< Bramcote | Contents | Chilwell >

Bunny

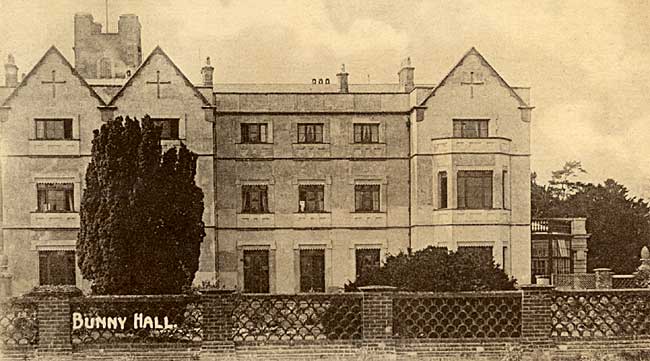

The south front of Bunny Hall in the early 20th century.

BUNNY Park hall, a mansion of considerable importance, is owned and occupied by Miss Hawksley, niece of the late Mrs. Forteath, to whom the estate was bequeathed by Lord Rancliffe, the last of the barons of that title. The property originally belonged to the Parkyns, an old and distinguished family whose estates seem to have got into other hands, or to have been worn away by the friction of legal machinery. The baronetcy is still maintained, but the title does not carry any large rent roll. The family of which Sir Thomas Parkins, baronet, is the head, can claim long descent, and a distinguished and protracted connection with this county. Towards the latter end of the sixteenth century Richard Parkyns, Recorder of Nottingham and Leicester, who was by no means dependent upon the emoluments of his office, purchased the manor of Bunny, then as now of considerable extent. His descendant, Mr. Isham Parkyns, also of Bunny, held the rank of colonel during the Civil Wars, and in consideration of the determined and courageous resistance he offered to the power of the Usurper, which is said to have implied his own impoverishment, his son was created a baronet in the year 1681. In 1795, little more than a hundred years later, the family acquired a higher rank, and Thomas Boothby Parkyns was made Baron Rancliffe, an Irish peer. On the death of the second Lord Rancliffe, in 1850, who succeeded to the Bunny estates, the peerage became extinct. By marriage the family is connected with several distinguished and titled houses. Mr. Mansfield Parkyns, who formerly lived at Woodborough Hall, married a daughter of Lord Chancellor Westbury, and one of the daughters of the first baron was espoused to Sir Richard Levinge, an Irish baronet.

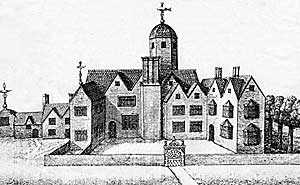

"Bunney House" in 1676.

George Augustus Henry Anne Parkyns, second and last Baron Rancliffe, who died at Bunny Park, has not been dead long enough to be forgotten by Nottingham people. His political connection with the county town was as memorable as that of the late Sir Robert Clifton, and between the two there is something in common. For a long period Lord Rancliffe represented Nottingham in Parliament, and his popularity was as remarkable as it was long-lived. At the age of fifteen he was the bearer of a title and the possessor of very considerable property to which he subsequently contrived to add the ancient belongings of the Parkyns family. The newly fledged lordling was brought up into the immediate care of Lord Moira, who considered that he could have had better training than that to be obtained in a fashionable regiment. On his marriage with the Earl of Granard’s daughter, the young lord left the army and became equerry to the Prince of Wales, afterwards George the Fourth. As soon as he reached manhood’s estate, Lord Rancliffe was returned to Parliament for Minehead, under the good old system of purchase which obtained them. Lord Rancliffe sat for this place for seven months, and it is said that his constituents never saw him or knew what lie was like. In 1812 there was a vacancy in the representation of Nottingham on the resignation of Mr. D. P. Coke, and a number of persons interested in the election went to Bunny, and induced Lord Rancliffe to stand in the Whig interest. A sharp contest ensued, and Lord Rancliffe was returned, his success being largely due to the influence exercised upon the constituency by Lady Raneliffe. The other successful candidate was Mr. John Smith, who was returned at the head of the poll. In 1818 and again in 1826, Lord Rancliffe was returned for Nottingham, and he did not withdraw from Parliamentary life until four years later, after representing the borough for twenty-eight years. He died at Bunny, in 1850, at the age of sixty-five, and of him, one of the principal biographers says:—" Lord Rancliffe was what might be considered a good party man, but by no means a good political leader. He was neither fitted by natural endowments, nor yet by the habits he cultivated for the post of a leader; still his views were sound and constitutional on most political subjects, and his votes, which were uniformly in accordance with his professions, were calculated to advance the cause of social progress and the diffusion of civil and religious liberty throughout the world."

The castellated tower of Bunny Hall was probably built as a belvedere, overlooking the deer park (photo: Andrew Nicholson, 2003).

There is very little at Bunny to remind one of Lord Rancliffe’s connexion with the house. Either lie or those who followed him evidently contemplated enlarging the place, and commenced the necessary alterations. But the plan was never carried out, and Bunny is an unfinished mansion at the present time. The introduction of a new staircase or flight of steps was contemplated, and amongst the litter of a partially finished apartment there are some of the pieces which were to form this new work, so long since abandoned. Not that Bunny Hall requires any enlargement. It is a large and spacious mansion with, on the ground floor, a continuous suite of rooms said to be among the biggest in the whole county. These, the drawing room, the library, and the dining room, are entered from a long corridor lighted from above, terminating in a billiard hall, and ornamented at intervals with glass cases containing birds. In one ease is an albatross; in another the graceful form and exquisite plumage of a flamingo. At the end of the suite of rooms is a small conservatory opening into the drawing room, which is furnished in sumptuous fashion. The walls are decorated with graceful designs and in lively colours, and the furniture is bright and elegant. There are some rare old cabinets here, amongst them a Louis Quatorze and one of Florentine Mosaic, and some valuable pieces of china. The fireplace is the work of Italian artists. It is supported by slabs of marble of exquisite purity, bearing on either the perfectly sculptured form of some beauteous goddess. Both drawing and dining rooms are destitute of pictures ; it was never intended that those walls, so expensively and artistically decorated, should be hidden by picture frames. In the dining room there is another fine cabinet and a number of quaint high-backed chairs, which are said to have been made and carved in the reign of Elizabeth. The windows overlook a square of cheerful gardens enclosed by a low and open wall. The library is between the drawing and dining rooms, and there are in it a great number of books. On one of the tables there is a small bust of the First Napoleon, engaged in sketching a plan of the battle of Marengo. A special value is attached to this ornament. The house contains a number of portraits, about which one is able to get but little information. They are all of them said to be members of the ancient family of Parkyns, and one which hangs over the antique mantelpiece in the billiard hall, a gentleman in armour, may, perhaps, be safely described as that of Mr. Isham Parkyns, who took such a prominent part in the Civil Wars. Possibly Vanderbank’s portraits of Sir Thomas and Lady Parkyns are among the collection, part of which has been consigned to the housekeeper’s room. The family, of which these portraits remind one, at one time had great influence in the county. They were settled in Berkshire before they came here, but they should certainly be classed among the old Nottinghamshire families. One of them, buried in the fine old church at Bunny, the Sir Thomas Parkyns of the last century, was an extraordinary man. He was a great wrestler, he studied physic for the benefit of his neighbours, and he wrote in dead and living languages. He distributed scraps of Latin over the parish with becoming impartiality, and tombstone and horse block were alike inscribed with the language of Maro and Flaceus. It was his mission to encourage the spread of muscular Christianity, and to give a classic turn to bucolic life. The whimsical epitaph on his monument is not inappropriate, applied, as it is, to a worshipper of muscle, who once said, "I receive no limberham, no darling sucking bottle who must not rise at Midsummer until eleven of the clock, till the fire has aired his room and clothes of his colliquative sweats, raised by high sauces and spicey forced meats, where the cook does the office of the stomach with the emetic tea table set out with bread and butter for breakfast; I’ll scarce admit a sheepeater none but beefeaters will go down with me." The Parkyns’ were good friends to Bunny. When they lived at the hall they built and endowed schools and almshouses in the parish, restored the church, and they are said to have dispensed charity and hospitality with a lavish hand. What is generally called a tower gives an imposing appearance to Bunny Ball. This is an elevated piece of brickwork, which in the distance looks like the tower of a church. It rises to a considerable height, and from its summit, which is reached by an oak staircase, you may see objects that are very far away. The brickwork is old and it is evident that the house is old too. On the front of the brickwork is a coat of arms, and the date recorded on the stonework is 1723. The lower part of the tower is ivy-grown, with here and there some odd sprays of ragwort.