< Clifton | Contents | Colston Bassett >

Clumber

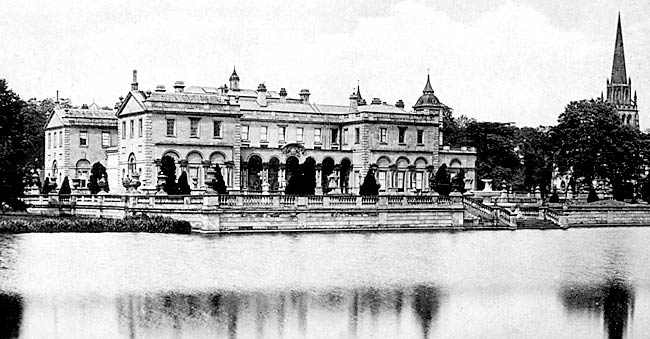

Clumber House and church from the lake, c.1900.

IN 1879, Clumber House was partially destroyed by an accidental fire, and pictures and other things of immense value, which can never be replaced, perished in the flames. This fire happened just fifty years after the destruction of Nottingham Castle in the Reform Riots. Both the Castle and Clumber belong to the Duke of Newcastle, so that the family has suffered considerably by disasters of the burning order. But their rent roll is vast, and if the Dukes of Newcastle cannot buy pictures like those which were destroyed in the last fire, they have been enabled to rebuild their house on a sufficiently magnificent scale, and at a very considerable cost to repair the damage that had been done to brickwork and masonry and to internal decorations. Perhaps no home of title in the whole county is so well known as Clumber. Its owners have been men of high rank, great wealth, and mostly of power in the State, and they have allowed the public to visit their house at certain times of the year, and to see the treasures it contains—a house which for size and situation can hold its own with any of those other palaces that are occupied by the wealthy of this land, and treasures the like of which the riches of England would not purchase. The Dukes of Newcastle have been patrons of art and collectors of the best work of painters, ancient and modern, and the Clumber collection is celebrated in the art world and in the country. Visitors to the Castle Museum at Nottingham have had the privilege of seeing some of the choicest of the Clumber treasures, and it would have been a fortunate thing for the noble owner and his successors and for the country at large if the whole of the collection had been stored in those galleries when the late disastrous fire broke out.

The mansion, which stands on what was once a waste of forest land, was built in 1770 of white freestone, which was brought from a quarry on the Duke’s estate five miles away. At that time it was said that no nobleman in England possessed such a princely abode. Its situation was unique; the lake facing its central front added a decided charm to its outward appearance, and its architectural advantages and great size gave it claims to be classed in the first rank of the stately homes of England. The house originally consisted of three fronts, the centre one facing the water, containing a light Ionic collonade; and looking at the building from the elegant bridge which crosses the lake, its appearance was most pleasing.

The lawns then, as now, were very fine, smooth, velvety, and of the richest colour, descending by terraces to the lake and fringed with thriving shrubberies. The park compasses eleven miles, and was once part of a forest which had hardly been explored. It is now surrounded by venerable woods, which are seldom trodden, except by deer and small wild animals. From the windows of the house you can see these noble woods, with their acres of sturdy vegetation ; but the attention is necessarily taken up with the beautiful and costly things arranged in the various rooms through which one is shown. A day could well be spent in studying the Clumber china; it would take a longer time to do justice to all the pictures. The art treasures of Clumber enjoy a celebrity which has reached far and wide.

The collection of family portraits contains a long line of nobles, some of whom have been illustrious in the service of the State, whilst others have held local appointments, to the discharge of the duties in connection with which they have brought the intelligence, and the highmindedness that distinguished their race. At various times the collection has been enriched by the addition of works of art acquired by purchase or brought into the family by marriage. To name them would involve the publication of a list of almost all the great painters whose canvasses are famous in the galleries of the nations. There are examples by Rubens, Gainsborough, Hogarth, Reynolds, Snyders, Vandyke, Lely, Gerard Douw, Guido, Poussin, Claud Lorraine, Rembrandt, Ruysdaal, Salvator Rosa, del Sarto, Titian, Holbein, Creswick, Jansen, Teniers, Kneller, Dominichino, and a host of’ others. Some of these pictures, and not the least valuable of them, perished in the catastrophe of 1879. It is not often that such celebrities as these can be got together under one roof. Sigismunda weeping over the heart of Tancred, a picture which in the Clumber catalogue is attributed to Corregio, and was once the property of Sir Luke Schaub, is said by some to have been the work of Furino. It was this subject that Hogarth is said to have chosen for the purpose of showing that the praise bestowed upon the ancients was the result of prejudice, and his effort thus to compete with the dead was coarsely criticised by Horace Walpole, who likened his Sigismunda to a common courtezan, "with eyes red with rage and usquebaugh, tearing off the ornaments her keeper had given her." Guido’s Artemisia, with the cup containing the ashes of her husband, has generally been regarded as a companion to the Sigismunda in the Clumber collection, in which the touches of Michel Angelo’s genius are not wanting. The house is large enough to hold all these valuable paintings, and they are distributed over rooms which have long been famous for their size and beauty. The State dining room, sixty feet in length, and thirty-four in breadth, and designed to accommodate one hundred and fifty guests at table has been described as one of the glories of Clumber, with its rich ornamentation and ornate fittings. On these walls were placed the four Market pieces by Snyders, the two landscapes by Zuccarelli, and the large painting of dead game by Wenix. The library was admired by everyone who visited Clumber under the old regime, on account of the light and elegant gallery round the upper part of the room, and the highly decorated ceiling. Here Westmercott’s superb statue of Euphrosyne found a home, as also did Bailey’s Thetis and Achilles, and many valuable bronzes, besides an extensive collection of rare old books, to say nothing of modern literature. Among the Clumber statuary the most celebrated pieces, besides those already mentioned, are a large figure of Napoleon, which some say is the work of Canova, whilst others set it down to Franzoni, purchased at Cararra in 1823; Bailey’s statue of Thompson and busts of the Duke of Newcastle by Nollekens; Sir Robert Peel, Cromwell, and others.

Among the pleasure-houses of England very few can rival Clumber in pictorial and sculptural wealth, and like those other houses in the Dukeries it deserves to be ranked amongst the greatest houses of the country. The house was built in 1770, but successive owners have altered it. It stands, as I have already said, upon what, at the time the plans for its erection were being designed, was a dense forest covered with great trees and sturdy growths of bracken and heather. At enormous expense the then Duke of Newcastle reclaimed the land, and formed a lake, a small undertaking which cost him £7,000. In the re-building the aspect of the house has necessarily been somewhat altered, but it has not changed so as to subordinate the west front, which is still the most imposing part of the building. In the gardens flowers blossom in geometric beds; there are still graceful statues in the grounds, and from the terraces and from some of the principal rooms you look over this lake of some ninety acres, where the water-fowl find a home, and where the pike fatten which afford sport for the young Duke.

The head of the Pelham-Clintons, and the owner of their vast estates, which have been somewhat impoverished during the last generation, is a young nobleman, who was born no longer ago than 1864. His father died in the prime of life, and left the Earl of Lincoln, who was then a public schoolboy, the possessor of a great name and an estate, which in Nottinghamshire covers 34,600 acres of land. In 1641 the annual value of the Newcastle estates was, Nottinghamshire £6,229, Lincolnshire £100, Derbyshire £6,128, Staffordshire £2,349, Gloucestershire £1,681, Somersetshire £1,303, Yorkshire £1,700, Northumberland £3,000; total £22,390. The rent roll now is considerably more than that sum, and in time it may reasonably be expected that it will be still further increased. For the origin of the family name—Pelham-Clinton we have to go to the reign of Edward the First, during whose sovereignty the lordship of Pelham belonged to a certain Walter de Pelham, who died in 1292. In the reign of the third Edward, John de Pelham was a famous person, whose figure in memory of his valiant acts was painted on glass in the Chapterhouse of Canterbury Cathedral, of which he is said to have been a considerable benefactor. He was one of those who took the French King prisoner at the Battle of Poitiers. The son of this celebrity was scarcely less distinguished than the father, and amongst the offices he held were those of treasurer to the King and ambassador to the King of the French. Many of the Pelhams of succeeding generations were famous, and held high places, and the family was ennobled in 1706. The second Lord Pelham, by the will of his uncle, John Holles, Duke of Newcastle, was made his heir, and was afterwards created Duke of Newcastle and a Knight of the Garter. His brother dying without surviving male issue, the estates passed to Henry Clinton, Earl of Lincoln, who assumed the additional name of Pelham, his mother and his wife being both of that name. The Clintons had been settled in England since the Conquest, and took their name from a place in Oxfordshire. One of them was Bishop of Salisbury as early as 1228, and another was summoned to Parliament, under the title of Baron Clinton, in the reign of Edward the First. The second son of this noble was Lord High Admiral of England in 1333, and an earldom was conferred upon him—that of Huntingdon. His successors distinguished themselves in the wars of three reigns, and in 1572 the Clintons became Earls of Lincoln. The second of these earls was one of the commissioners at the trial of Mary Queen of Scots, the seventh was Constable of the Tower and Paymaster of the Forces in the reign of Queen Anne, and the ninth became Duke of Newcastle.

Of the Dukes of Newcastle the most distinguished were the first and the fifth. William Cavendish, first Duke of Newcastle, succeeded to the estates of his father in 1617. Three years later he was raised to the peerage as Baron Ogle and Viscount Mansfield, and in 1627 he became Earl of Newcastle. He is said to have been a man of retiring disposition, but of considerable attainments, and the King had such a high opinion of his character and his worth that he placed his son under his especial and immediate care. At that time the Cavendishes, of which family the first Duke of Newcastle was the head, resided at Welbeck and Bolsover Castle, and more than once these places were visited by the Sovereign, who was entertained with becoming splendour—entertainment which cost the Earl between £14,000 and £15,000. The popularity of the Earl was unbounded, and at one time or another he raised as many as 80,000 men to fight in the service of the King. But the storms of martial warfare and the worry of political conflict were little suited to the tastes of this nobleman, who infinitely preferred the arts of peace. He was a ripe scholar, was very fond of the fine arts, and was, according to Clarendon, a very fine gentleman. Hume describes him as an ornament of the Court, and of his order, and says he took up cudgels on behalf of the misguided Charles merely from a high sense of honour and a personal regard to his master. He paid dearly for his elevation to the dignity of a dukedom. When he returned to his estate, after the wars were over, he found that his parks, with the exception of Welbeck, had been destroyed and plundered of their game, and his losses have been estimated at no less than £700,000. But fortune favoured his successors, and the possessions of the family have been augmented in a variety of ways. The Park property, then a part of Sherwood Forest, was bought of the Earl of Rutland. The fifth Duke of Newcastle was a most distinguished man, and when he was in office many important documents were dated from Clumber. He was successively Lord Warden of the Stannaries, Chief Secretary for Ireland, Secretary of State for the Colonies, and Secretary of State for War. Of him the late Miss Martineau, writing his memoir in 1864, states "No statesman of our time has won a more universal respect and regard, and few Ministers of any period could be more missed and mourned than he will be by good citizens of all parties and ways of thinking …Those who were nearest to him were subject to frequent surprises from his simplicity, his unconcealable, conscientious, and abiding sense of fellowship with all sincere people, whoever they may be. As a nobleman of aristocratic England, he was in this way a great blessing, and a singularly useful example."

The site of Clumber House (demolished in 1938) and the chapel from across the lake (photo: A Nicholson, 1994).

< Clifton | Contents | Colston Bassett >