< Previous | Contents | Next >

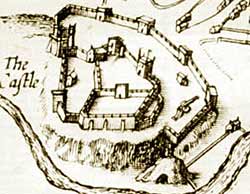

Nottingham Castle as depicted on John Speed's map of Nottingham, 1615.

The history of the castle itself is associated with one of the most daring intrigues, the details of which have come down to us from the age of chivalry and romance. Edward II., in his visits to Nottingham, was usually accompanied by his Queen, Isabella, who became enamoured of Roger Mortimer. The faithless consort and her paramour plotted the death of the King, and their machinations resulted in his dethronement, hired ruffians completing the horrible scheme by killing him in a barbarous and cruel manner.

A regency was formed during the youth of Edward III., and Mortimer gained the ascendancy; but on the King attaining his eighteenth year, he, with some of his Barons, formed the design of reducing the usurper’s power. About Michaelmas, 1330, a Parliament was summoned to be held at Nottingham; but the castle was occupied by Queen Isabella and her favourite, attended by a band of 180 knights. A project was formed for getting Mortimer into the custody of the King and his followers, but this was no easy task, for the castle was strictly guarded, and every night the Queen deposited the keys beneath her pillow. The effort must have proved costly, if not abortive, had not the constable of the castle, William Eland (deputy of the governor, Richard de Grey, Lord of Codnor), rendered assistance, and undertaken to lead a party into the castle through a secret passage known to-day as Mortimer’s Hole. With his connivance, Mortimer was seized and put under arrest, and with some of his adherents was sent to the Tower. The Parliament summoned to meet at Nottingham was adjourned to Westminster, where he was impeached and ordered to be executed—a sentence which was carried out at Tyburn a few days afterwards.

Nottingham was the scene of the meeting of Parliament in 1336, when subsidies were granted to carry on the war in Scotland and on the Continent. In the reign of Richard II. a council was held in 1387, whereat the King formed the design of packing the Parliament with creatures favourable to his own purposes. This unconstitutional proceeding was successfully resisted, but the Mayor, Sheriffs, and Aldermen of London were subsequently ordered to meet the King at Nottingham and give a reason why the city would not raise a loan for his wars. Once inside the great stronghold, the City-fathers found themselves captives, and only, obtained their release upon a reconciliation between them and their royal master. Again in 1397 the castle was made the place of a State council, when the Duke of Gloucester and the Earls of Arundel and Warwick were impeached for high treason.

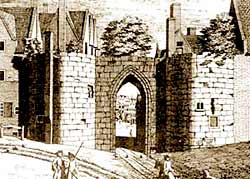

Nottingham's town wall: the medieval Chapel Bar, demolished in 1743.

The Corporation records show that Henry IV., who granted the town a charter in 1399, was present at a trial by battle here which took place on August 12, 1407, and an account of which may be found in letters printed in Rymer’s ‘Foedera,’ viii. 5 38-540. Henry V. granted a confirmatory charter in 1414, and a further charter with additional privileges was given by Henry VI. in 1448. The town had been very loyal to the King, assisting him in all his movements, and raising money on a lease to furnish soldiers to aid him in dispersing the rebels under Cade. The Corporation records also contain an interesting document ‘relating to the passing of Lancastrian lords through the town when Henry VI. was gathering his forces against the leaders of the Yorkist party.’ In 1464 Edward IV. and Warwick, the King-maker, of whom Lord Lytton gives so graphic a picture in ‘The Last of the Barons,’ passed through the town on their way to repel Queen Margaret’s incursions, and there are entries of presents made to them and their principal adherents. ‘Item paied for xx galons save oon of rede wyne giffen to the Kyng on his beyng here, the Thursday next after the fest of Epiphanie, etc., price of evry galon viijd. summa xiijs.’ Sundry gallons of wine were also given to the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chamberlain, and the Earl of Warwick, the grant to the last-named dignitary being only three gallons, while in the case of the Chief Baron of the Exchequer the quantity was reduced to one gallon. Years afterwards, when Warwick and Edward had parted company, Henry had been restored to the throne, and Edward, returning from his flight, was gathering an army to win back for himself the crown, Nottingham became a rallying-place for Edward’s friends. Edward reached the town on March 23, 1471, and was there joined by a compact body of 6oo men-at-arms under Sir James Harrington and Sir W. Parr. The rival forces met at Barnet, and the King - maker’s body was among those that strewed the fatal field. Edward IV., who had received such liberal aid from Nottingham, died in April, 1483; and Richard III., to whom the town was equally faithful, arrived here the same month, the period of this eventful reign forming a notable era in our local annals.

Nottingham Town Hall in 1741 (Throsby, 1790)

Nottingham Town Hall in 1741 (Throsby, 1790)The town or guild hall, then known as New Hall, at Weekday Cross, had just been constructed, and a number of workmen had been busily engaged in improvements at the castle. The additions which had been made included the erection of a strong tower on the eastern side of the fortress, and when the works were completed by Richard the castle was one of the most commodious and magnificent in the kingdom. Hutton says, and it is at least a pleasing tradition, that Richard was fond of Nottingham Castle, often resided there, and erected a turret on an eminence, and called it the Castle of Care. As Mr. Collinson poetically describes it

‘A tall tower watching o’er the widespread plain,

And seen from Charnwood’s hills and Belvoir’s heights,

The crafty Gloucester built, and here again

He longed for daylight after sleepless nights.

"Castle of Care" he named it, and a cloud

Of guilty memories ever o’er it loomed,

Dark as the birthplace of the thunder-cloud

That threatening hangs above a city doomed.’

From Nottingham the King, when the brutal murder of the young Princes had been effected, started on a tour through the northern counties, and with a view to stir up a good reception for him at York, a letter was written by his Secretary to the Mayor, Recorder, Aldermen, and Sheriffs of the city, recommending that the streets through which the King’s Grace should pass should be hung with ‘cloths of arras, tapestry work, etc.,’ and hinting that if these things were duly attended to, the Secretary would not forbear calling on his Grace for their welfare. The letter had the desired effect, and his Grace met with a grand reception. Whether he repaid the enthusiastic loyalty of the citizens we do not know, but he does not seem, bad as he was, to have been altogether insensible to the promptings of gratitude. A copy is preserved of a license which he granted to a yeoman of Nottinghamshire, giving him permission to ask alms because ‘he had had two of his barns full of corn and other his goods during his being in the King’s service at Dunbar, in Scotland, by misfortune and negligence, suddenly burnt, to his utter desolation and undoing.’

On March 21, 1484, the King was at Nottingham, when the subject of the relations between this country and France occupied his attention. To the Bishop of St. David’s he gave power to conclude a truce, but overtures led to no immediate result. His Majesty remained at Nottingham about a month, during which time he received intelligence of the death of his only legitimate son, Prince Edward, to whom at the beginning of the year he had caused the Lords to swear allegiance as heir-apparent. A few months after this bereavement the King endeavoured to come to terms with Scotland, and sent ambassadors to the Scotch King, giving him to understand that he was willing to offer peace on every honourable condition, to be confirmed by an alliance of marriage. From Mr. Gairdner’s ‘Richard III.’ we extract a narrative of what followed, and we feel all the more interest in giving the quotation fully, inasmuch as it contains the particulars of an important conference at the castle, hitherto unnoticed by our local historians: ‘The King of Scots received the proposal with great satisfaction, and named in July the members of an embassy whom he proposed to send to conclude peace at Nottingham in the beginning of September. These were men of the highest weight in his kingdom: The Earl of Argyll, who was at this time Chancellor of Scotland; William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen; Lords Lisle and Oliphant; John Drummond, of Stobhall; and the King’s own Secretary, Archibald Whitelaw, Archdeacon of Lothian. Richard in reply sent a safe-conduct for them, and the plenipotentiaries met with the King himself at Nottingham on September 12. The conference was opened in the great chamber of Nottingham Castle. The proceedings commenced by Whitelaw addressing the King in a polished Latin oration full of high panegyric, which it is unnecessary to notice, except for a rather interesting passage bearing on Richard’s personal appearance, and indicating that he was small of stature. The speaker quoted and applied to the King what was said by the poet of a most renowned Prince of the Thebans, that nature never enclosed within a small frame so great a mind, or of such remarkable powers. In the end a three years’ truce was concluded, and immediately after a treaty of marriage between the Duke of Rothesay, the Scotch King’s eldest son, and Richard’s niece, Anne de la Pole, daughter of the Duke of Suffolk. On this betrothal the lady, according to the fashion of the times, began to be called Duchess of Rothesay. This match, however, never took effect. On the death of King Richard it was broken off, and Anne de la Pole retired for the rest of her days to the monastery of Sion. The King, who had deemed Nottingham Castle a convenient spot for his headquarters, remained after the reception of the Scotch ambassadors. In October he wrote a letter to his Irish subjects, telling them of the actual date of the commencement of his reign. A copy is preserved in the public records of Ireland, and it concludes thus: ‘Given under our signet at our castell of Nottingham the xii day of October the second yere of oure reign.’

It was not until November 9 that the King left his favourite abode. On that day he set out for London, where he was received with great pomp by the citizens and their representatives. He remained until May, and thence returned via Kenilworth and Coventry to Nottingham, arriving at the castle June 22. One great reason for the preference which the King gave to Nottingham was undoubtedly its central situation. He was almost equally distant from any point at which an invading party might land, and this, with the prospect of invasion staring him in the face, was justly regarded as a matter of considerable importance. On the day of his arrival at the castle his Grace sent letters to the commissioners of array in every county, directing them to at once muster their lieges, as he had received certain information that ‘rebels and traitors associate with our ancient enemies in France,’ intended hastily to invade the realm.

Early in July information was conveyed to his Grace that Richmond had a fleet at the mouth of the Seine ready to set sail. On the 24th of that month the King wrote to his Chancellor to send him the Great Seal by Thomas Barowe, the Master of the Rolls (previously rector of Olney, Bucks). Barowe hastened with it to Nottingham, where he delivered it on August I, 1485, in the oratory at the chapel of Nottingham Castle in the presence of the Archbishop of York and others. The King immediately re-delivered it to Barowe, and appointed him Keeper of the Seal until further orders. On August 7 the Earl of Richmond landed at Milford Haven. Without a moment’s delay Richard prepared himself for the inevitable conflict, and the standard of war was raised on the pinnacle of the new tower. Meanwhile Richmond had progressed as far as Shrewsbury, gathering strength as he advanced, and when Richard was ready for action his troops lay at Atherstone. After a council of war in the castle, Richard marshalled his forces, some say in the marketplace, and others state in the meadows, and with an ostentatious parade and a show of great strength marched out of the town for Leicester. Everyone knows the disastrous sequel on the field of Bosworth, and on the fall of Richard Nottingham lost no time in gladly recognising the accession of Henry VII. Le roi est mart, vive le roi !

Henry VII. visited Nottingham in his progress through the kingdom in 1486, and was met by the Mayor and his brethren in scarlet gowns, and on horseback, about a mile from the town. His Majesty came again in 1504, and seems to have enjoyed himself at a banquet, towards which he contributed the meat and the town the wine and seasoning. We quote from the records the following interesting item: ‘Payd for wyne at the eyting of the venesson that the King gaffe, and for flour and peper and dressing and howesrome and fewell as it was showed by a bill vijs.’ It is not surprising to find that after all this pleasant interchange of courtesies a new charter was granted to the borough in 1505.