by words, not winds or waves," a pictorial epitaph, if one may call it by that name, which is supposed to refer to his having been ruined by law-suits, as many another has been ruined both before and since. There was a Sir Percival Willoughby who represented the county of Nottingham in the first Parliament of James the First. The portrait of Thomas, the first Lord Middleton, is by Sir Godfrey Kneller. This gentleman served in six several Parliaments during the reigns of William and Anne and was ennobled in 1711, from which year the peerage dates. The portrait is associated with that of Cassandra, who was sister to the first peer and married the Duke of Chandos. Among the other portraits in the saloon are those of the fourth Lord Middleton, Prince William of Orange, and Letitia, daughter of Sir Francis Willoughby, who married Sir Thomas Wendy, a lady possessing not only many virtues and good qualities, but also considerable learning and attainments, and the subject of a dedicatory poem by one of the songsters of the time. There are, with these, other family portraits, and one of the young Prince of Bavaria. In company within these portraits hang Rubens’ picture of Achilles, discovered in the Court of Lycomedes, whither he had been sent by Thetis in the disguise of a female, in order that he might escape being pressed into the Trojan War, in which he was afterwards to display so much bravery. This incident in the history of the Grecian hero was a fit subject for such a master as Rubens ;— Ulysses in the guise of a merchant offering jewels and arms to the disguised hero, and discovering his sex from the choice he made. The feminine gauds, brilliant and glittering, were contemptuously rejected by the warrior who was to slay Hector, and himself to die of a wound inflicted in the only vulnerable part of his person. In the dining room there is a wonderful picture of dead game, with lobsters, oysters, and other delicacies of the table, and a large and somewhat singular composition by Sibrects, who has contributed largely to this collection. Into this the figure of a girl with a basket of freshly cut flowers is introduced. She appears suddenly to have come upon this lavish display of nature’s substantial gifts, and to have forgotten her flower mission in the contemplation of an abundance of fish in which has just been taken from its element, and fruit and vegetables which have recently been removed from the parent stem and from mother earth. Here, among drolls and conversations and pieces of still-life by seventeenth century artists, is a further array of portraits. There are half-lengths of the sixth and seventh Lords Middleton by Barber, who was, I believe, of Nottingham origin; of Sir Nesbit Willoughby, who host an eye whilst fighting for his country; of Sir Francis Willoughby, whose son was to become a scholar and philosopher, and of Lady Cassandra, a daughter of the Earl of Londonderry, who was married to Sir Francis. Among the other pictures in the room is a very amusing one by Sibrects, to which attaches a little story that is worth relating. It represents two boys eating hasty-pudding—a compound which is not often heard of in these days—and the larger boy has thrown a quantity of the mess into the eyes of his lesser brother. The injured youngster is crying lustily ; the other is very much pleased with his performance and is preparing to make a further distribution of pudding in the same direction. It is said that one of the late lords of Wollaton ordered this picture to be painted after he had seen the village boys quarrelling over their food which happened to be hasty-pudding. There is a characteristic painting of Hemskerck’s—twojovial colliers, playing at cards. It shows that abundance of humour and lively and ‘whimsical imagination, which Hemskerck’s best known works display, and was probably painted during the period of his settlement in London. This is not the only painting by this whimsical Dutchman, which is to be seen in the Wollaton collection. The sick woman and her doctor, and a devout person saying gin-ace before meat are attributed to him, and very likely some of the other smaller paintings which have been left to be taken care of here, are from his brush. There are also here several valuable and interesting illustrations of Dutch life—one a woman selling slices of salmon, for which she is evidently asking an extravagant price, of a lady whose notion of housekeeping is more frugal than that of David Copperfield’s Dora; another, a smaller one, a Dutch vegetable market by Palamedes. The great hall and the dining room claim the most interesting portion of the Wollaton collection of paintings, but as their position in the house is changed from time to time reference to their particular whereabouts will not assist in their identification. It must also be borne in mind that I am not attempting to furnish a catalogue of the Wollaton pictures. To do that successfully, one would need to spend more than a couple of hours in these rooms, but as the house is closed to the public, it seems to me that I might occupy most of the space allowed for this article with some of the impressions left by a brief inspection of dine rooms and galleries. Among the pictures not already mentioned, is a scripture piece by Rubens, the Shores of Capernium, painted on panel; a view of Middleton Hall, the Warwickshire seat of the family, and a number of portraits. Among these is one of Sir Hugh Willoughby, who perished in the North Seas, in 1553. He went out for the purpose of making discoveries in the Northern Ocean, with three ships fitted out at the private expense of the Society of Merchants, who had formed a company, in order to prosecute the search after a northeast passage to India. At Spitzbergen, one of the ships was separated from the others. Soon after the separation, Sir Hugh is said to have discovered land, but was unable to examine it on account of the iceflow. Sailing westward he came to a river and harbour where he decided to pass the winter. Here he and his whole crew perished, being unable to endure the hardships of that dreadful latitude. The portrait of Sir Richard Willoughby, who was Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas for the space of twenty-eight years, is also in the collection ; as also are those of Sir Francis Willoughby, the first baronet, who built the fine stables at Wollaton in 1774, of Sir Francis Willoughby, the philosopher, of Lord Strafford and his secretary, which, along with several other pieces of the kind throughout the country, claims the mede of originality; of the second Lord Middleton in his Coronation robes, by Sir Joshua Reynolds; of Sir Thomas Wendy, who married into the family, and others.

The painting of the grand staircase—the most interesting portion of the house—is said to have been done by Verrio, who charged enormously for the numerous works which he painted in England, though few of his magnificent frescoes remain with us. At Chatsworth and at Burleigh there are to be seen examples of his superb art. The staircase is situated on the north of the building on the ceiling Prometheus is represented stealing the fire from heaven in the presence of the gods and goddesses, who express their amazement at the sacrilege, while the walls are richly decorated with incidents from mythological history, painted by the same distinguished artist. These are some of the principal pictures which are to be seen by the rare visitor to Wollaton Hall, who, if his visit happen on a favourable day, will be pleased with the appearance of the park and grounds viewed from the windows.

In a county which possesses few really fine houses, Wollaton must always be regarded as a conspicuous and handsome piece of architectural ornamentation, and a splendid proof of the taste which prevailed in the Elizabethan era. Perhaps if a house of that size and pretention could be built in these days, the internal arrangements might be somewhat different to those which exist at Wollaton to-day. The principal rooms would probably be made larger, and perhaps less attention would be paid to inward ornament, But, be this as it may, the praise which the sight of Wollaton Hall, standing bold and ornate, upon a commanding eminence, drew from one who does not often colour his relation of historical facts with rapturous outbursts, is not ill-bestowed. "Lovely art thou, fair Wollaton, magnificent are thy features ! In years now venerable thy towery-crested presence eminently bold-seated, strikes the beholder with respectful awe. Unlike many of the visionary building edifices of the present day, designed with but little variation of style and uniform in disordering architectural order, thee we must admire, chaste in thy component part, and possessing an harmonious whole.